Gautam Adani’s $140B+ fortune, explained

How the Indian entrepreneur became the world’s 2nd richest person.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we’re talking about Gautam Adani, the Indian entrepreneur who recently became the 2nd richest person in the world with a net worth of $140B+.

UPDATE 11/20/2024 (1pm PT): Adani — the 18th richest person in the world ($115B) as of this update — was charged by New York Feds for paying more than $250m in bribes to Indian government officials to secure solar contracts (and thus obtaining funds from investors in the United States and international lenders ‘on the basis of false and misleading statements’).

You may have seen the headline.

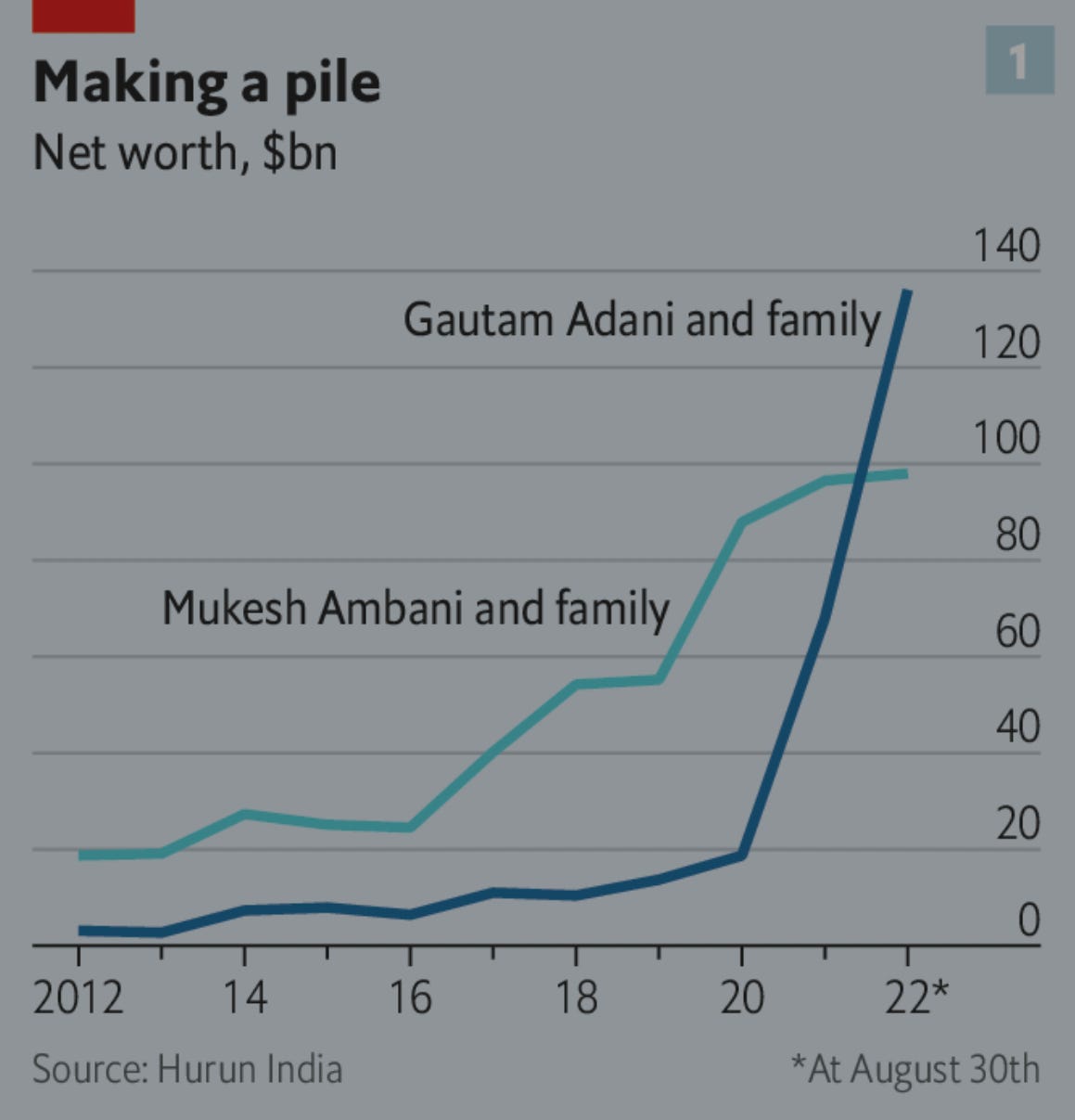

A week ago, Jeff Bezos was unseated as the world’s 2nd richest person. In his place is Gautam Adani. The Indian entrepreneur has seen his net worth jump from $77B at the beginning of the year to $142B.

Of the top 10 richest people, he’s the only one that’s up in 2022. Even wilder, his fortune was $10B right before the pandemic (combined, me and him had a net worth of $10B at the time).

I have to confess: even though my day-to-day job involves tracking business stuff, I had no idea what Adani did up until a few days ago. Embarrassingly, I couldn’t even come up with a funny meme when he overtook Bezos.

So, I did a ton of Googling and share my findings. The source of Adani’s wealth is a $250B+ ports-to-power conglomerate (Adani Group) and there are 4 key ways to understand his empire:

Gujarat and the Mundra Port: Adani hails from Gujarat, the Indian state known for pumping out entrepreneurs (fun fact: ~1/3rd of US motels are run by Gujaratis). In the late 1990s, he founded what is now India’s largest port (Mundra).

Connection to Prime Minister Narendra Modi: Adani’s business empire flourished in the 2000s, a period when the current Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was Chief Minister of Gujarat. Many critics say Adani’s rise is owed more to government connections than his entrepreneurial chops.

Creating an energy empire: Adani turned the success of his core ports business into a sprawling empire with interests in all parts of the economy. However, energy is the main engine — coal accounts for the majority of the Group’s ~$30B in revenue (meanwhile, Adani plans to spend $70B by 2030 for a green energy transition).

Lots of debt: Adani is a huge risk taker and expanded operations by using a lot of debt (some say his close government connections allow for particularly preferential loan arrangements).

Let’s jump into the Adani story.

(PS. The first two sections are heavily informed by James Crabtree’s must-read book The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age)

Gujarat and the Mundra Port

For the past two decades, Adani mostly took a backseat to another Gujarati tycoon: Mukesh Ambani, the head of Reliance Industries, a multi-generation concern that built a $200B+ conglomerate starting with polyester before moving into petrochemicals and — in the past 10 years — retail and telecoms.

While Adani leapfrogged everyone on the Billy list, Ambani remains the 9th richest person in the world with a net worth of $85B.

As alluded to in the subtitle of Crabtree’s book, the pair can be thought of as India’s version of America’s “Gilded Age” titans at the end of the 19th century: Andrew Carnegie and Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Ambani and Adani tower over India’s business landscape and the country has been dubbed the “AA” economy (combined, me Adani and Ambani are called the “AA” economy). Per The Economist, the combined sales for Adani Group and Reliance make up 4% of the country’s GDP and the pair are responsible for 25% of the country’s non-financial firm capital spending (on a related note: India has a ridiculously lopsided wealth distribution, where the top 1% owns more than 4x the bottom 70%).

It’s no coincidence that both entrepreneurs have roots in Gujarat: India’s western-most state has the country’s longest coastline (1,600km along the Arabian Sea) and has been a trading hub for centuries. Within the state, Adani operates India’s largest port (Mundra), which is 50km across the Gulf of Kutch from the world’s largest petrochemical refinery operated by Ambani (Jamnagar).

Adani was born in 1962. He grew up in a family of 8 and — while 80% of India is Hindu — the middle-class Adani family practiced Jainism, which focusses on compassion, self-discipline and asceticism. According to Crabtree, Adani is “a college dropout” who “began his career in Mumbai’s diamond markets before returning to Gujarat to work in a small plastics factory run by one of his brothers.”

In 1988, Adani launched a commodities trading firm called Adani Enterprises. He started the trading firm because the government restricted supply — by setting quotas — on raw materials he needed for his factory.

The catalyst for the trading business is a running theme in Adani’s entrepreneurial career: India’s restrictive policies or lack of infrastructure forced Adani to create his own solution.

From the country’s Independence in 1947 until 1990, India was under a regime known as the “License Raj”, a period of heavy state interference in the economy. Private businesses had to satisfy dozens of government agencies to operate. The arrangement — including regulations, licenses and quotes — was a bureaucratic nightmare and easy lever for corruption.

Following an economic crisis, the “License Raj” ended in 1991 and India tried to liberalize its economy. With the change, Adani quickly launched an export business. The burgeoning empire saw enough success that Adani was kidnapped in 1995 and only freed after his family paid a ransom of $1.5m (Adani also survived another scare in 2008, when he was trapped in the Taj Hotel during the Mumbai terror attack that killed 175 people).

Not long after the kidnapping incident, Adani moved onto a bigger project.

Crabtree writes that Adani had wanted to own a port from a young age after seeing the scale of a government-run facility. And in 1998, the 36-year old college dropout won a government contract to build such a port at Mundra. The site was mostly a marsh land that Adani used as a launching pad for what is now Adani Group.

At the time, India was very short on infrastructure and the relentless Adani built nearby rail links, airports, roads and warehouses to service the port. Mundra found great success focusing on the “3 Cs” (crude oil, containers, coal) and is now the world’s 26th largest port with plans to become #1 by 2030.

Government-run ports lagged in comparison to the Mundra operation and — in the decades since — Adani has added dozens of other ports in India. Adani Group now operates 1/4 of India’s port capacity and pulls in 1/2 of all port revenue.

Gujurat was the start of Adani’s empire and he is now more synonymous with the state than any other tycoon. Unlike Ambani — who inherited his father’s business — Adani wins extra entrepreneurial points for building his conglomerate from scratch. And while Ambani lives in a $1B mansion in Mumbai (dubbed Antilia), Adani has stayed true to Gujarat by living in Ahmedabad, the state’s largest city.

Connection to Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Before Narendra Modi became India’s Prime Minister in 2014, he was Gujarat’s Chief Minister — AKA the state’s head of government — for 13 years.

Modi’s leadership of Gujarat took place during the true heyday of global trade. Over that span, the GDP for China — which entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) the same year Modi started as Chief Minister (2001) — exploded from $1.3T to $10T (now it is $15T). From 2001-2014, India saw slower but still impressive GDP growth: going from $500B to $2T (now it is $2.6T).

As a trade hub, Gujarat was crucial for India’s growth. Modi’s stewardship of the state’s economy — which prioritized infrastructure, foreign capital and export industries — was hailed as the “Gujarat Model”. The region drew comparisons to the Chinese manufacturing powerhouse in the Pearl River Delta (Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shenzhen).

“[Modi and Adani] enjoyed symbiotic careers,” writes Crabtree. “Modi’s pro-business policies helped Adani expand. Adani’s own companies, meanwhile, built many of the grand infrastructure projects that symbolized Modi’s ‘Gujarat Model’”.

Adani was also a vocal Modi defender during one of the Chief Minister’s most controversial periods: a three-day riot in 2002 between Hindus and Muslims which left ~2000 people dead (Modi, a Hindu, was accused of allowing the riots and destruction of Muslim property).

For any ambitious Indian tycoon, a close relationship with the government was a no-brainer in the 2000s. While the License Raj was over, entrepreneurs that wanted to cash in on booming global trade had to play nice with the state if they wanted to profit in rent-heavy industries like real estate, mining, energy, infrastructure etc.

Critics charge that Adani received a lot of preferential treatment during Modi’s Gujarat years: 1) tax benefits; 2) cheap gas for factories; 3) less red tape (eg. waiving environmental reviews); 4) land at a cut-rate prices (especially for Adani’s special economic zone, SEZ); and 5) generous loans and debt relief from state banks.

In return, Adani ably delivered growth, jobs and working infrastructure. Ambani — who split the Reliance empire with his brother in 2002 when his father died — also saw a string of successes in Gujarat.

The Economist notes that the business performance for the “AA” tycoons suggest they have not been out there just extracting rents. Most of the “AA” business lines show returns on capital of less than 10%, which resulted in huge infrastructure builds — “with little regard for profit” — that have benefitted the country (a salient example: in the mid-2010s, Reliance spent >$20B to build Jio, a mobile and data network from scratch which now provides affordable telecom services to 400m+ Indians).

However, close ties between business and government has lead to widespread corruption in India. Politicians often granted land or operating licenses in expectation of kickbacks or money funnelled to shell companies.

For their parts, Modi and the tycoons deny any quid pro quo. It’s naive to think there’s no back-scratching at all, though. Especially when you consider how expensive elections in India cost: Modi spent more than $100m to win the India election in 2014.

The symbiotic relationship is hardly a secret: as the new incoming Prime Minister, Modi flew to India’s capital of New Delhi on an Adani private jet. As we’ll see, Adani’s rise in recent years has dovetailed with Modi’s “Made In India” policy preference for national self-reliance.

Creating an energy empire

In 2002, Adani’s business concerns were worth $70m.

Two decades later, the Adani Group is worth $259B (a ~3700x increase).

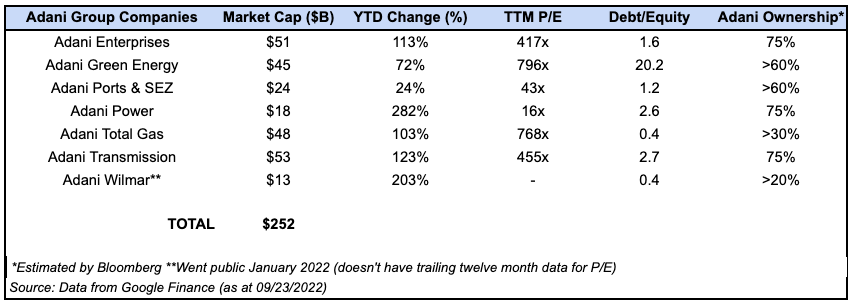

While Adani began his empire with ports, energy is now the main driver. Below is a list of 7 publicly-listed Adani companies. Five of them — Adani Enterprises (which includes coal mining), Adani Green Energy, Adani Power, Adani Total Gas, Adani Transmission — are primarily involved in energy and account for >80% of the group’s $252B total market cap (Adani Ports does, um, ports while Adani Wilmar is in the consumer foods business).

For the average Indian, Adani has built a fully vertically-integrated energy solution: he imports the coal, generates electricity and powers the homes. As coal and energy prices have soared this year, so have Adani’s energy stocks which are all up +72% to +282% (Critics of the stock performance note there are opaquely-structured funds in Mauritius which hold significant stakes in many of Adani’s companies that may be acting to boost prices).

Incredibly, it took Adani only 5 years — 2009 to 2014 — to go from a new energy player to India’s largest private power producer (the process to spin off Adani’s divisions into separate publicly-traded stocks began in 2015).

Adani’s reliance on coal is a huge lightning rod for criticism. Per Bloomberg’s Chris Kay and P R Sanjai, the dirty rock — including a very controversial $15B+ mining project in Carmichael, Australia — accounts for 62% of Adani Group’s revenue.

As someone that lived in Vietnam during a similar stage of country development (2008 to 2013), I don’t think it’s fair for developing nations to be held singularly responsible for coal use when we compare it to Western usage of the energy source in previous centuries. It’s still a problem, though.

Adani — who’s been dubbed India’s King Coal — is aware of the challenge and has committed $70B towards a green energy transition by 2030 (Ambani made a similar commitment). Skeptics are not sold on Adani’s green bonafides but Adani is balancing two competing Modi interests:

Stable energy: India has huge issues with its energy grid and Adani’s operation — even if it’s powered by coal — provides predictable and stable electricity.

Green future: Modi has aggressive climate goals and believes India can be a leader in clean energy (hydrogen, wind, solar). This has the double benefit of reducing reliance for oil imports from Russia and the Middle East.

Take a look again at the table above. Four of the energy-related stocks — Adani Enterprises (trailing twelve months P/E of 417x), Adani Green Energy (796x), Adani Total Gas (768x), Adani Transmission (455x) — are trading at astronomical valuations.

The market is clearly betting that Adani is the man to usher in India’s energy future. Even though the valuations are insane, I kind of get the thesis: if you’re an investor with a bag of cash and your mandate is “I need fat exposure to India’s energy market”, who else are you really going to?

Lots of debt

Ok, so now we have established Adani’s port and energy businesses.

What else? Well, over the past few years, Adani has entered different industries — or expanded into new countries — at a startling pace:

$7B+ for iron ore and aluminum projects

$1.2B for port expansion into Israel (and also a port project in Sri Lanka)

A 30% stake in New Delhi TV (NDTV), a leading Indian media company

Billions to operate 7 airports that carry 1/4 of India’s passenger traffic (this deal raised eyebrows as the Modi government changed the bidding process to allow bids from companies with no airport operating experience…like Adani)

A $10B+ deal for the Indian assets of Swiss cement maker Holcim making Adani the country’s 2nd biggest cement operation (it’s Adani’s largest M&A deal ever; in a recent speech, Adani says the deal is crucial in helping to power India’s growth, which he projects to reach $30T GDP by 2050 with a population of 1.6B).

Adani also has interests in data centres, e-commerce, 5G telecom, agriculture and super-apps (why not?).

How has Adani funded these acquisitions? Primarily through debt.

Since the 1990s, Adani has deployed the following debt playbook per Crabtree:

“Adani credited [his success] to his willingness to take risks as well as a relaxed attitude to debt. He took cash earned from trading, he explained, and funnelled it into infrastructure projects. When those were finished, he used them as collateral to load up more debt to build more projects and so on.”

The current debt pile for Adani Group is $29B+ (vs. group revenue of $30B). In August, a subsidiary of Fitch Ratings said that Adani was “deeply over-leveraged” (a company response showed that its debt servicing ratios have improved in recent years).

But the report also said it “drew comfort” from “policy tailwinds”. This is an absolutely hilarious way to say “ugh, Adani is too big and the Modi government won’t let it fail” without saying “ugh, Adani is too big and the Modi government won’t let it fail”.

The proximity to Modi — and pivot to ESG-friendly green projects — has given foreign lenders confidence to open the check books: huge international investors like Abu Dhabi’s International Holdings, Qatar Investment Authority, Warbus Pincus, and France’s TotalEnergies have given Adani more than $10B.

Lesson: “policy tailwinds” are better than “policy headwinds” (which means the upcoming 2024 Indian election is very very important to Adani Group).

Final thoughts

What can we make of Adani and his fast-growing $142B fortune (combined, me and him have $142,000,000,001)?

The Financial Times brings up an important question: is the concentration of wealth in India a path towards an East Asian model of development (think the Samsung family in South Korea) or the Russian model (oligarchs nabbing state assets on the cheap while creating little value for the country).

Adani clearly has close ties to Modi. Adani Group is over-reliant on coal. The business may be sitting on a systemic debt bomb. AND the value of his stocks are completely removed from business fundamentals.

But, Adani also has a track record of delivering what India needs to develop (ports, rail, infrastructure, electricity). His big bets on export-driven growth and energy also aligns with Modi’s development goals for India.

Whatever you think of him, you have to understand Adani to understand India’s future…and this is my first attempt at doing so.

ADDENDUM: HINDENBURG RESEARCH SHORT-SELL REPORT

UPDATE (02/02/2023): About 4 months after I published this article on Guatam Adani, Hindenburg Research — a short-selling activist firm — released a a report on January 24th, 2023 titled, “Adani Group: How The World’s 3rd Richest Man Is Pulling The Largest Con In Corporate History”.

In my article, I mention the allegations of stock manipulation related to a Mauritius-based fund. That seems to be the tip of the iceberg according to Hindenburg’s 2-year research project, which includes these details:

Today we reveal the findings of our 2-year investigation, presenting evidence that the INR 17.8 trillion (U.S. $218 billion) Indian conglomerate Adani Group has engaged in a brazen stock manipulation and accounting fraud scheme over the course of decades.

Gautam Adani, Founder and Chairman of the Adani Group, has amassed a net worth of roughly $120 billion, adding over $100 billion in the past 3 years largely through stock price appreciation in the group’s 7 key listed companies, which have spiked an average of 819% in that period.

Even if you ignore the findings of our investigation and take the financials of Adani Group at face value, its 7 key listed companies have 85% downside purely on a fundamental basis owing to sky-high valuations.

Key listed Adani companies have also taken on substantial debt, including pledging shares of their inflated stock for loans, putting the entire group on precarious financial footing. 5 of 7 key listed companies have reported ‘current ratios’ below 1, indicating near-term liquidity pressure.

The group’s very top ranks and 8 of 22 key leaders are Adani family members, a dynamic that places control of the group’s financials and key decisions in the hands of a few. A former executive described the Adani Group as “a family business.”

The Adani Group has previously been the focus of 4 major government fraud investigations which have alleged money laundering, theft of taxpayer funds and corruption, totaling an estimated U.S. $17 billion. Adani family members allegedly cooperated to create offshore shell entities in tax-haven jurisdictions like Mauritius, the UAE, and Caribbean Islands, generating forged import/export documentation in an apparent effort to generate fake or illegitimate turnover and to siphon money from the listed companies.

We also identified numerous undisclosed related party transactions by both listed and private companies, seemingly an open and repeated violation of Indian disclosure laws.

The Hindenburg report was released right before Adani was set to issue a $2.4B share sale. Adani ended up pulling the offering after its share price declined below the price of the deal. Combined, Adani businesses have lost $108B since the report (while Adani’s personal wealth has declined to under $70B, half the fortune from when I initially wrote this article).

On February 2nd, Bloomberg said financial institutions are taking a closer look at Adani exposure while the Indian government has yet to sound any alarm bells:

But, in a sign of how risk perceptions are rapidly changing, units of Credit Suisse Group AG and Citigroup Inc. have stopped accepting some securities issued by Adani’s companies as collateral for margin loans to wealthy clients. India’s central bank has asked lenders for details of their exposure to the indebted conglomerate, according to people familiar with the matter.

[…]

The extent of the damage to Adani’s empire may well depend on how Modi’s government responds. The prime minister has so far stayed mum on Hindenburg’s allegations, while the minister for tech and railways told Bloomberg TV that the economy can withstand the rout in Adani shares. Modi and Adani are widely thought to be close, though the tycoon has in the past said he hasn’t sought any political favors.

Adani himself released a video on the same day saying that the conglomerate’s balance sheet is “healthy”:

The Adani wipeout is happening despite a 413-page response from the Indian conglomerate. Hindenburg replied to Adani’s reply with the charge that Adani failed to answer 66 of 82 key questions (further, it says Adani is resorting to the defence that Hindenburg is an “attack against India”).

This entire saga still has many chapters to play out. And Adani’s relationship to the Modi government may certainly influence the outcome. Hindenburg — which sold short various Adani bonds and stocks via derivatives — may make serious gains from their 2-year effort, particularly if all the allegations prove out.

If you’re not a subscriber, toss your email here for more glorious business and tech takes every Saturday:

Links and Memes

Can TikTok replace Google search? The Verge’s David Pierce spent a few days using TikTok as his primary search engine. His conclusion: TikTok is really good with food searches (recipes, places to eat), finding streaming shows to watch and content that benefits from quick and scrollable videos (eg. back stretches). However, TikTok is terrible with general information searches (eg. “USPS tracking”, “weather tomorrow”, “how many ounces in a cup”, “what time does the Super Bowl start?”).

All in all: TikTok isn’t a threat to Google yet but definitely shows instances where “10 blue links — with a bunch of barely labeled ads at the top, a big shopping widget, and a lot of links to Google services — isn’t always the right interface for search.”

YouTube non-skippable ads: One of the funniest running jokes on Reddit is people making memes about YouTube “non-skippable ads” (and how they’ll never pay for the ad-free YouTube premium).

I used to be one of those people but cracked and got YouTube Premium last year. It’s worth it. You obviously pay to get rid of ads but YouTube deviously tucked two must-have features into the paid tier: 1) the ability to download videos in the app; and 2) keep the video playing while the home screen is locked (if you listen to podcasts on YouTube, it’s a no-brainer).

The reason I bring this up is because YouTube has been testing 12 straight non-skippable ads on its connected TV. Thats 3 minutes (12 x 15 seconds). Yes, YouTube has re-created broadcast TV. Eric Seufert writes that YouTube is revving up ad load and he expects 10+ non-skippable ads to successfully nudge quite a few people to YouTube Premium (I’m inclined to agree).

What’s the best team to never win the World Cup? In prep for the upcoming World Cup in Qatar (November), I’ve been watching a lot of YouTube vids. There seems to be consensus that Brazil’s 1982 team is the best team to never win the World Cup. Stocked with talent — including a guy named Socrates who got a PhD in Philosophy — the ‘82 Brazil squad was so dedicated to playing a beautiful game that it ultimately costed them the tournament. Check out this 8-minute highlight package.

And here some gold tweets:

Speaking of the Billy List, Mark Zuckerberg is down over $70B this year…

Speaking of listening to your parents…

In my household growing up, we used to pickle everything Vietnamese-style (carrots, daikon, garlic, lettuce). Happy to announce that I’ve never died of botulism.

Based on the email replies I get, I know some of you are here for the Twitter “Main Character”. We got one a good one this week: Maroon 5’s lead singer Adam Levine.

TLDR: an Instagram Model posted a video saying that she had a year-long affair with Levine, who is married to a Victoria’s Secret model Behati Prinsloo (they have two kids with a third on the way). The IG model posted steamy DMs to prove allegation. Levine put out a statement admitting he sent regretful DMs but says there was no physical contact…but then other woman came forward with screenshots of flirtatious DMs from Levine.

There are ALOT of memes referencing the DMs but — for any fans of Maroon 5 — this next tweet should bring a chuckle: