11 Creative Lessons from Brian Eno

The legendary composer on the creative process, importance of deadlines, problem with software in arts and what is art actually for?

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we will talk about creative lessons from music legend Brian Eno.

Also this week:

OpenAI fires Sam Altman

Amazon’s UX problem

…and them wild memes (including 13th century stuff)

In the mid-1990s, musician and composer Brian Eno — who has worked with U2 and David Bowie — created the iconic Windows 95 startup sound.

Instead of linking to the audio, I’ll show the Window 95 logos. You should be able to hear the sound by reaching deep into your memory and remembering those glorious days of re-booting your Dell desktop before playing Doom.

The brief that Microsoft gave to Eno for the sound was kind of absurd: “A piece of music that is inspiring, universal, futuristic, sentimental, emotional…and only 3.25 seconds long.”

Eno told SF Gate that it was “like making a tiny little jewel” and created 84 versions of the sound.

Microsoft paid him $35k for the work, which is an incredible deal considering it has probably been heard by over a billion people. But the real benefit for Eno was that the Windows 95 sound unlocked a creative block he had with his other music projects.

“I got completely into this world of tiny, tiny little pieces of music,” Eno explained in the SF Gate interview. “I was so sensitive to microseconds at the end of this that it really broke a logjam in my own work. Then when I'd finished that and I went back to working with pieces that were like three minutes long, it seemed like oceans of time.”

The Windows 95 startup sound is a great story of how constraints breed creativity.

By all means, share this story with your friends.

But if you do, I have one warning: I posted this story on X and actually got roasted by a few users. Why? The qualifier I added to the opening sentence (“worked with David Bowie and U2”) triggered Eno fans, who were really annoyed that I wasn’t giving enough respect to the 75-year old musical legend. Eno coined the term “ambient music” and has created some of the most notable works in that genre. Meanwhile, the artists I mention — along with others like Talking Heads, Coldplay and David Byrne — were “lucky to work with Eno” and not the other way around.

I knew of Eno’s work but clearly did not know enough.

Well, I’m here to get yelled at and learn. So, I queued up 10+ hours of Eno’s interviews and — got dang — all this guy does is spit hot fire about the purpose of art and the creative process.

Here are 11 of Eno’s ideas:

What is art actually for?

How to stay in creative mode

Music and the nervous system

Control vs. surrender

Scenius: group genius

Software gives too many options

Beginnings are easy, endings are hard

The importance of deadlines

Rawness vs. polish

The anchor of success

“Don’t get a job”

My favorite Eno song

What is art actually for?

Eno says that “art is everything you don’t have to do”.

Here is a thought experiment to explain that quote.

Think of a screwdriver. Humans created the tool to serve the functional goal of constructing things (to keep peace in my marriage, I’ve outsourced a lot of “constructing things” to Task Rabbit).

That functional purpose is represented by the tip, which is identical across all screwdrivers for a specific screw or drill bit.

You have to make the tip that way for it to work.

On the other hand, the screwdriver handle doesn't need to be exactly the same in terms of appearance, feel, or design. This is what makes the handle a form of "art". While comfort may be a factor, it ultimately comes down to a stylistic choice for your preferred handle.

This framework applies to any everyday object. Consider your coffee mug, car, clothes, desk chair, or laptop.

Each object has a necessary function, while everything else is considered "art." For example, a coffee mug obviously has to hold liquid, but the handle can have various designs that cater to different aesthetic preferences.

The idea that anything “you don’t have to do” is “art” is a universal. It permeates everyday life across cultures and time. It clearly serves a purpose. It gives us comfort. It is a way to express ourselves. It is a form of communication. It helps us bond. These are all crucial aspects of the human experience. If “art” didn’t achieve any of these goals, our species wouldn’t have been making such stylistic decisions for thousands of years.

One salient example Eno highlights is haircuts. If we only cared about the function of hair, most people would have a similar appearance (like a buzzcut in the military). But the large majority of people — across all cultures — care about the “art” of their hair. The things you “don’t have to do” with your hair.

Eno believes society undervalues “art” and has been working to create an intellectual framework to explain why it exists. His interest in the topic began when he was a child growing up in Suffolk, England. From a young age, he wondered about the power of certain writings or songs to evoke emotional responses. Or to inspire people to imagine and create new worlds.

We don’t have a language to explain the purpose of art.

Think about the world of science before and after Charles Darwin’s “Origin of Species”. Prior to the book’s publication in 1859, Eno says “there was no single intellectual matrix upon which to fix all of these impressions and ideas…there was no way of organizing all of that information.”

While you may agree or disagree with his theory, Darwin’s findings provided a way to understand and talk about the hierarchy of life on Earth.

We are still in the pre-Darwin world as it relates to “art”. There is no properly understood language for why we have it in society. And we can’t properly value it until we do.

How to stay in creative mode

Eno has worked in three parallel art forms for decades: pop music, serious composing and visual arts.

In the mid-1970s, he developed a system called Oblique Strategies to help people maintain a creative state.

Let me walk through the problem that Eno was trying to solve.

He believes that enthusiasm and alertness are key components of creativity. However, he noticed that artists tend to struggle with maintaining these qualities when working under pressure. And this happened a lot. Why? Because it cost so much to rent a studio that musicians were incentivized to just re-create their previous work instead of taking the risk of exploring new — but uncertain— sounds.

Doing the same thing over and over reduces excitement and enthusiasm.

Oblique Strategies is a deck of over 100 cards with different prompts designed to get people back into a creative mindset (instead of letting stress, boredom or tiredness overwhelm).

The cards — which you can buy here — have been used by people in all fields for decades to “break mental habits” and challenge the mind.

Prompts include:

Emphasize differences

Just carry on

Try faking it

How would you have done it?

These appear to be micro-versions of the Microsoft story (pun intended) in which Eno broke out of a creative rut by tackling different challenges (e.g. the 3.25 second Windows 95 jingle).

Music and the nervous system

The human nervous system is made up of two parts, that play opposite roles:

The sympathetic nervous system activates our fight or flight mode in response to perceived danger.

The parasympathetic nervous system restores the body to a state of calm.

Music and sounds can activate either system.

When you want to get pumped for the gym, throw on that Rocky III soundtrack. When you want to relax at the end of the day, listen to a 60-minute YouTube video of ringing gong sounds.

Eno's ambient music work addresses the parasympathetic system. He has designed calming atmospheric sounds for public spaces such as hospitals, grocery stores, and airports.

In fact, the most-viewed Eno ambient track on YouTube is called “Ambient 1: Music for Airports”.

Released in 1978, the album “consists of four compositions created by layering tape loops of differing lengths” and “though it is not the earliest entry in the genre, it was the first album ever to be explicitly created under the label ‘ambient music’".

The first comment on the video is fascinating:

“Eno sought to create music that could be interrupted at any time (for flight announcements and such) without in any way harming the music. Also, since the music would probably be talked over, none of the instruments or frequencies matched the sound of the average human voice so there would be no need to compete for sonic space. He also noticed that most music played in airports was annoyingly cheerful, probably in hopes of assuaging passengers' fear of flying.

[Eno described the old airport music] as "you're not going to die, la la la!" He found this pretty shallow and tried to create a counter-narrative with this music of "you might die, but cosmically speaking, that won't matter.”

Another thought that Eno has on the sympathetic vs. parasympathetic response is that people living in urban environments are in a constant state of “flight or fight”.

For balance — and to engage the parasympathetic nervous system — it is important to bring the nervous system into a state of calm and ambient music is one way to help achieve that.

Meditation is another way. So is walking in nature, which also happens to be the subject of my favourite Wikipedia entry ever: “Shinrin-yoku” aka “Forest Bathing”.

Control vs. Surrender

Here is another thought experiment.

Imagine you are surfing. There are periods of control and surrender.

Control: You paddle past the breakers to find a good place to catch a wave.

Surrender: When the right wave comes, you let it take you.

Eno uses this analogy to explain everyday life. In today’s society, it is easy to understand the concept of “taking control” but more difficult to “surrender” (not in the negative connotation, but just going with the flow).

In Eno’s words:

What I mean by surrender is a sort of active choice not to take control. So it's an active choice to be part of the flow of something. For instance, I think we certainly enjoy surrender situations and the ones we typically enjoy are sex, drugs, art, and religion. Those are all surrender situations.

I'd say they're all situations where you stop, where you deliberately let go of some control to be carried along on something. And for me, the perfect analogy is surfing, which I don't do by the way, but I have watched with some interest. I don't do anything really. I just watch documentaries about it and then make theories. So what you see when you watch someone surfing is they take control momentarily to situate themselves on a wave and then they surrender. They're carried along by it, and then they take control again and then they surrender. Now, I think that's a very good analogy of what we do throughout our lives.

We are constantly moving between the control phase and the surrender phase. The only thing is that we tend to dignify the control side of the spectrum…more than the surrender phase. We tend to dignify people who are good at control as well. We think those are the masters of the universe, and we don't particularly pay attention to people who are good at surrender.

But if you think that the control part of our being is really quite recently evolved. If you think of the 99.8% of human existence until 2000 years ago, most of the time one was surrendering gracefully and trying to stay afloat, trying to use what little bit of control you had in a mostly surrendering environment. So we are good at surrendering. We evolved to do it, and I think we like doing it.

Surrendering — in the sense of “going with the flow” — is just as much of a skill as being in control.

Scenius: group genius

This might be Eno’s most popular idea.

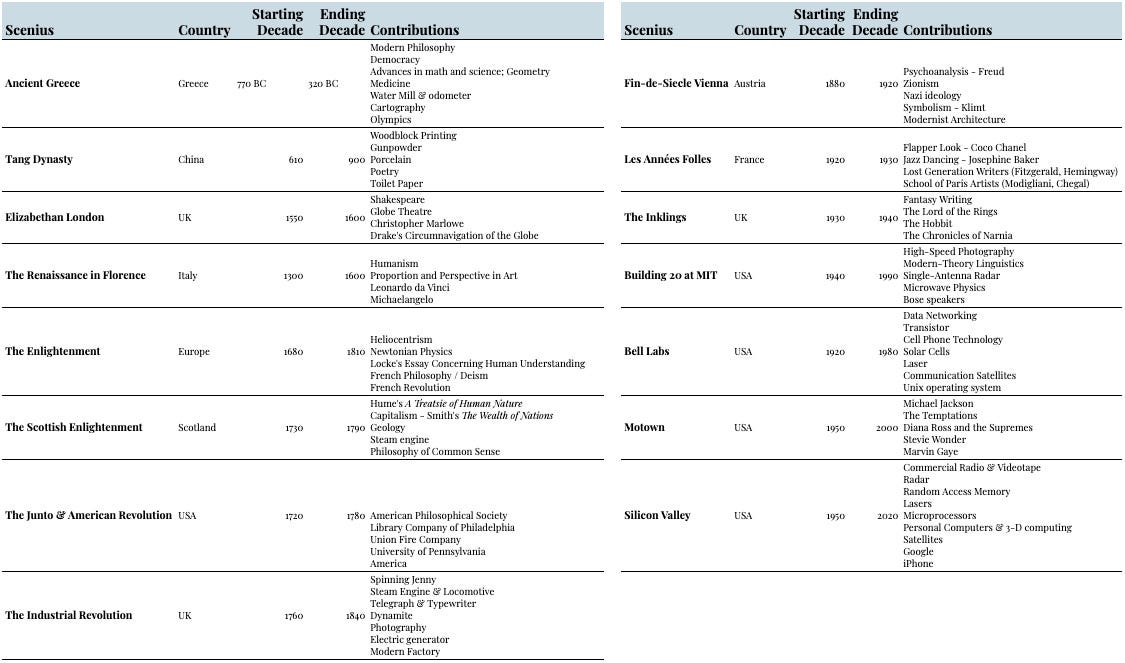

Scenius is a great portmanteau of “scene” and “genius” and it stands for “the intelligence and intuition of a whole cultural scene…it is the communal form of the concept of the genius… scenius is like genius, only embedded in a scene rather than in a gene”.

Instead of lionizing individual geniuses, it is important to consider the “scene” they operated in and how that environment influenced and inspired their work.

Here is Eno on the etymology of “scenius”:

So this word came about when I went to a painting exhibition at the Barbican about 25 years ago, and it was an exhibition about…my favorite era of painting, which was the early 20th century in Russia [1905 to 1928].

As I said, this was a period that I thought I knew a lot about. I knew a lot of very obscure painters…Of course, I knew who the stars were. Kandinsky being one of the early refugees from that period and then Rodchenko and so on. So, I went to this show and I saw works by about 150 painters I'd never heard of.

This was really a surprise to me because I really thought I knew that period quite well. And the interesting thing about them was that there wasn't a huge distinction of quality. It wasn't like Kandinsky right at the top there and then all these other people. There was actually not much difference in quality between the work of some of the people I'd never heard of and the work of the people that everybody has heard of.

So, I suddenly started to have a different idea of art history. The word genius applies to people like Kandinsky and Mondrian and the big names like Picasso. But actually they don't sort of come out of nowhere. They come out of a whole scene of people who support them in various ways and from whom they grab ideas.

Look at Picasso — at the period that he was living in Paris — and look at what else was going on in Paris at that time. Picasso was a brilliant thief and quite happy to acknowledge it. Like any pop musician is, nobody works in a little cage. They're always grabbing things and repackaging them.

For more on the idea, check out Packy McCormick’s essay “Conjuring Scenius” for the conditions that create a “scene” and a brief overview of some famous ones including Ancient Greece, The Enlightenment, Bell Labs, Motown and Silicon Valley.

Software gives too many options

Eno has no qualms about using technology for music production.

But he notes an interesting downside: technology removes constraints, which — as we discussed with the Windows 95 startup sound — is important for creativity.

Per Eno (bold mine):

Doesn't it strike you as interesting that we are in the second decade of the 21st century and a lot of the most interesting music is still being made by people playing very primitive instruments like electric guitars and drums.

I mean, what is a drum kit? It could be a bunch of old chairs or cans or anything. It's really quite an arbitrary bunch of junk, but why is it that people can still make interesting stuff?

Not only interesting but [also] innovative stuff using those tools, which — in digital terms — are hopelessly limited compared to all the fabulous possibilities of software synths and a program like Logic?

Well, the reason is because it's hopelessly limited. The reason is that you very quickly can understand what you can do with an electric guitar or a violin or a set of drums and you stop looking for more options and you start grappling with it.

The problem with software-based work is that you never know what it does. You can never exhaust what it does. So you can always cover the fact that you haven't got an idea by trying another option. If you have a lot of options, you don't usually have a lot of rapport with the instrument. If you have a few options, your rapport keeps increasing because you understand the options better and better. And this is why people still make good music with crude instruments and simple instruments. Because they understand them better than our software.

Eno shared this thought in 2013.

It holds even more true in the world of generative AI.

Beginnings are easy, endings are hard

This Eno idea combines a few of the previous concepts including the drawbacks of software and control vs. surrender.

The main thrust is that it is so easy to start something new. Tools and ideas are plentiful. But the act of completing a project — which I’m sure all of you can relate to — is so so hard.

Here is Eno spitting more hot fire:

“I always say ‘beginnings are easy, endings are hard’. Beginnings get easier and easier [because] there's so much technological assistance [and] so many ways of getting something started like rhythm machines and chord pattern makers.

There are a lot of ways of getting something pretty respectable going quite early on. To quote Picasso, ‘there's nothing worse than a brilliant beginning’.

[But then there is that] feeling of terror when you've done something that you know is good and you just don't know how not to ruin it. You think everything you try on will make it worse and yet you know it's not finished.”

The fear that Eno explains isn’t some abstract concept.

He has over 2, 800 incomplete works himself.

One method that he has found to try and finish these pieces is to simply play them on random shuffle and “surrender” to a serendipitous moment of creative breakthrough (if it ever does arise).

Maybe a certain song is meant to be finished at a specific time and place:

But I think you should think about this control and surrender thing. That's what I think this question is about. It's about where am I allowing myself to be on this spectrum.

As electronic musicians, a lot of our time is spent in control. That's what it is all about. It's about fiddling with software and code and plugins and what have you. And not a lot of our time is spent listening to what we're doing.

So I have a trick that I use in my studio because I have these 2,800 odd pieces of unreleased music and I have them all stored in iTunes file. And so when I'm cleaning up the studio — which I do quite often — I just have it playing on random shuffle. And so suddenly I hear something and often I can't even remember doing it or I have a very vague memory of it because a lot of these pieces, they're just something I started at half past eight, one evening and then finished at quarter past 10. [Then I] gave some kind of funny name that doesn't describe anything and completely forgot about it.

And then years later on the random shuffle, this thing comes up and I think, ‘wow, I didn't even hear it while I was doing it.’ And I think that often happens. We don't actually hear what we are doing. [While we are] in control mode, we don't go into that other mode [which is the listener mode and surrender mode]. The ‘let it happen to me’ mode. And so I think you should try to find ways of letting that happen to you more often and then you'll find the places where you are getting that feeling. It may all be there already. You just haven't noticed it. That often happens.

I often find pieces and I think ‘this is genius’. Which me did that? Who was the me that did that?

The importance of deadlines

Eno also shared some thoughts on how to apply the “control” mindset to his unfinished catalog of over 2,800 songs.

Specifically, he talks about why deadlines are very important:

[My daughter] was in my studio and she was looking at my archive where I have 2,809 unreleased pieces of music. And she said, ‘dad, how do you actually finish any of these?’

And I said, ‘when there's a deadline.’

And that's really true, but I'll tell you why that's true.

When there's a deadline, there's also a destination, a context, a reason for something. And that's what makes me finish it. Up until that point, it's an experiment. It's sitting on my shelf and I can take it down again as I often do, work on it again, put it back on. [Then I can take it] out two years later and work on it some more.

So everything's in progress until there's a reason to finish it.

Rawness vs. polish

Technology is great for optimizing art. But this process just makes everything look or sound the same.

Increasingly, the work that stand out will be more raw and incomplete (because — by definition — new ideas haven’t been optimized because…they are new).

[On one end, you have] auto-tune that perfectly puts music into tune…which is sort of flawless and faultless. [In contrast, the other side] is clumsy, awkward, crude and unfinished things that we all actually like in the right context.

The reason we like the Velvet Underground is not for their gloss. It's for their roughness. For the feeling we have that this was…just breaking out and they didn't know how to make it better. Because when something is new, you don't know how to make it better. In fact, you don't even consider that you could make it better.

You just think, ‘Jesus, this is amazing.’

I think the newness is such a big thrill that you don't care about [a polished product].

Eno also cautions against introducing polish too early in the process.

He calls it “premature sheen”. You can basically take any raw music and make it “sound good” right away. But if you do that too early, you’re short-circuiting the exploration process of what you are actually trying to create:

You can make anything look really good really quickly if you've got the right [software tools]. Suddenly, you think ‘wow I've got something here.’ But you've gotten away from the actual original soul and purpose of [the work].

It's now very easy in studios to get premature sheen and it makes you think ‘wow, look it's nearly done’ [but it’s actually a long way from being done].

The anchor of success

Never be satisfied with your previous work.

Don’t get pigeon-holed on previous successes.

If you do, you won’t have the creative space to explore new ideas and you’ll just be re-hashing old work:

There's a tendency in the world for people — if you've done something and it's been successful — to want you to always be doing that same thing again and again.

I can completely understand it and I'm not blaming anyone for it.

But it creates a sort of anchorage that I don't particularly enjoy.

People are always congratulating me for the album I made 20 years ago…and it sort of introduces two thoughts:

Was it better? Have I deteriorated since then?

Do I have any better ideas?

[The thrill is to go to the edge of what you can do instead of doing the same work over and over]. That’s the thrill of working for me. If I feel the anchorage too much and the sense of looking backwards, it just holds me back.

“Don’t get a job”

Eno spent fives years in art school and has been quite vocal on how the education system — and the pipeline to professional life — stifles creativity.

A viral clip of Eno has circulated, in which he says, "Don't get a job." What he is trying to convey is to not limit yourself to one specific career path that may prevent you from exploring other options:

I often get asked to come and talk at art schools, and I rarely get asked back, because the first thing I always say is, ‘I'm here to persuade you not to have a job.’ The professors always look a bit nervous, since they often consider their task is to somehow smooth you into a job. My first message to people is to try not to get a job. That doesn't mean try not to do anything. It means try to leave yourself in a position to where you do the things you want to do with your time, and where you take maximum advantage of whatever your possibilities are.

My favourite Eno song

Well, other than the Windows 95 Startup jingle.

I'm going to get roasted by Eno fans for not choosing an Eno-specific song, but Eno produced U2's "With or Without You" which is an all-time favorite for me:

Other Eno-produced bangers that I enjoy — because I’m a sucker for popular tunes and my friends call my “Top 40 Phan” — are “Beautiful Day” (U2), “One” (U2), “Viva La Vida” (Coldplay) and “Paradise” (Coldplay).

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email.

If you press this blue button below, you can save hours of work with AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Links and Memes

OpenAI fires Sam Altman: Absolute shocker in the tech world. In an apparent board coup, the OpenAI CEO and co-founder was pushed out. Fellow co-founder and President Greg Brockman also resigned.

The reason: it looks like OpenAI’s chief researcher — and another co-founder — Ilya Sutskeyver had concerns over safety and speed of development.

Here is the joint message from Altman and Brockman:

Sam and I are shocked and saddened by what the board did today.

Let us first say thank you to all the incredible people who we have worked with at OpenAI, our customers, our investors, and all of those who have been reaching out.

We too are still trying to figure out exactly what happened.

Here is what we know:

Last night, Sam got a text from Ilya asking to talk at noon Friday. Sam joined a Google Meet and the whole board, except Greg, was there. Ilya told Sam he was being fired and that the news was going out very soon.

At 12:19pm, Greg got a text from Ilya asking for a quick call. At 12:23pm, Ilya sent a Google Meet link. Greg was told that he was being removed from the board (but was vital to the company and would retain his role) and that Sam had been fired. Around the same time, OpenAI published a blog post.

As far as we know, the management team was made aware of this shortly after, other than Mira who found out the night prior. The outpouring of support has been really nice; thank you, but please don’t spend any time being concerned. We will be fine. Greater things coming soon.

Altman — who has no equity in the for-profit arm — added this shortly after Brockman’s post: “if i start going off, the openai board should go after me for the full value of my shares” (translation: things are about to get real).

OpenAI’s mission was founded as a non-profit to create artificial general intelligence (AGI). It created a for-profit arm to raise money and commercial necessities have taken over since the launch of ChatGPT last year. The AI chat app quickly got to 100m users and is on a run rate of $1B+ a year. It looks like the for-profit and non-profit missions were no longer compatible.

The biggest lesson for me: never accept a last-second Google Meet invite.

Now, OpenAI CTO Mira Murati will take the top job. So many questions remain, but here are some other details:

Microsoft has invested $10B+ into OpenAI but didn’t have a board seat and was apparently informed of the firing only minutes before the rest of the world found out. CEO Satya Nadella and team were blindsided but expressed full support for the remaining OpenAI team. I repeat: no board seat!

AI doomers: For those not following AI closely, there are two primary camps. One group wants to race ahead while another wants to be more cautious. The latter group is called AI doomers and it looks like enough OpenAI board-members were sympathetic to that view to oust Altman. Austen Allred writes, “If it was actually a safetyist coup that kicked Sam out: 1) Most great talent will leave; 2) OpenAI will rapidly become irrelevant...$80B company will over time go up in smoke; 3) Really excited to watch the race to replace it; and 4) That is just an impossibly stupid decision.”

How are AI startups affected? Box CEO Aaron Levie writes “This is not your standard startup leadership shakeup. 10,000’s of startups are building on OpenAI, and have assumed a certain degree of technical velocity and commercial stability. This instantly changes the structure of the industry.”

Steve Jobs parallel…but even crazier: Jobs was fired by Apple’s board in 1985 before returning 12 years later. People are bringing up this example but author Ashlee Vance makes a good point, “This is like Apple firing Steve Jobs only they're doing it after the iPhone has become the best selling computer in history.”

My prediction: Altman and Brockman will end up raising a gajillion dollars from Masayoshi Son to build that hardware AI device with Jony Ive like we talked about last week. They'll likely be joined by a bunch of ex-OpenAI folk (a number of other key researches resigned following Brockman/Altman news).

Anyways, way more news to come but enjoys these posts while we wait:

***

And them other baller links:

Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky went on Lenny’s Podcast for an incredible conversation on design, product and the influence of Apple. One idea I loved was to “add a zero” to any proposal. This increases the ambition by an order of a magnitude (if it’s 10x better, why not 100x better) but actually has a very practical effect: the only way to make such an improvement is to understand the problem set down to the first-principle. Check it out here.

Amazon’s UX/UI: Part of the US government’s anti-trust case against Amazon is that the company uses dark patterns to make it difficult to cancel the Prime subscription. Former Amazon exec Kristi Coulter explains how part of the Prime issue is that Amazon has long treated copywriting and design as “fluffery” compared to engineering and logistics. The lack of focus on design may have lead to dark patterns.

OnlyFans is huge: The Washington Post profiled one of the platform’s biggest creators and numbers for the app — which basically sells soft and hardcore porn — are staggering. There are 3m “creators” and 230m “fans”. Total payouts have exploded from $238m in 2019 to $5.5B in 2022, which was “more than every online influencer in the United States earned from advertisers that year, according to an analysis into the creator economy this spring by Goldman Sachs Research.”

…and them fire tweets / X posts:

Finally, here is one TikTok trend I can get with: “livestreams” that took place during 13th century Medieval Europe.

I’ve been reading your substacks for a couple of months and I just can’t stop it. Every Saturday new things to learn, incredible anecdotes, and important life lessons in super interesting and complete articles. Keep going, great job🙌🏻