H-Mart Stays Winning

How the cult grocer went from a single Korean corner store in Queens, NY to America's largest Asian supermarket with $1B+ in sales.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we talk about the Asian supermarket chain H-Mart.

Google acquires Wiz for $32B

Wild story of Netflix defrauded for $11m

…and them fire posts (including B2B SAAS)

PS. SatPost will be off next weekend (no e-mail newsletter on March 29th).

I remember the first time I rolled up to an H-Mart.

The speciality Korean grocer turned America’s largest Asian supermarket — which recently crossed $1B in annual sales — had opened a new store in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I was pumped because the Asian offerings in major grocery chains were pretty flaccid. It’s always a sad aisle or two with some bottles of soy sauce, fish sauce (maybe), Sriracha and a few bags of Thai basmati rice.

Someone had told me H-Mart was an “Asian Whole Foods”. I was expecting a bounty of goods. But it was during a period of peak ZIRP Whole Foods, so I was also prepared to get clubbed over the head with the equivalent of a $6 bottle of asparagus water (literally, a bottle of water with a few spears of raw asparagus)…probably with an Asian twist, so maybe lemongrass water.

Thankfully, H-Mart was infinitely better than that description.

I was at the grocer to prep for hot pot and H-Mart’s hot pot game is very proper.

Hand-pulled noodles? Check.

Dozens of hot pot soup bases including Tomato, Sheep, Hot & Spicy, Beef Tallow and Sichuan? Yes.

Frozen sliced wagyu beef and intestines? Yup.

Fresh oysters, mushrooms, taro root and bok choy? 100%.

Comically-large tubs of kimchi? Is the Pope Catholic?

That was just the hot pot section.

I’m a big sauce guy and H-Mart was rocking every Asian condiment I could ever want. All types of crunchy chili pastes that will put you on the dumper for an hour the next morning but totally worth it the night before. Ramen? Entire walls of incredibly unhealthy sodium-heavy (but absolutely delicious) flavours from Korea, China, Japan and Southeast Asia. The pre-made packaged meals (sushi, pork belly, unagi and bulgogi bowls) go so so so hard. A bounty of prawn crackers, salmon skin chips and random Asian jelly snacks with next-level engineering on the plastic caps and tubes.

When you’re done shopping, you roll out to a top-tier food court. H-Mart handpicks the vendors across its 100+ stores in North America (89 in the US and 13 in Canada) and they all seem to slap. I crush on Costco hot dogs and pizza but it’s mostly just a joke at this point. The real food court action is at H-Mart, with bowls of udon noodles and massive pork tonkatsu curry plates (here’s a trick for first-timers: just point to the top left of the menu, that’s usually the go-to item).

The entire shop is very affordable, too. Definitely not Whole Foods prices.

Anyway, I tell you all this because Bloomberg Businessweek recently published a long profile on the privately-owned chain and it had some great tidbits (“How America Got Hooked On H-Mart” by Adam Chandler).

H-Mart was founded in 1982 by South Korean immigrant Il Yeon Kwon. The first store was opened in Queens, New York and called “Han Ah Reum” (which is Korean for “an armful of groceries”).

Kwon’s go-to market strategy was straightforward: sell Asian goods (rice cookers, aluminum-lined ramen pots, meats, seafood, vegetables) in neighbourhoods that didn’t sell them.

In the first 15 years, H-Mart followed that formula to open five stores across New York and New Jersey.

H-Mart’s 6th location was when the real expansion began. In 1997, H-Mart opened in Falls Church, Virginia. Why? The larger Fairfax, Virginia region was home to the 3rd largest Korean population in America after New York and Los Angeles. The momentum picked up from there and H-Mart added over 30 stores — including in the Midwest and California — over the next 15 years.

By the late-2000s, the brand officially changed its name to “H-Mart”, which was already a popular nickname because “Han Ah Reum” doesn’t exactly roll off the Western tongue (and there were increasingly a lot of non-Korean shoppers).

Admittedly, I can’t even pronounce the OG name. Although that’s probably not a surprise since my Vietnamese language skills are meh (to wit: I was once told by a cab driver in Saigon that “you speak Vietnamese like a white guy”…and I still have psychological scars from that conversation).

H-Mart’s recent growth plan has capitalized on America’s changing demographic and the retail real estate apocalypse, per Bloomberg:

In the years since H-Mart first opened, Americans of Asian descent have surged from 1.5% to 7% of the population, and the retailer has sought out the communities that best reflect that growth. From 2004 to 2009, for example, four H-Marts opened in cities outside Atlanta—Doraville, Duluth, Johns Creek and Suwanee—two of them in Gwinnett County, which now promotes itself as “Seoul of the South” because of its booming Korean population. […]

As the company’s footprint in the US has grown, so has the size of its stores. By 2021 it had more than 50 stores across a dozen states, mostly in the Northeast and on the West Coast. That year it opened its first San Francisco location, a 47,000-square-foot behemoth that soon took over the space once used by a 24 Hour Fitness next door, adding an additional 27,000 square feet. Then, last year, the company went from anchor tenant to owner, buying the entire strip mall for $37 million. […]

Increasingly, H Mart is also succeeding quite literally where other grocery stores have failed. Many of its new stores have been built out of enormous husks once occupied by other supermarkets: a 69,000-square-foot former Vons in Orange County, California; a 64,000-square-foot former Stop & Shop in Long Island City, New York. During the pandemic, two faltering Albertsons in Irvine, California, became 50,000-square-footers. And earlier this year, out of a dead Kmart in Utah, rose a 100,000-square-foot store, H-Mart’s biggest yet.

While reading the H-Mart story, I kept thinking about parallels with two cult-y brands that I covered on my Caffeinated Deep Dives podcast series: Trader Joe’s and Sriracha.

All three brands started slow and built a devoted customer base through word-of-mouth. Instead of spending money on advertising, they all poured resources back into the business. The promise of decent quality and affordable prices created a white-hot core of supporters who did all the evangelizing. With a guaranteed base of support, the brands could think long-term. They steadily compounded sales and reputation over decades instead of eyeing quick (but ephemeral) wins.

The Sriracha story is particularly relevant. As with H-Mart, Vietnamese-American refugee David Tran started his business in the 1980s. Sriracha became a staple in Vietnamese and Chinese restaurants that otherwise had few Asian hot sauce options. Now, Sriracha is a staple in basically every household.

Both businesses were self-funded from savings as the VC industry wasn’t keen on the Asian pantry game and banks were (understandably) not great at underwriting jalapeño-based sauces (Tran may have the best start-up capital story ever: he started Huy Fong and its Sriracha sauces with $20k of gold bars that he had smuggled out of Vietnam in condensed milk cans).

Sriracha has remained a private business with Tran’s children all in leadership positions. According to Bloomberg, H-Mart is also a family affair:

The H-Mart story might have ended with that first shop had Kwon not met Elizabeth, who’d become his wife, shortly after opening. Elizabeth, who grew up two blocks away, would join him in plotting H-Mart’s expansion, designing its locations and leading its marketing operations. Eventually their daughter, Stacey, who grew up bagging groceries in the Queens store, would take charge of creating H-Mart’s new food halls, which evolved from a few simple stalls in the chain’s older stores into the buzzy entities they’ve become. And though the Kwons’ son, Brian, initially resisted the pull of the family business, moving to Seoul at one point, he eventually came home to select and import the retailer’s cornucopian inventory.

Despite its success, H-Mart remains a tiny fry in the grand scheme of things. Annual sales for the entire grocery industry in America is approaching ~$900B.

Meanwhile, the top four players — Walmart (Sam’s Club), Costco, Kroger (Ralphs, Dillons, Smith's etc.), Albertsons (Safeway, Randalls, Carrs etc.) — account for roughly half of all sales. That concentration is one reason that US anti-trust regulators blocked a $25B merger between Kroger and Albertsons.

H-Mart has a ton of room to run, though.

The brand is particularly well-placed to keep serving America’s growing Asian population. Particularly because the Asian grocery niche — unlike the broader grocery industry — is extremely fragmented with frequent store openings and closures.

Go to Little Saigon or Chinatown or Little Italy or K-Town or Little India or [insert ethnic community] of any city and you know what I’m talking about. Mom & pop shops everywhere. These exist for the same reason “Han Ah Reum” started all the way back in 1982: for many immigrants, one of the easiest first businesses to start is a restaurant or grocer catering to other immigrants.

Back in 2020, I was reading Matt Stoller’s newsletter (BIG) about corporate monopolies and antitrust. Stoller received a note from a reader who supplied Asian grocers and — if you’re interested in the minutiae of Asian Grocery Economics™ — this will be one of the best things you’ll ever read (note: the numbers are a bit dated):

I run a family grocery import business in [California]. We import mostly from Taiwan, Thailand and China. I know first hand all the issues relating to outsource to China because I saw those manufacturing facilities up close whenever I went to visit China. We distribute to just about all the Asian grocery stores in the country as well as regular supermarket chains and some of the big concentrated buyers that you had described in one of your earlier articles.

The Asian grocery industry is the complete opposite of the monopolies that you have been describing. In Asian grocery stores, you are looking at the best example of an infinite number of competitors in the supply/demand curves. There are about 1,000+ stores (imprecise number) across the country. None of them are publicly traded, they are all privately owned, including the largest chains.

The largest chains are H-Mart (Korean) 79 locations, 99 Ranch (Chinese) 53 locations, Seafood City (Filipino) 27 locations, and Island Pacific (Filipino) 16 locations. Everyone else is under 10. All these grocery stores are serviced by about 100 importer distributors like us. Again, other than JFC which is owned by Kikkoman, all of them are privately owned.

For comparison’s sake, the US has about 25,000 supermarket locations and they are serviced by 4 national and 8 regional distributors. The largest domestic chains are Kroger (2700+ locations), Albertsons (2,400 locations), and Ahold Delhaize (2,200+ locations). Use your math and you can see the domestics chains are much more concentrated versus the Asian chains (top 3 is over 30% vs 10-15%).

There is no entry barrier for Asian grocery stores. Just about anyone can open a small market and just about anyone can buy a container or two from Asia and start distributing locally. It's the industry of choice for 1st generation immigrants who don't necessarily have fluency in English. In this kind of extreme competition, most compete by pricing. Some of the larger ones can get very profitable while it's a struggle for others. The way for most retailers to get profitable is by cutting costs in as many places as you can. Because of the intense competition and the ease that one can open a new market, there is no consolidation like that of domestic chains.

So what do you get in an industry that has an almost infinite number of competitors? You don't get a high degree of professionalism (the margin can't afford to pay top dollars for talents other than the ownership family), very stagnant business model (too expensive to try anything new), lack of reinvestment (Most stores would never remodel, even after 20+ years of operations). New concepts will only come with new stores, none of the existing stores would even think about doing something new or different.

Incredible intel. Anecdotally, the story checks with Asian communities I spent time in through the years. A lot of first-generation immigrants that open these stores are grinding so that they can afford tuition for their children to go to university and hop on the “lawyer, engineer, doctor” ladders. On the other side of the coin, how many 2nd generation immigrants want to run grocery stores? Seems like a small fraction.

The entire set-up helps to explain the look and operation of mom & pop grocers.

But there is definitely a charm to the small-shop look and part of H-Mart’s appeal is that the chain keeps the DNA of its early days.

Let me explain how with a random quote from a 1999 film called The Corruptor. It starred the legendary Hong Kong actor Chow-Yun Fat as an NYPD officer, who teams up with a detective played by Mark Wahlberg. There’s a scene when the two are driving around in a car while Chow-Yun Fat is eating beef intestine noodles and he tells Wahlberg that “you wanna be a Chinese, you gotta eat the nasty stuff” as code for how to fit in while doing cop work in Chinatown.

I’ve been laughing about that line for decades because I use a version of that quote to rate Vietnamese restaurants, which now have large non-Vietnamese customer bases. Specifically, if I order Bún bò Huế, it better come with skin-on pork knuckles and blood clots because that’s the original recipe (“you wanna be a Vietnamese, you gotta eat the tendons”).

The Corruptor kind of flopped, so most people have zero context when I say the quote and probably find it semi-offensive. I don’t feel bad because everyone should be Chow-Yun Fat maxing (Fat and John Woo’s Hard Boiled is one of my three most-rented Blockbuster films ever).

What does this have to do with H-Mart? In an interview with the New York Times in 2021, Kwon’s son Brian told the paper “we don’t want to be the gentrified store.” It’s trying to stay authentic. A much more diplomatic way of saying “we keeping the nasty stuff” if you will. That means giant tanks of live fish, lobster, shelled seafood and abalone. That means intestines, tendons and all cuts of meats prominently displayed. That means sauces of all shapes, sizes and odors.

That’s what I want to see when I roll up to an Asian market — even though I can’t properly pronounce most of item names — and H-Mart delivers the OG mom & pop vibes, even as it has grown to a $1B a year business.

Google acquires Wiz for $32B

Last week, Google agreed to acquire cloud cybersecurity firm Wiz for $32B. It was an all-cash deal and is meant to bolster Google’s cloud business, which has jumped from sales of $26B in 2022 to $43B in 2024…but still trails the two leading cloud players at AWS ($107B in 2024) and Microsoft (~$102B).

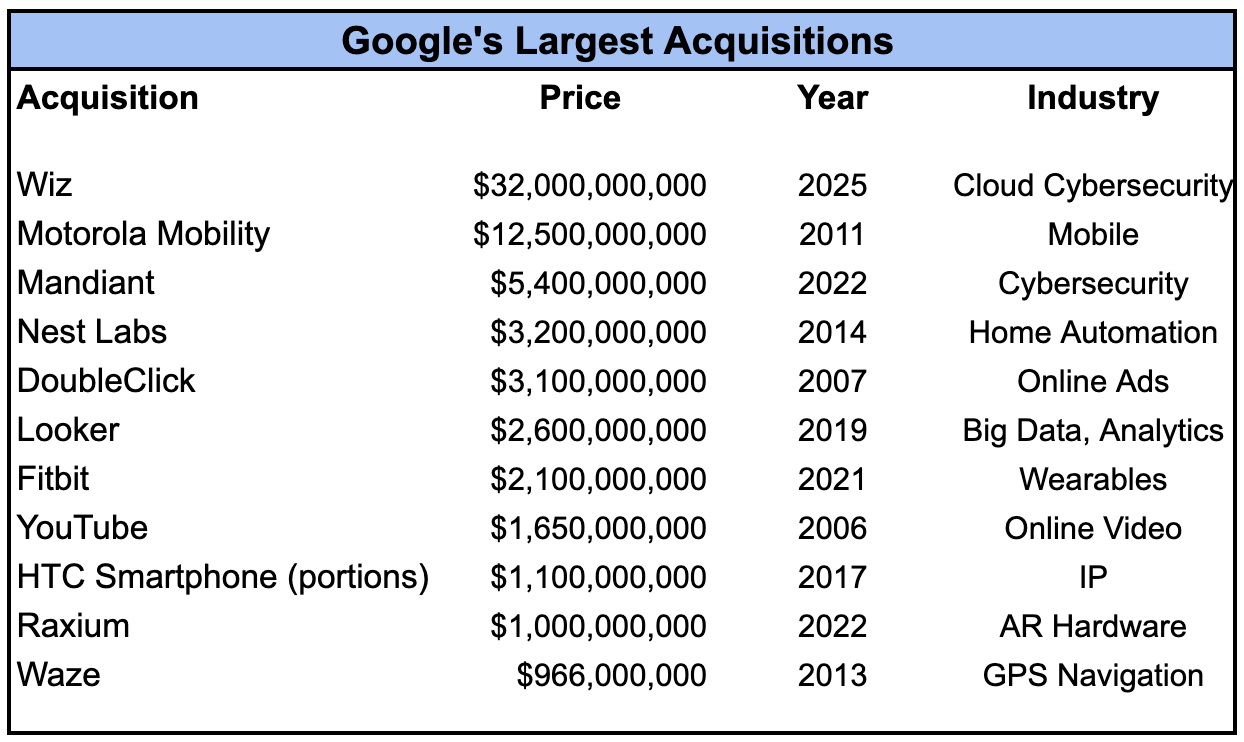

This is Google’s largest M&A deal ever and officially the one I know least about. Everyone is familiar with YouTube and DoubleClick (probably two of the greatest tech acquisitions ever). Most people know the consumer hardware plays such as Nest Labs and Fitbit (the latter is definitely not one of the greatest tech acquisitions ever). Waze for navigation. HTC and Motorola make sense for Google’s mobile business, which itself is built on top of a savvy $50m acquisition of Android in 2005.

I only learned about Wiz in mid-2024 when Google offered to buy the startup for $23B. Wiz turned down the offer and eyed a potential IPO only for Google to turn around and close a deal at $32B. That feels straight out of the Craigslist negotiating playbook. Post some used Air Jordans, get an offer, walk away and then have the buyer up the price. I’m totally imagining Wiz’s CEO Assaf Rappaport telling Sundar Pichai “reverse the numbers on your original offer and we have a deal”.

But a more likely sequence of events is that period from the first offer to the second offer saw a new (and presumably less anti-trust hungry) Presidential administration. If antitrust does block the deal, though, Google agreed to pay Wiz a massive 10% break-up fee ($3.2B) when the going rate for break-up fees is 2-3%. Google will also let Wiz operate as a solo entity during any antitrust review process.

Either way, this wasn’t the Wiz team’s first rodeo: its founding members — former members of Israeli’s intelligence unit 8200 — had previously worked on a cybersecurity startup that sold to Microsoft for ~$300m in 2015. Wiz was founded in 2020 and hit $100m in annual recurring revenue (ARR) only 18 months later, the shortest time it has ever taken a software firm to reach that milestone. The 1,800-person startup is on track for sales of $1B in 2025.

So, what does Wiz actually do? X account Impatient Capital was nice enough to give me a layperson explanation:

Basically...Cloud architectures present unique security challenges, and Wiz is a security software that is specifically designed to search for vulnerabilities and ID risks [or] threats in cloud environments.

[Because] in the cloud you could have a "user" spin up hundreds of "servers" momentarily, move a bunch of data, and then kill those same servers/nodes. How do you know whether that was malicious or OK? Legacy security software relies on assumption of users and assets as relatively static.

Wiz currently works across all the major cloud providers and will keep doing so because its customer base demands it and regulators would probably be displeased if Google pulled the service from competitors. Even if Wiz customers stay on other clouds, Google can upsell cybersecurity consulting from Mandiant, which is the tech giant’s 3rd largest acquisition ever ($5.4B in 2022) and another company that I have no idea how it operates or what it sells but is probably important.

A public comp that is often brought up for Wiz is Palo Alto Networks, which has a market cap of $120B on annual sales of ~$8B.

One industry insider explained that Wiz’s appeal is ease-of-use vs. existing players:

Most of [Wiz’s] competitors, like Palo Alto, have a very convoluted offering from gluing together several acquisitions. Wiz is very cohesive with a much nicer API and great UX, which is very underrated in the security space imo.

I have zero trust in Google’s promise to keep supporting the tool for multiple clouds or maintain the high quality of product design that makes Wiz great. It’s great for my job security, but I’d call it a net loss for the industry.

X account Wasteland Capital has some interesting takes on the deal (yes, I follow a lot of anonymous accounts with the word “Capital” in their handles):

Google needs to differentiate its Cloud offering: “Google is a distant #3 in Cloud with 12% share, so it needs to grow. And it needs to differentiate itself with unique [unique selling proposition] versus Amazon & Microsoft. In that context, this is a strategically very solid move. It gets a new standalone product that it can sell to anyone and can also (probably?) offer faster, cheaper and better plug-and-play integration for its own Cloud customers.” [note: Amazon is known as developer-friendly and Microsoft gets to up-sell Cloud services through all of its existing enterprise contracts]

Did it have to spend $32B to do it? “But the PR on the deal leaves a lot to be desired. It’s not really clear from the deal description on Google’s site how this is going to impact their growth, margin, or revenue profile. They gave us a lot of stupid “platform” buzzwords, nothing tangible. How did they value this at such a multiple? Plus, with $50bn in annual R&D, one wonders why Google is unable to boost Cloud security on its own? Are they not able to release products effectively (no, it doesn’t look like it)? Why can’t they hire good people for all that cash? And was Google Cloud security really bad before this?”

Was there no other better use of the funds? “Also, considering the recent crash in the Google share price… could this cash have been better spent on a buyback? Let’s face it, $32bn is only 1.6% of Google’s market cap, despite sounding like a lot of money and Google’s largest deal ever. For a strategic move (if that’s what it is?), it’s not much, as such. But some buyback support would have been nice! You need it now! Shareholders are bleeding! You have the lowest multiple among the Mag 7 and still choose to spend on M&A instead? And considering the struggles in their Artificial Intelligence (let’s face it: Gemini sucks versus the competition), it feels like many investors would have rather seen capital allocated to a better product in the AI space.”

Alphabet fell 2% on the news, presumably because I still have no idea what this company does.

“The Case Against Streaming TV Shows”

My piece last week on “The Case Against Streaming TV Shows” received a lot of reader feedback. Thank you for the replies! Always appreciated.

One note I wanted to share is from Joseph Mallozzi, a veteran of the TV business, who is best known for his writing and producing work on various Stargate series (Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis, Stargate Universe) and as a show-runner for Dark Matter.

This was a much-needed take because I’m obviously yelling from the bleachers while Joseph provides an actual insider view on how streaming changed TV economics and incentives. Full thing worth a read but here are takes on hanging narrative arcs and the ideal TV show episode length (my excerpts are in bold while his comments are in bullet points):

"I will not watch Severance until the narrative arc is completely done (or if the show gets cancelled before Season 3, then I will have saved 20-30 hours of my time)."

I notice more and more viewers adopting this attitude, and I get it. I've long argued that there is an unwritten agreement between broadcasters/streamers and viewers that goes something like "You tune in and we'll tell you a story". But broadcasters/streamers have historically reneged on this agreement by canceling shows, leaving narratives unresolved and, effectively, denying viewers that complete story.

Granted, it doesn't make financial sense to grant endless seasons to wrap up myriad plot lines, but I would posit that, if you're going to cancel a show, grant it a dedicated movie or miniseries to offer viewers some sense of closure. As you know, I speak from personal experience with Dark Matter (2015, The space-based far future sci-fi series as opposed to the more recent Apple TV show that is also a sci-fi series with the same title. And title font) that I designed as a response to the make-it-up-as-you-go-along school of TV storytelling where you set up a bunch of mysteries that get strung out over the course of several seasons, consistently contradicting its internal logic, ultimately leading the audience to realize the writers/creator have no idea where they're going — at which point the show is either cancelled or wrapped up in unsatisfactory fashion.

And then we got rug-pulled and our request for a wrap-up movie went ignored. Not turned down, mind you. They just never bothered to respond to the request. This, every so often, is one of the many challenges faced by creators, and specifically creators of serialized shows."[The new streaming TV show I will watch is The White Lotus because it’s] only an 8-hour commitment and I know I’ll get a completed narrative arc by the end. That’s a reasonable ask of my time."

Earlier this year, I posted a poll "What is the ideal number of episodes for a season of television?" Perhaps unsurprisingly given many of my followers are Stargate fans, 20+ episodes was the overwhelming favorite. But, for me, the correct response is...

As a viewer: 6-8

As a series creator: 10-13

As a writer landing a gig on someone else's show: 20+

Speaking of The White Lotus, the previous episode had one of the wildest monologues in recent TV memory (between Walton Goggins and Sam Rockwell).

If you’re watching the show, you know what I’m talking about. Even if not, the facial expression acting by Goggins was so good — YouTubers will be studying this scene for decades to see how to change facial ticks to increase click-through rates by 2.8% — that you don’t even need context to understand this meme.

Links and Memes

Speaking of streaming, Netflix was defrauded for $11m by a film director…who took the funds to YOLO in stock and crypto bets. It’s such a wild story that it’s deserving of a Netflix show.

In 2018, Netflix bought a sci-fi series from director Carl Rinsch. By 2020, Netflix spent $44m on the show (“White Horse”). Production was floundering and Rinsch demanded $11m more. He took the funds and quickly lost ~$6m in pharma option YOLOs. A bit later, he took $4m and YOLO’d into Dogecoin, turning that into $27m.

If you’re keeping count, that means Rinsch actually made back all the money he lost. Did he call Netflix and say “yo, crazy story, but I got your money.” Hahahahah, of course not. He went on a spending spree that would have made that Russian kid from Anora pretty jealous:

$5.4m on luxury furniture

$2.4m on two Rolls Royces

$1.8m on credit card bills

$1.1m to sue Netflix (next level LOLOLOLOLOL)

$395k to stay at Four Seasons

$638k for luxury mattresses

$295k for luxury bedding and linen

$180k on kitchen appliances

Well, I guess he didn’t marry a stripper, so maybe not full Anora. Either way, Kind of a hall-of-fame ZIRP tale.

***

Some other links for your weekend consumption:

The Boston Celtics were sold…for $6.1B to Bill Chisholm, managing partner at Symphony Technology Group. It's a record for US pro sports team, topping the sale of NFL's Washington Commanders at $6.05B. Chisholm’s fortune is a reminder about the absolute monstrous size of the software industry.

UPDATE on Bearly AI: The AI-powered research app I’m building will soon launch a spin-off product that a bunch of users with their own AI apps have asked about: an easy-to-use way to manage all the different LLM APIs for usage, billing and security. We’ve been doing it for years and finally productized it. Keep an eye on this space!

WTF happened to Walgreens? The pharmacy chain has been public for over 100 years, hitting a peak of $107B in the mid-2010s before declining to $7B. It’s now being taken private for $10B. Walgreens (infamously) partnered with Theranos but that was the least of its problems. My colleague at Workweek (Blake Madden) has a great breakdown on what happened to the chain: a combo of a bad healthcare strategy, crushing debt, executive turnover and deteriorating in-store experience.

Shoutout to theSkimm…the newsletter for young millennial women that launched in 2012 and raised $29m to build a next-gen media company. theSkimm was a newsletter OG but became a victim of the VC funds. Investors probably didn’t make any money on the deal (one red flag: no acquisition price announced). It just wasn’t a venture- scale business. My other Workweek colleague Adam Ryan breaks down how theSkimm pioneered a new category but fumbled the execution.

A random tree in Toronto…was marked as a tourist destination on Google. People are visiting it and leaving absolutely wild reviews (“we walked 40 minutes to view Rodney the Tree. It was a glorious and life-altering experience. Be careful not to view the wrong tree, as there is a similar (but far inferior) imposter nearby”). Man, I f**king love the internet.

“You should go touch grass”…as the saying goes when you’ve been online for the past 18 hours. Incredibly, someone took that quip and made an app: Touch Grass Now, which locks selected apps on a smartphone until the user goes outside and takes a photo of actual grass. Top-tier use of visual AI.

AI cheating app…man, this is such a grim video and I’m not even sure if it’s a massive troll. But here’s a clip for what looks to be an app that helps students cheat on in-class quizzes…and apparently vaseline is useful for blocking proctor-monitoring technology…in sum: bring back oral exams.

9-5 influencers…Jenny Zhang has a great article about TikTok influencers that build audiences by posting uneventful “day in the life” videos of their 9-5 jobs. One influencer recently quit his job and kept trying to milk the same type of content but the audience got pissed because he was no longer on the 9-5 grind. A salient example of audience capture and why getting “known” for doing one thing can be detrimental…you kind of paint yourself into a corner. To paraphrase Chow-Yun Fat, “You want to be 9-5 influencer, you gotta do the nasty stuff.”

…and here them wild posts (including on the news that Klarna and DoorDash have teamed up to offer customer orders on interest-free instalment plans…which is obviously an absurd example of financial engineering and was easy to turn into a Big Short joke):

Here’s a sentence you won’t see often: HR B2B SAAS firm Rippling is suing its competitor Deel for corporate espionage. Allegedly, one of Rippling’s employees was secretly working for Deel to snipe large contracts. Rippling sniffed out the scheme then created a “honeypot” — which was a secret Slack channel — to catch the employee doing the dirty deed. Hilarious. But not as hilarious as the fact that when investigators came to take the employees mobile phone, he ran off to the bathroom and tried to flush the device down the toilet (straight out of the Goodfellas bust scene).

Anyways, the related posts were gold: