8 Lessons from "Curb Your Enthusiasm"

What Larry David's legendary sitcom can teach about creativity and work.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we will talk about creative lessons from Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Also this week:

Apple Vision Pro reviews

Elon's $56B Tesla pay package

…and them fire memes (including Sesame Street)

The 12th season of Curb Your Enthusiasm will premiere this weekend.

Created by and starring Larry David — who also co-created Seinfeld with Jerry Seinfeld — the HBO comedy is responsible for 4 of the 10 times that I’ve laughed the hardest in my life.

I will link to my favourite Curb gags at the end of this piece. But, first, I want to talk about lessons the show offers on work and creativity.

Two pieces on the making of the show are particularly insightful:

The Origins podcast: A 5-part series on Curb created by James Andrew Miller in 2017. Miller has written some of the best oral histories on the media industry including books about SNL, ESPN, HBO and CAA. His podcast on Curb includes interviews with dozens of cast members and creatives involved in the project.

New Yorker profile: Written by James Caplan in 2004, the article is titled “Angry Middle-Aged Man” and details Larry’s transition from Seinfeld (he left at the end of Season 7 in 1996 and Jerry carried on for two more seasons) to Curb Your Enthusiasm (the show started as an hour-long special in 1999).

Miller refers to Curb as a comedy laboratory and here are some lessons from the show's 25-year run:

Develop Your Own Taste

Non-Obvious Ideas Take a Long Time to Win

Structure and Constraints Breed Creativity

Listen and Observe

Creativity Requires Different Speeds

The Best Want to Work with The Best

Getting Full Creative Control

Create Your Own Luck

Develop Your Own Taste

Larry David was born in 1947 in Brooklyn, New York.

The man who would go on to create two of the greatest sitcoms ever had a slow start.

In interviews, Larry frequently brings up the fact that his sense of humor didn’t develop until he went to college. But once he caught the stand-up comedy bug, Larry knew it was his calling. While his mother wanted him to be a mailman, Larry spent his 20s and 30s struggling financially while trying to make it in comedy.

One reason Larry could not break through: he doggedly pursued his own taste and did not care what the audience wanted to hear (or if they got offended).

“Larry's early stand-up routines were the opposite of what many comics do,” Miller says in the first episode of the Origins series. “They get on stage looking to make people happy and in return are beloved. But Larry wasn't trying even to be liked. He wasn't seeking the crowd's approval and was far from pandering. He was telling them what he thought was funny and — if they liked it — fine. If not, well too bad.”

In the early 1980s, stand-up comedy was dominated by acts who did “commercialized” or “television-suitable” material. Why? Because the holy grail for any stand-up was to get a network TV deal and that meant a lot of comedians stuck to fairly PG jokes.

“[Larry’s] material was uncompromisingly to his own taste, filled with wild tirades about apparent trivialities,” James Caplan writes in the New Yorker profile.

Larry was called a “comic’s comic” for his approach. Entering his 40s and unwilling to change, he accepted the reality that he would likely only ever have a cult following.

Ultimately, Larry’s commitment to his own taste paid off. When Jerry Seinfeld — who had known Larry for a decade from the comedy scene — asked him to co-create Seinfeld in 1988, TV audiences were ready for something different.

Bucking normal TV conventions of the time, the show was famously “about nothing” and the characters — Jerry Seinfeld, Elaine Benes, Cosmo Kramer and George Constanza (who was based on Larry) — were often unlikable. Seinfeld’s plots tied in multiple storylines and episodes often ended with the protagonists taking Ls. It was a new type of show based on Larry’s and Jerry’s unique observational humor.

After leaving Seinfeld in 1996 with a platinum comedic reputation and that NBC money, Larry leaned even more into his own personality for his next project: Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Most notably, Larry was no longer only a writer and show-runner behind-the-scenes. He would now be the main character of Curb, playing an exaggerated version of himself (aka a highly successful TV comedy creator with weird quirks and who often finds himself in cringe-worthy situations).

Jerry and Larry — who are both billionaires thanks to those sweet sweet Seinfeld syndication checks — are clear outliers. However, their success came from staying true to their unique comedy instead of copying what was popular or mainstream.

***

The Long Road for Non-Obvious Ideas

If you have a unique taste, then — by definition — it means that not many other people share that taste.

Long-time comedian Alan Zweibel had this to say about Larry on the Origins podcast:

Any show I've done [throughout my career] — whether people like to admit it or not — there's the [feeling of ‘I could have thought of that’].

Or you watch a show and say ‘gee, I had that same idea. Oh man, why didn't I get to do that first?’.

Larry, there was no competition because he would think of things that if I lived to be a thousand year old [I would never have though of]. I just sat back and enjoyed the ride.

Based on watching his stuff and reading about how other comedians perceive him, it is clear that Larry has an N=1 comedy mind.

There is a generalizable lesson here, though: non-obvious ideas present a great opportunity because there is less competition but the trade-off is that it will take a long time to convince people of the idea's merits.

In which case, be ready for the long haul.

Some quick time math on Larry’s career: he was 41-years old when Jerry Seinfeld approached him to do a TV show. While Larry had some wins on his CV — a year writing for SNL and previous work on a network TV show called Fridays — he was living in rent-subsidized apartments in New York and scraping by. To make ends meet, his odd jobs for the previous two decades included being a bra wholesaler, a store clerk, a limousine driver and a historian.

I know some of you are thinking, “Trung, there are countless people who have had non-obvious ideas that failed.”

That is true and I am aware of survivorship bias. However, Larry’s long road to success with a unique idea has echoes in other industries.

While reading up on Curb, I was reminded of the essay Y Combinator founder Paul Graham wrote about startup ideas:

…the best startup ideas seem at first like bad ideas. I've written about this before: if a good idea were obviously good, someone else would already have done it. So the most successful founders tend to work on ideas that few beside them realize are good. Which is not that far from a description of insanity, till you reach the point where you see results.

To be clear, I am not suggesting you work aimlessly on a new project or company just because it is based on a non-obvious (or bad-sounding) idea. What I am saying is this: actually give a non-obvious (or bad-sounding) idea time to marinate.

A non-obvious idea will take longer to come to fruition (as compared to a derivative of an existing idea or an obvious idea). To emphasize Graham’s point: if it were obvious and good, it would have been done already.

We live in an age when it is so easy to "start something new" — newsletters, e-commerce stores, software apps — that people are willing to walk away from a venture at the first sign of friction. With non-obvious (or bad-sounding) ideas, there will be a lot of friction. Most people will not understand the idea. And when people don't understand an idea, they tend to criticize it and think of all the ways it could fail.

It takes a long time to develop non-obvious ideas, and it also takes a long time for the world to understand them.

One lasting legacy of Larry’s work is the mainstreaming of cringe. On the Origins podcast, he says “People told me after the show started airing that they had to leave the room for some scenes because they were cringing and they couldn’t bear to watch. It was like a horror movie. I had no idea it was having that effect on people. That was a complete surprise to me, and I liked it.”

There were cringe-inducing moments on Seinfeld — usually from George Constanza — but Curb took it to another level. The Ringer’s Katie Baker traces Larry’s cringe influence to countless TV acts since including Arrested Development, The Office, Succession, Nathan Fielder (Nathan for You, The Rehearsal, The Curse), Broad City and Sacha Baron Cohen (Ali G, Borat).

You don't have to grind it out for decades like Larry to find out if your idea will work, but ask yourself, "Have I given it a chance?"

***

Structure and Constraints Breed Creativity

The shorthand rule for scriptwriting is that one page is equal to about one minute of screen time.

For a traditional TV sitcom, the ballpark page count is 25-35 pages with every line of dialogue written out.

Conversely, Curb Your Enthusiasm relies on improv and — for this reason — a typical script for the show is only 6-7 pages with scene outlines but little dialogue.

To create a comedy laboratory, Larry believes that improv conjures up the best laughs. The actors are often not told the full narrative arc and are allowed to flex their real-time comedy chops.

“Would this scene have been better if I had written it?” is something that Larry often asks himself on set. His answer on the Origins podcast: “98% of the time I thought, ‘it was better improvised’ [because with improvising] you can get to place you couldn’t get to [with writing]”.

None of this is to say that Larry doesn’t have a plan. The setup in his head is very detailed. The New Yorker shared this scene outline from Season 3 / Episode 8 (warning: parental advisory for the last sentence):

CHERYL is talking to WANDA and her boyfriend, KRAZEE EYEZ KILLA. They have some interaction with an OLDER BLACK COUPLE, who are Wanda’s parents. During all of this, we keep hearing a popping noise that sounds like a cap-gun going off. We then pan to LARRY and find him stomping on packing bubbles. Cheryl approaches Larry and tells him to cease and desist. Larry starts chatting with Krazee Eyez Killa. Larry asks where he lives, and Krazee Eyez Killa abruptly changes the subject and asks Larry if he likes to eat pussy.

The comedy riffs based on these outlines are legendary but there is a very clear method to the madness as explained by early Curb director Bob Weide:

I think one of the misconceptions about something like Curb is that it was a free-for-all and…the actors would get in front of the camera…and we would just say ‘action’ and people would just improvise the scene.

But that wasn't the way it was at all. Larry David is a writer and a structuralist (a very disciplined structuralist). So, the outlines for Curb were very very specific. There was a sense of exactly where the scene had to go to [nail it]. Certain points had to be made occasionally…lines that had to be said. […]

Because everybody was so skilled, you had this kind of heightened, funniest version of the scene [within four or five takes]. Both Larry and I as writers were very conscious of that structure and maintaining that structure, even though part of the joy of doing something like Curb is the surprise and the discovery of not knowing what's going to happen. [Then you have somebody] coming up with something that is just golden that could never have been written, and that happens just all the time, which was fantastic.

The actors trust Larry to keep track of the show’s stories and narrative arcs. Their job is to mine the biggest laughs based on the scenarios laid out in the script.

The entire approach feels like a comedic version of General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s quote that “plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”

Larry told Bill Simmons on a recent podcast that his only goal every season is to make the “funniest show”. Part of that requires spontaneity because spontaneity creates something new. Doing an easy or obvious joke is anathema to Larry. During the episode, Bill pitched Larry a plot idea revolving around someone ruining the outcome of a sports game that he had recorded and planned to watch later.

“That is too easy of a premise,” Larry said. “You want to think of things that other people might not think of.”

***

Listen and Observe

The improv DNA for Curb Your Enthusiasm requires an acting skill that is less necessary for fully-scripted shows: the ability to listen.

Cheryl Hines is the actress who plays the role of Larry’s wife on the show. In the Origins podcast, she explains the difference between improv and scripted shows:

I spent years doing improv and just being comfortable with the unknown. What you learn as an improviser is if you listen to what your scene partner is saying, you'll have all the answers. As long as you are listening, there is never going to be an issue. For me, I was comfortable in that space.

But I do know a lot of actors who have a hard time with it because it kind of goes against what you learn as an actor in a lot of classes. They teach you that everything is in the script. [They tell you] that all of your answers are in the script because you know what other characters say about you (even the punctuation in your sentences). So it is all there in the script.

You have to let go of [knowing everything in improv]. What you can do as an actress is think about who your character is and your character's attitude and your character's perspective. Because that is really important as you do an improvised show.

Think about the last conversation you had. How much of it was listening? How much of it was waiting for the other person to finish, so that you could cook?

Honestly, I am not a great listener. I catch myself waiting for the other person to finish all the time. As the person is talking, I’m crafting zingers — most of which will fall flat — and trying to find a way to interject. It’s not a great habit.

For all of his singular comedic talents, Larry built his empire on listening and observing.

As explained in The New Yorker profile, Larry has his notebook at the ready:

Like many comedians, Larry David carries a pocket notebook for writing down ideas…The notebook is a ratty brown thing that looks as if it might have cost forty-nine cents at a stationery store. Its pages are covered with David’s illegible scrawl.

“Somebody commits suicide after arguing with wife over a ‘Seinfeld’ episode,” reads one entry. “[A comedy notable] asks me to go out to dinner,” another begins. “Me and Weide meet him and [the notable’s wife].”

When the time comes to begin writing the new season [of Curb], David scans his notebook for possibilities.

“He’ll go through the notebook and find three or four stories and extrapolate them to worst-case,” Weide says. “He starts to weave them together.”

With other comedians, Larry is always listening and happy to give his seal of approval — a laugh — for anyone that delivers the goods.

Here is another blurb from director Bob Weide:

Larry is just famous for breaking up. I mean, there are times that we went over schedule during any given day just because we had to make time for Larry to control himself and maintain himself, and it was sometimes really difficult […]

As specific a comic vision as he has — and as sure of himself as he is — [he's actually] a very good collaborator and he is very open to input. [Of course, as] a performer and a comedian…he is full of self-doubt too. So, he's always worried about whether something works or not. [He] is very covetous of your input in the process.

Larry is a comedic god.

However, that doesn’t mean he is the only one with the perfect line or joke.

As long as the person saying it is not a corporate suit — as we will discuss later — Larry is listening and observing.

***

Creativity Requires Different Speeds

Rick Rubin — a patron saint for the SatPost newsletter — hosted John Mayer on his podcast last year. The two spoke about how different steps of the creative process happen at different speeds.

When Rubin is working through a new idea, he never rushes it until it is ready (he lets an idea develop at its own pace, even if it takes years). But when it becomes clear that he and his collaborators have “cracked the code” of a song, it is time to buckle down and do whatever it takes to finish the project. Once the spark hits, Rubin rides the creative momentum to the finish line.

Mayer echoes the idea of letting the creative search process happen organically. But when the vision is clear, it is time to switch on beast mode:

[Cracking the code is the] best feeling…I see young artists sometimes with a hard drive full of minute and a half ideas that were just the spark and they move on to another spark and they move on to another spark and they move on another spark.

And I'm like “[if you crack the code]…you don't leave the room. You put sweatpants on, you're in a hoodie, you're not going out tonight [and you work for the next few days until you’re done].

Why? Because the greatest thing is about to happen to you. And all these songs that I play on stage now represent a night I said ‘Shut it down, we got work to do.’

While Curb Your Enthusiasm has been running for 25 years, Larry has never rushed the creative process and has taken many multi-year breaks to gather ideas: S1 (2000), S2 (2001), S3 (2002), S4 (2004), S5 (2005), S6 (2007), S7 (2009), S8 (2011), S9 (2017), S10 (2020), S11 (2021), S12 (2024).

Since season 5 — when Larry started working closely with Jeff Schaffer to oversee the show’s development — the minimum break between seasons has mostly been two years.

The longest break was six years between S8 (2011) and S9 (2017) while S10 (2020) and S11 (2021) had a standard one-year break.

Larry’s comedic batteries are so depleted by the end of a season that he needs time off. When the show is on, Larry works non-stop for at least seven straight months as a writer, actor and editor.

He literally decides every single frame for the show based on all the different takes (and unlike network TV, every single take of a scene is different). A single frame is 1/30th of a second on air (and the average episode is ~28 minutes).

Here is Weide describing Larry’s editing process:

If it were up to me, I’d spend two to three days editing an episode, then move on. But Larry’s a deconstructionist—he has to look at every frame. It usually takes David two full weeks of rigorous cutting to finish an episode.

This is Larry putting on John Mayer’s proverbial “sweatpants”. For sure, he has the luxury of taking multiple years off because of his past successes. But he earned those past successes based on a creative process of:

searching for new ideas

cracking the code and

shutting it down and getting the job is done

***

The Best Attract the Best

Larry's process and commitment to making the "funniest show" is a draw that keeps the cast coming back, even with the uncertainty between seasons.

For over two decades, Larry has flip-flopped on whether or not he will retire after every season. There is no guarantee when he will come back. And if he does commit, the cast usually has to take a pay-cut (due to Curb's budget staying largely the same while the actors' market rates go up during the show's multi-year breaks).

In the Origins podcast, J.B. Smoove talks about returning for Season 10 after a 3-year breather:

It was just like everything came right back, man. And everyone, all the crew, same crew, all the cast and we all just started flowing again like normal. […]

I think Larry makes it easy for you. I think it's kind of like playing T-ball. He just slow pitches it [or its sitting] on that T and all you got to do is hit it. Just hit the damn ball, man.

Don't overthink it. Just have a good time. Just be a character and for us it works for us. It works for the formula of the show. It really works and you can't help but hit the ball. Larry set you up so well. So coming back was easy, breezy, man. We all got back on our bike and we all started pedaling and it worked.

Larry's ability to slow pitch people is why Curb Your Enthusiasm is one of the most sought-after appearances on TV. The table below is an incomplete roundup of personalities that have passed through the show (short and long stints):

Based on that list, it is a good time to pull up Steve Jobs’ insight about top performers:

"The Mac team was an attempt to build a whole team [of A players]. People said they wouldn't get along, they'd hate working with each other. But I realized that A players like to work with A players, they just didn't like working with C players. At Pixar, it was a whole company of A players. When I got back to Apple, that's what I decided to try to do."

Everyone wants to work with Larry.

***

Getting Full Creative Control

HBO deserves a lot of credit for allowing Curb to be Curb.

The cable network is known for giving its directors and showrunners significant creative freedom, including shows like The Sopranos, The Wire, Deadwood, True Detective, Veep, Oz, Insecure, Game of Thrones, Succession, and many others.

It was very easy for Larry to get full creative control for Curb after creating the most successful network sitcom ever. However, the Origins podcast says there was one instance when an HBO executive offered unsolicited creative advice between seasons 2 and 3. Larry responded by saying, "good luck with that...if you can make a funnier show, then do it without me."

Seriously, good luck with that lol

Larry got his way because he was the “800lb comedic gorilla” but he has always been uncompromising, even when he didn’t have the same influence.

On the aforementioned Bill Simmons podcast, Larry said he quit Seinfeld after writing only 4 episodes because NBC gave him and Jerry notes on the show. Larry told the exec “no, we are not doing one [of your suggestions]” and anytime the network wanted to change the show, he threatened to walk away.

“My hand would not obey the command from my brain to write what the [execs wanted me to]”, Larry said on the NBC situation. “All I had to do was say ‘no’. I wasn’t married or anything. I didn’t have kids. I only had to answer to myself. I wasn’t risking anything and I had no problem going back to New York [to do stand-up].”

The advice he gives young up-and-coming writers is to “stay single” if they truly want creative control on their projects. Obviously, this is much more practical for people in their early 20s (even though Larry stretched it out himself until he was in his 40s).

Larry’s career offers the barbell of examples on keeping creative control:

During Seinfeld, he had few other commitments and could walk away

During Curb, he was a comedic legend and could call his shot

Here’s how the barbell looks in the business world. Option 1 is a single startup founder who eats ramen and sleeps on couches to stretch the runway. Option 2 is scoring a first win and having the financial means to have more control on the next venture (e.g. Reed Hasting sold Pure Software for $750m before launching Netflix or Elon made $180m from PayPal and poured it into SpaceX and Tesla).

A related topic on creative control is how much external money to accept.

One case study that I’ve written about is Blumhouse Productions, the Hollywood studio that is best-known for creating low-budget horror films with some of the highest ROI in film history:

Paranormal Activity (Box office of $193M / $15k budget = 12,890x return)

The Gallows ($43m / $100k = 430x)

The Purge ($89m / $3m = 30x)

Get Out ($255m / $4.5m = 57x)

Whiplash ($49m / $3.3m = 15x)

Blumhouse is able to take many shots on goal — thus increasing the odds of scoring a hit — by offering a deal for any talent that wants full creative control:

Blumhouse gives a share of the upside and creative freedom (in the form of the director getting the final cut of a film)

The talent must take a pay-cut on their guaranteed salary and keep the shoot under budget (typically $5m or less)

To summarize: talent gets creative control in exchange for taking less guaranteed money. Both sides are making sacrifices but they are also fully aligned on the upside and downside.

The same dynamic of external money vs. control applies to other businesses.

Here’s an oft-told story: a startup founder takes a massive investment from a VC even if the funds weren’t needed. The VC now has significant input on the startup’s strategy and it can completely warp the business. Investors need a return and this potentially means over-hiring, entering new markets and spending like drunken sailors on ads to grow.

Another HBO show — Silicon Valley — has a well-known scene on the topic. The show’s protagonist (startup founder Richard) has drinks with another founder and they discuss the perils of raising too much money:

Richard: What if you had asked for less (money)?

Founder 2: Like you mean negotiating them down? Can you even do that?

Richard: Yea, why not?

Founder 2: I suppose you could argue that it would [have been] easier to hit more realistic benchmarks and reach cash-flow breakeven. Then, we wouldn’t have faced that down round. And we wouldn’t have had to settle for an acquisition.

Richard: Yeah.

Founder 2: All that money, f**ked me. We could have done a legit Series B and I would still be CEO. I’d have my job [and] my kick-ass house. I’d probably still have my girlfriend.

Richard: Well…

Founder 2 (puts his face in his hand): F******************K!!!!!!!!!!!!

Creative control requires sacrifice in time, money or lifestyle. It’s not easy and it’s not meant for everyone, but it is possible.

***

Create Your Own Luck

As the cliche goes, “luck is when preparation meets opportunity”.

These types of stories happen in every industry, but they are especially prominent in entertainment because it is easy to recognize when someone has a breakthrough song, book, film, or acting performance.

Curb Your Enthusiasm has a few great examples:

Cheryl Hines: When Larry & Co. were auditioning actresses for his on-screen wife, they were looking for an unknown. If his on-screen wife was too famous, it wouldn’t be believable. Hines had spent years at the Groundlings Theater Company, which had trained comedy icons such as Tina Fey, Amy Poehler and Will Ferrell. Though Hines had the improv skills, she never reached the level of fame that those other names did. However, her Venn diagram — which combined comedic training and lack of exposure — made her the easy pick for Larry’s wife after she crushed the audition.

J.B. Smoove: My favourite character on the show is Leon. Played by Smoove — a stand-up who spent a few years writing on SNL — Leon became Larry’s roommate from Season 6 on. Smoove’s road to the role was pure serendipity. Smoove was in LA for one day for a friend’s funeral. “Curb” was coincidentally auditioning for the role right before his plane out of the city. SNL just let Smoove go as a writer and he was looking for work.

His new agent had a hook up at Curb and set up a read. Smoove explained his strategy on the Origins podcast, “I never walk into an audition as myself. I always walk in there as the character…who I'm portraying so they can see how I walk. How I move. How I say ‘hello’. Everything is under the character as opposed to JB going in the room and then doing the character.”

In character as Leon, he told Larry he might slap him. Smoove had so much swagger that the “Curb” team was confused. But he crushed the audition and had Larry in stitches. Before the audition, the “Curb” writers hadn’t fleshed out the Leon character. But when they saw Smoove, they knew that was “Leon” (he posted a clip of the audition on Facebook).

Hines and Smoove spent years grinding in the comedy game and "lucked" into their roles on Curb. However, anyone who has seen the show knows they deserve it.

Both stories are examples of increasing the surface area for luck.

The variable of luck is only going to get more important as more of the global workforce gets online and AI tools flatten technical and language skills. Why? Because the more people there are chasing a goal means the more people there are with comparable skill sets who are all “qualified”. Consequently, the deciding factor ends up being some form of “luck” (an event out of your control).

So, make yourself a luck magnet.

That means working on your craft. Putting yourself out there. And — if you aren’t finding success or getting “lucky” — having a mindset focussed on moving forward instead of dwelling on the past.

In a 2020 conversation with GQ, Larry was very straightforward about the luck in his career:

“Let's face it, if Seinfeld doesn't come along, what happens to me, really? Here's what I think: I think I'm living in a studio apartment in New York. I think I'm miserable doing it. I think I hate everything and everybody, including myself most of all. I think I'm a guy walking down the street, screaming at people for slights like a bump-into without a sorry, things like that.”

That is pretty cynical and on-brand for Larry.

But his friends don’t seem to think that the success has actually changed him much as a person. Comedian Alan Zweibel says on the Origins podcast:

"If anyone has any doubt that God has a sense of humor, they should just remind themselves that they gave Larry a billion dollars. Okay? Because what's he going to do for angst? He thrives on that, on what's wrong in that thing. Is there any change in him? He goes out of his way not to have changed.

Like I said, he's generous. He's given jobs to people when they've needed it. He's extended himself. He lives in this really nice house and when I go out there, I stay with him. Okay, but you want to know something? I also stayed at that shitty apartment he had on West 43rd Street, so now it's a bigger, nicer place, but it's the same extension of graciousness."

Larry spoke to the New Yorker about why he kept working after Seinfeld: “You need a place to go. A place to go—that’s what my mother always instilled in me. You need a place to go. And you’re worthless unless you have a place to go. So I needed a place to go.”

Of course, Larry got lucky. But he was working his ass off before, during and after the big Seinfeld break.

With or without Jerry, it is pretty clear what Larry would have been doing for the past four decades: still trying to make people laugh with his unique sense of humor and observations on the world.

But I prefer living in the world where Jerry convinced him to do Seinfeld because we got Curb. This means we also got that absurd theme song (it’s called “Frolics” and was inspired by a community bank ad). Most importantly, it means we have hundreds of Larry and Leon scenes (including this 11-minute YouTube mash-up which will bring you to tears).

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email.

If you press this blue button below, you can save hours of work with AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Links and Memes

Apple Vision Pro Reviews: The Apple hype machine was in full effect this week. On Tuesday, top tech journalists dropped their Vision Pro reviews. On Thursday, Tim Cook was featured in a Vanity Fair cover story wearing the headset for the first time (many speculated he hadn’t worn them for months so he couldn’t be meme’d but it all looks like well-orchestrated PR). On Friday, the product shipped.

The top level positive takeaway seems to be that this is the future of computing (and the entertainment features are already unbeatable). The major cons are price, size and weight (all of which will come down). If you want more, check these out:

Vanity Fair: Nick Bilton profiles Cook’s Vision Pro journey. The Apple CEO saw the first version 6-7 years ago. It wasn’t wearable but a contraption of screens, wires and cameras that wrapped around your face and was connected to a supercomputer in another room. Honestly, impressive seeing that V1 turn into this headset. And they also interview James Cameron, who said “my experience was religious…I was skeptical at first. I don’t bow down before the great god of Apple, but I was really, really blown away.”

WSJ: Tech reporter Joanna Stern wore the Vision Pro for 24 hours. The 8-minute review is well worth a watch and the highlight was her using the headset to cook (with recipes and timers hovering over the food).

MKBHD YouTube: Marques Brownlee is the YouTube tech GOAT. His 37-minute review is worth a watch in full. The three details that stood out to me: 1) the Vision Pro’s primary inputs are your eyes and pinching motions; it sounds like using your eyes to do actions is a learning curve because we don’t always look directly at inputs; 2) typing on the virtual keyboard is not good (need a physical bluetooth one) and 3) the Keynote feature where you can practice a slideshow presentation in front of a theatre is very cool.

Two other things to flag is the Vision Pro's Facetime (it’s still in beta and the avatars aren’t quite there yet but reviewers say there is a feeling of presence) and multi-screen NBA League pass (it looks amazing and a killer use case for sports fans).

PS. Some people say Cook looks like Ellen on the Vanity Fair cover but I was more interested in the strategic placement of AirPods, iPhone, Watch, Apple paperweight, the Vision Pro pinching motion and a football helmet from his alma mater Auburn.

***

Some other baller links:

Elon’s $56B pay package was blocked by a Delaware Court judge. In 2018, Tesla’s board created a comp scheme that basically said “if Elon can increase Tesla’s value from $60B to $650B over the next decade and also reach revenue/profitability goals, he would get $50B+ worth of stock”. About 80% of shareholders agreed to the plan (73% if you take out Elon and his brother).

But one shareholder — who only owned 9 shares (NINE!!!) — sued and said that not all shareholders knew about Elon’s close relationship to the board members, thus making the details of the comp plan potentially unfair. The judge agreed and rescinded the package. My takeaway: if you look at coverage from 2018, no one thought Tesla’s targets were possible. Most thought the comp plan was a PR stunt. But he achieved them and, as NYT’s Andrew Ross Sorkin puts it “the comp plan was the most ‘skin in the game’ in history.Meta stock jumped 20% on Friday after the company posted revenue growth of 25% YoY and announced a dividend for the first time (also a $50B share buyback). When Apple knee-capped Meta's ability to track apps, the company fell to $300B in market cap. It's up 4x since then as Meta made signifiant advances in AI, cut a bunch of jobs and figured out the new ad landscape. This news followed Zuckerberg getting grilled by Congress on social media and child safety (the Meta CEO apologized to parents of affected children). My thought is under-15s shouldn't be able to use social apps or only ones with limited functionality. One reasonable step Zuck suggested: have the app store gatekeepers (Apple, Google) be responsible for age verifying users.

23andMe goes from $6B to nearly $0? The Wall Street Journal has a deep-dive on the struggles of buzzy genetics firm founded by Anne Wojcicki (her sister Susan is CEO of YouTube and Anne was married to Sergey Brin from 2007-2015). The main issue: 23andMe hasn’t found a sustainable model (tests are a one-time event that the company is trying to turn into a subscription business with monthly health reports) and suffered a data hack (which dented confidence in the business). Over 14m people have used the DNA kit and there are significant privacy considerations on what will happen to the data if its closes shop.

…and here them lit X posts:

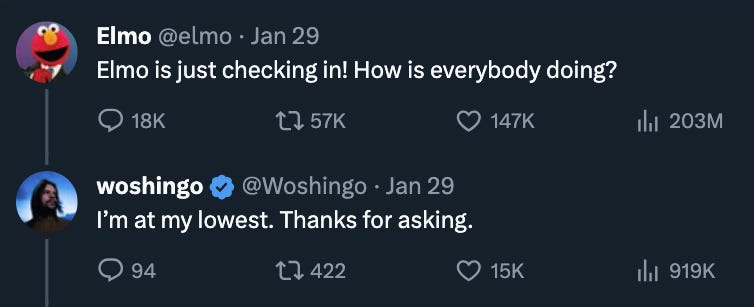

The most-absurd award of the week goes to whoever runs Elmo's social. The Sesame Street character posted on X “Elmo is just checking in! How is everybody doing?” and the post received 200m views. It also got ~100k replies, of which 99.9% were trauma dumping jokes and telling Elmo all of their problems (I think they were jokes…).

But it didn’t end there……after receiving these distressed messages, Elmo posted a follow-up that was re-posted by President Biden with the note that reads “even though it’s hard, you're never alone”.

And, to round out this newsletter, Larry David randomly smacked an Elmo puppet on a morning show (HBO does own Sesame Street, so it might be part of some elaborate PR scheme). I’m still trying to figure out what happened.

This was just a fantastic synergy of ideas. Great read, Trung!

Great stuff, Trung! 💚 🥃