Disney Loves (and Hates) Public Domain

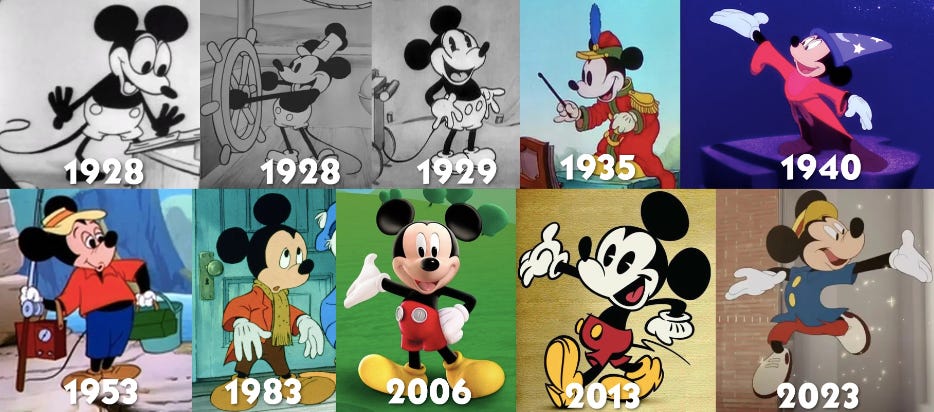

Disney lost copyright on the 1928 "Steamboat Willie" version of Mickey Mouse. It's the culmination of decades in which the company used a ton of public domain but prevented others from doing so.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about Disney losing the copyright on its “Steamboat Willie” version of Mickey Mouse.

Also this week:

A wild alternative calendar

A $750m water bottle company

…and them fire memes (including Pop-Tarts)

UPDATE January 1st, 2025: “Steamboat Willie” entered the Public Domain in 2024. In 2025, a dozen Mickey Mouse animations — including the first speaking parts — entered the Public Domain. Other notable new creative works that entered the Public Domain in 2025 include Tintin, Popeye and major literary works (William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One's Own).

***

January 1st is Public Domain Day, when works — from books to songs to cartoon characters — lose their copyright protection.

The 2024 batch was highly highly anticipated.

Why? Because Disney lost the copyright on Mickey Mouse (specifically, the version that was in the 1928 “Steamboat Willie” short film). And people care about Disney because the entertainment conglomerate has a very contradictory relationship to copyright.

Remember, the purpose of copyright is to make sure that the original creator of a work is able to profit from its commercial use (vs. someone else just taking it and profiting themselves without permission). When the work enters the public domain, it can be used by anyone for personal or commercial use.

This original goal is in tension with the fact that so much of creativity — and innovation — is about building on top of the works of other people.

For decades, the question around copyright has always been: What length of protection is appropriate? Too short and the profit incentive for someone to be creative and invent new things is reduced. Too long and the collective hive mind’s ability to innovate is snuffed out.

Disney is a great lens to address this tension because the company has a foot in two camps:

Voracious user of public domain

Major supporter of copyright extension

Let me explain:

***

Voracious user of public domain

The number of Disney films that are sniped from Public Domain is astounding.

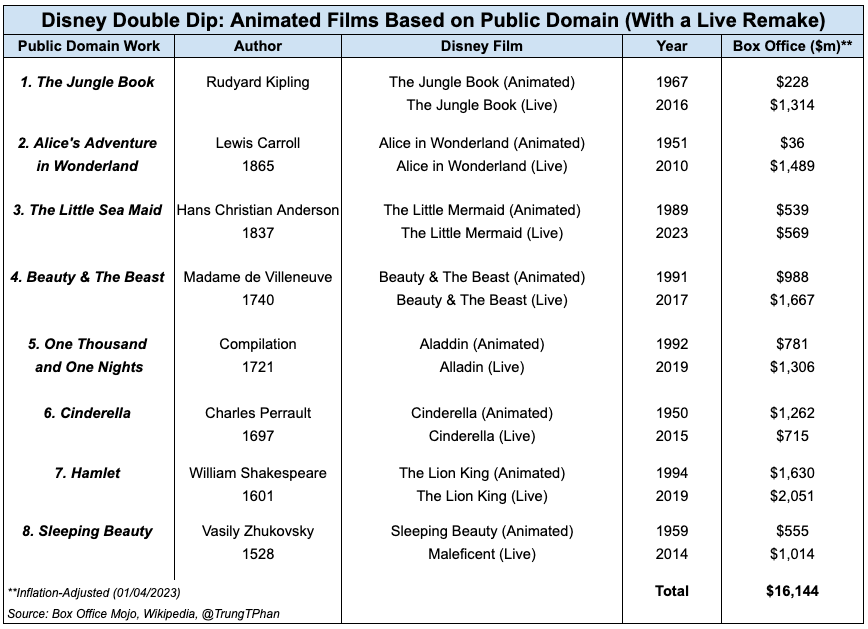

There are at least 50 of them and — for some solid laughs — I made a table of select films in which Disney double-dipped the same Public Domain work: first with an animated version then a live-action remake.

Just 8 of these sources — including Rudyard Kipling (The Jungle Book), Hans Christian Andersen (The Little Sea Maid), Lewis Carroll (Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland) and some little-known writer named Shakespeare (Hamlet) — have accounted for more than $16B at the box office:

This list doesn’t even count other snatched classics like Frozen, Hercules, Pinocchio, Tangled, Tarzan and The Hunchback of Notre Dame among others.

Imagine Hans Christian Andersen in Copenhagen in the 1850s banging out some classic fairy tales. “I hope one day there will be moving images to pair up with these rhyming words,” Hans probably thought while getting buzzed on Danish Snaps he made in his bath tub.

Let me tell you Hans, the moving picture did come. And the corporation that owns moving pictures based on your IP have made $1B+ in ticket sales from these venues called “movie theatres”, where people buy bags of corn that is popped for $50.

These weren’t strip rip-offs, though. The studio obviously sanitized the source material — which are pretty crude in the original readings — for a young mid-20th century audience.

But even then, there is room for literary and creative criticism as famously proffered by J.R.R. Tolkien. The legendary Lord of the Rings creator saw Snow White in 1937 and disliked how Walt infantilized the characters, taking away moral complexity from the stories (contrast the goofy 7 dwarves with the seriousness of Tolkien’s The Hobbit, also released in 1937).

Tolkien worshipped the fairy tale art form and — along with his buddy C.S.Lewis — loved to trash talk Disney’s oversimplified narratives (another take: Tolkien and Lewis were snobby English literary elites looking down on an American artist creating for the masses).

Later in his life, Tolkien refused to let Disney Studio touch his IP.

Here’s a wild passage from Open Culture:

Tolkien described Disney’s work on the whole as “vulgar” and the man himself, in a 1964 letter, as “simply a cheat,” who is “hopelessly corrupted” by profit-seeking (though he admits he is “not innocent of the profit-motive” himself).

[He said], “I recognize his talent, but it has always seemed to me hopelessly corrupted. Though in most of the ‘pictures’ proceeding from his studios there are admirable or charming passages, the effect of all of them is to me disgusting. Some have given me nausea…”

Geez, tell us how you really feel John Ronald Reuel.

In sum: Disney has been sucking on the teet of Public Domain for decades while it is also a…

Massive supporter of copyright extension

In a great 2016 article for Priceonomics, Zachary Crockett — my former colleague at The Hustle — breaks down Disney’s long history with copyright.

The TLDR: In 1927, Walt and his chief animator created a popular cartoon character named Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. The character blew up and then the chief animator took his team to Universal and basically jacked Oswald. In response, Walt created “Steamboat Willie” and was determined to never let someone else control the fate of his animations ventures.

This commitment to protecting IP has manifested in US copyright laws conveniently being extended every single time Disney’s works are about to enter the public domain:

Copyright law in America long predated Mickey Mouse.

The first of these laws, the Copyright Act of 1790, stipulated that creative works were entitled to up to 28 years of protection (14 years, plus an additional “renewal” period of 14 years, supposing the original hadn’t died). This was followed by an 1831 act, which extended the copyright period to a max of 42 years, and a 1909 act, which elongated that period again, to 56 years. As the Art Law Journal clarifies, “very few works actually maintained [these] copyright durations”: only a fraction of those who secured copyrights protected them, or opted to renew them.

Mickey Mouse was brought into the world in 1928, under the 1909 Copyright Act, entitling him to 56 years of protection under the law — no more. In accordance with the law, his copyright was set to expire in 1984.

Disney’s efforts, and those of other multinational corporations with soon-expiring intellectual property, seem to have paid off. In 1976 — just 8 years prior to Mickey’s expiration — Congress completely overhauled U.S. copyright law to conform with European standards. This new law expanded already-published corporate copyrights from 56 years to a maximum of 75 years. All works published prior to 1922 immediately entered the public domain; all works published after 1922 (including Mickey Mouse) were entitled to the full 75 years of protection. Just like that, Mickey Mouse extended his copyright death 19 years — from 1984 to 2003.

Here’s a visualization from Zach on how copyright terms increase (copyright duration on y-axis) every time Mickey Mouse's protection is about to expire (year term begins on x-axis):

The piece d’resistance was Disney lobbying to get the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 passed. The conglomerate’s efforts included 19 of the bill’s 25 sponsors receiving donations from Disney’s CEO Michael Eisner.

For decades, the legislation has derisively been called the Mickey Mouse Protection Act (sick burn!) and extended copyright terms by 20 years:

Individual works: a current span of the author's life plus 70 years

Corporate-held works: either 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation (whichever is shorter)

The simple math — 20 years after 1998 — is also why a bunch of notable works have been lighting up Public Domain Day since 2018 (we’ll get to a few of them later).

Walt died in 1966.

The intent of copyright was to let the original creator(s) and their descendants profit from the work.

That’s a reasonable goal…but for how long?

***

The best way to sum up Disney’s complex history with public domain is something I say to my son probably once a week: “Do as I say, not as I do”.

I earlier noted Disney’s $16B in box office from just 8 public domain works.

That is only ticket sales. If we include everything else from the Disney Money Machine — merchandise, theme parks, home video, linear, DVD sales, streaming and the $50 Mickey-shaped misting fan I bought from Disneyland — that cumulative figure is multiples more. Is it $50B? Is it $100B? All I know is that it is a lot and Han Christian Anderson saw exactly zero of it.

Further, the loss of copyright on “Steamboat Willie” is not a free for all. Duke Law School has a deep dive on the public domain implications and I’ll flag two points:

Disney has many Mickey copyrights: Over the years, Disney has made (often minor) changes to the Mickey Mouse character and was granted a new copyright. Any Mickey iteration after 1928 still has copyright protection.

Trademark still in place: Copyrights cover “creative works and prevent people from copying and adapting them without permission, with the goal of providing economic incentives to create and distribute cultural material”. Trademarks cover “words, logos, images, and other signifiers that serve as brands identifying the source of a product”, which means you can’t sell a Mickey remix with a suggestion that Disney is behind it. Trademarks have no expiration and Disney has spent the past few decades confusing the hell out of my brain (the company’s logo has integrated Mikey Mouse ears, which increases the surface area for potential trademark violations).

Even with these legal protections in place, Disney lawyers have filed fewer copyright lawsuits in recent years. Why? Because content wars have moved to the digital sphere and piracy is the new bugbear.

"Studios have become more concerned with online piracy, which they typically don’t fight in court," writes Variety's Gene Maddaus. "Instead, under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), studios submit takedown notices — millions of them — to online platforms."

What do I think about copyright?

I like what Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig laid out in his iconic Ted Talk titled “Laws That Choke Creativity”. It’s from 2007 but the main points are still relevant:

Read / Write vs. Read Only: Digital tools allow anyone to be a creator. We should foster environments where creativity flourishes and this will often involve remixing previous work (read / write). If laws are overly restrictive, only the largest players — ones that can afford to fight legal battles — will produce while everyone else consumes (read only).

Laws need updating: Prior to 1945, a landowner’s property rights included the land below and the sky above. But Lessig notes that this arrangement made no sense after the proliferation of commercial airplanes (imagine trying to get permission from every single landowner — if their property rights extended into the sky — to fly a route between New York and Los Angeles). The laws had to change with the times.

Based on my very non-lawyerly analysis and with the intent to maximize creativity, we should probably go back to a shorter copyright time frame and also standardize across geographies (there are currently different term lengths in different countries).

The goal: people can (reasonably) profit off of their creativity and others can (with appropriate credit) build off previous work.

Another wrench that needs to be addressed is generative AI and copyright. The New York Times (NYT) recently sued OpenAI for training its large language models (LLM) on NYT articles without permission. Mike Masnick at Techdirt thinks NYT has little chance of winning because copyright law is more concerned with outputs (the final product) rather than inputs (what are used in the creation process and often allowable under the fair use doctrine, which allows a humorous form of social commentary and literary criticism in which one work imitates another).

The paper has examples of OpenAI ripping text verbatim but it also looks like the LLM was specifically prompted for these incriminating outputs. Ultimately, NYT will probably walk away with a licensing deal (similar to one that OpenAI struck with German publisher Axel Springer). This outcome takes us to a previous point I made: those best-equipped to fight copyright battles will be large players and not individuals (individual artists have hit OpenAI and Microsoft with class-action suits but it’s not clear if they are winnable and what the renumeration would be).

Either way, the most viral public domain remixes have been pretty underwhelming since 2018 (which is 20 years after the 1998 Mickey Mouse Protection Act).

The lowest hanging fruit has been “let’s turn pubic domain stuff into scary things because it’s the opposite of public perception”:

The Great Gatsby has turned into Great Gatsby Undead (self-published vampire book)

Winnie The Pooh has turned into Winnie The Pooh: Blood & Honey (low-budget horror)

“Steamboat Willie” Micke Mouse has turned into Mickey’s Mouse Trap (another low-budget horror) and INFESTATION 88 (a horror-themed co-op video game starring mutant mice)

More than eight billion people in the world…and this our best effort. C’mon!

The coolest new Mickey Mouse project I saw is called Mouse, a first-person shooter game with the aesthetic of “Steamboat Willie” (it’s still in development with a 2025 release date).

These projects were probably already doable in some capacity under fair use. To wit: South Park, The Simpsons and Family Guy have all done absurd Mickey Mouse riffs in past years.

In the name of creativity, keep the Public Domain remixes coming.

I trust in the collective hive mind to make something great…just make sure you’re riffing on the right version.

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email. If you press this blue button below, you can try AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Meet the International Fixed Calendar (IFC): The world considered adopting it in the 1930s. What’s the difference? The IFC splits the year into 13 months (each with 28 days). Compared to the 12-month Gregorian calendar, IFC is much simpler as explained by The Washington Post:

Calendar is the same every year

Each month has exactly 4 weeks

Every month starts on Sunday and ends on Saturday

Every date of every month is the same day (“16th” is always Monday)

The 13th month was called “Sol”, as the extra month fell between June and July, around summer solstice. You’re probably thinking “28 x 13 = only 364 days” (and “I’m learning way more about calendars than I expected today”).

To address this — and to get to 365 days — the IFC added a one-day world holiday (“Year Day”) between the last Saturday and Sunday of the year. Kodak founder George Eastman was a fan of IFC and used the calendar for Kodak reporting. Eastman even convinced 100+ other companies to do the same.

Kodak kept the IFC from 1928 until 1989, per BBC. Why? Every month had the same number of days (and weekends), making it easier to compare income statements across months and years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the IFC was the brainchild of an accountant (a British dude named Moses Cotsworth).

The IFC was ultimately scrapped.

Religious bodies couldn’t agree on standardizing certain dates (e.g. the one-day world holiday would change which day the Sabbath fell on every year; there was no agreement on Easter). The business community also realized that existing bonds and contracts — using the Gregorian calendar — would be a pain to update.

Days and years follow the logic of the solar system. Months are way more flexible, and that’s how we almost had the IFC.

YouTuber Tom Scott retired his 6.2m follower channel. I love his backstory and rationale. In his farewell video, Tom said he started posted online in 1999 with little success for years. In January 2014 — 10 years to the day of his last video — he started a new YouTube series with one rule: post every Monday at 4pm.

He did and got a huge following but reached a crossroad. Tom was at the point where he could turn his audience into a larger business but didn’t want to be a manager and was also kind of burnt out. So, he decided to just call it. Tom still has other media projects but will stop posting consistent every weekly.

My favourite episode from Tom was about Cloudflare: For encryption, the cybersecurity firm uses a camera to videotape a wall of Lava Lamps. It then turns footage into a “stream of random unpredictable bytes” to make encryption keys for traffic on its network. Wild.

***

Some other links:

Blockbuster Kid’s Show: Financial Times on “How Australia’s ‘Bluey’ conquered children’s entertainment”. My $0.02: the show’s secret is that the storylines are watchable by both parents and kids (conversely, shows like Blippi and CocoMelon melt the adult brain).

Harvard President Claudine Gay resigned: Here is a good piece from the New York Times’ Ross Douthat on how Harvard views itself and the logic of elite reputation management (“Harvard Couldn’t Save Both Claudine Gay and Itself").

Stanley — the $750m water bottle business: Over the past year, I started noticing my mom friends carry around a giant water tumbler with a straw. After the 6th sighting or so, I was thinking “dafuq is going on”. And they all said it was the best thirst-quenching purchase ever. Turns out the 40oz (1.2L) bottle is literally called the Quencher. And it’s made by Stanley, a 110-year old brand that has gone parabolic in the past 4 years: sales 10x from 2019 ($70m) to 2023 ($750m).

Why? CNBC credits a hire from Crocs, who brought the viral internet marketing juice from the world’s ugliest footwear to the water game. It’s worked so far.

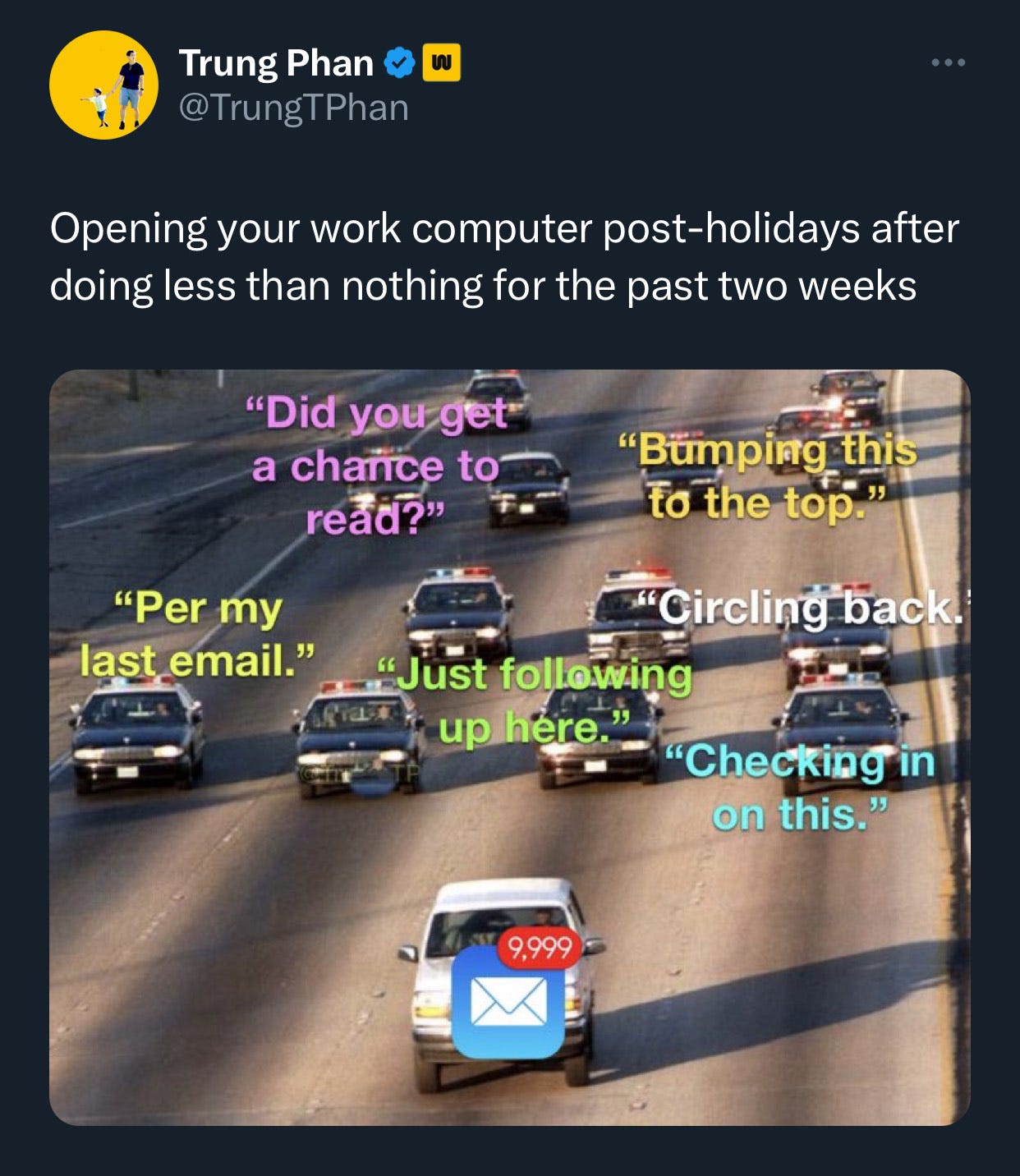

…and them wild X posts:

Finally, College Football held a Pop-Tarts Bowl at the end of 2023. I don’t follow the sport at all but my X timeline started blowing up with memes about a Pop-Tarts mascot. Why? Well, Pop-Tarts had a human-sized mascot that came out of a giant toaster to start the game. Then, the winning team ate a giant pop tart after the game and the mascot — placed into increasingly absurd situations — became a hysterical meme. Here is a whole thread of them including this one that put me into tears: