Hayao Miyazaki: 9 Creative Lessons

Notes on the creative process for the legendary Japanese filmmaker and founder of Studio Ghibli.

Everyone has weird triggers in life.

Let me share two of mine.

Whenever I see a 60-second clip of David Goggins, I feel the urge to do a 10km run.

Whenever I see Hayao Miyazaki talk about creative work, I feel the urge to write.

Damn, Miyazaki goes hard.

That screenshot is from the 2019 documentary 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki. Over the course of a decade, Japanese director Kaku Arakawa was given full access to Miyazaki and the legendary film studio he co-founded, Studio Ghibli.

The sole condition was that Arakawa was the only person filming the project and I’m so happy they came to an agreement on the terms…because it’s an incredible 4-hour artifact on Miyazaki’s creative process.

Miyazaki is now 84 years old and one of film’s most towering giants. The driving force behind 20+ animated classics and arguably Japan’s most successful film studio.

He is the Japanese Walt Disney and Steven Spielberg rolled into one (probably Martin Scorsese too based on his glasses and hilariously blunt curmudgeonly takes).

Arakawa’s documentary has been top of mind for me. In March, ChatGPT launched a new image generator and it seemed that half the internet had AI-generated Studio Ghibli-influenced anime images. It also felt that half the internet was up in arms about Ghibli IP being snatched.

Then, in June, it was the 40th anniversary of Studio Ghibli’s founding.

Within this time span, Miyazaki was being remixed for the future (to the chagrin of many) and celebrated for his decades-long body of work.

This backdrop felt like the opportune time to re-watch 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki and read “Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man: 15 Years at Studio Ghibli”, a book by long-time Studio Ghibli executive Steve Alpert.

I did both and took copious notes on Miyazaki’s career and lessons on creativity including:

The Making of Hayao Miyazaki

Deadlines, Deadlines, Deadlines

The Daily

RoutineGrindTuning The Creative Antennae

The Creative Process Has Different Speeds

Finding The Essence Of The Art

The Importance of One Decider (Father vs. Son)

Pros and Cons of a Mimetic Rivalry

Obsession With Detail

The Making of Hayao Miyazaki

Hayao Miyazaki was born on January 5th, 1941 in Hongō, a district of Tokyo.

His father worked for Miyazaki Airplane, a family business that made rudders for military planes during World War II. Miyazaki wasn’t particularly close to his father but that job in the rudder factory helps to explain Miyazaki’s future interest in airplanes (including the 2013 film The Wind Rises, which chronicles the story of the Japanese inventor behind the Zero fighter plane).

Miyazaki’s mother Yoshiko had four sons and proved to be the true influence in his life. In nearly all of Miyazaki’s films, there is a character that is inspired by his mom and she is why so many Studio Ghibli films have a strong female lead.

While his mother was bedridden for most of Miyazaki’s childhood, her determination left a lasting impression because Miyazaki himself was quite sickly growing up in war-torn Japan. Miyazaki’s slight figure made him the target of school bullies (what douchebags) and he had such bad digestive issues that one doctor said he wouldn’t live past 20.

Understandably, this childhood left emotional scars. But it also seeded a lifelong drive to create.

“I want people to have fun [and] that’s my motivation,” Miyazaki explains in 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki. “It is because if I can entertain people, maybe I deserve to exist. I have this repressed need to feel useful. That was probably formed in my childhood [but] I don’t want to dig that up. I just like people to have fun.”

Miyazaki found his outlet to help people “have fun” through animation.

Interestingly, a lot of notable creatives have turned a difficult childhood into fuel for incredible success including two famous American directors born around the same time as Miyazaki:

Francis Ford Coppola (b. 1939): Coppola’s filmmaking journey began in childhood when he was partially paralyzed after contracting polio and spent countless days in bed re-making theatre plays to pass time.

Steve Spielberg (b. 1946): The director struggled with dyslexia as a child. Teachers thought he was lazy and other students bullied him. Film was an outlet: “Movies really helped me, kind of saved me from shame, from guilt, from putting it on myself…I think making movies was my great escape, it was how I could get away from all that.”

Miyazaki’s first taste of animation was a 1958 Japanese film titled Panda and the Magic Serpent, which inspired him to create original stories rather than copy existing work (this is a notable difference with Walt Disney, who really made his hay by adapting older fairy tales).

At University, Miyazaki studied political economy and pursued art on the side by spending time in a children’s literature club. He graduated in 1963 and joined Toei Animation to work on children’s TV shows. Apart from learning the trade, the most important outcome of this role was that Miyazaki met Isao Takahata, a director and future co-founder of Studio Ghibli.

Through the 1970s, Miyazaki and Takahata bounced around different animation studios as a creative Jordan and Pippen duo on film and TV projects. Miyazaki’s reputation grew within the industry but his perfectionist style led to delays and frequent clashes with producers.

To realize his ultimate creative vision, Miyazaki needed full control and one film changed everything: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Released in 1984, the fantasy film was based on a manga series that Miyazaki had illustrated over the prior three years. The manga work was commissioned by Toshio Suzuki, the editor of an anime magazine called Animage.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was set in a post-nuclear world, where surviving humans try to navigate a semi-hospitable environment.

While Miyzaki had grown up watching anime with children-focussed stories, he used the medium to convey more mature themes and would do so for decades.

His first film was a creative and commercial success, thus giving Miyazaki and Takahata the leeway they needed to launch their own studio in 1985. Miyazaki named it Studio Ghibli, which draws on the Italian word “ghibli”, which itself draws on an Arabic term for “hot Sahara desert wind”.

Studio Ghibli’s mission was to blow a new (and presumably hot desert) wind into the animation industry.

By 1989, Suzuki — the anime magazine editor — had joined Ghibli full-time and is considered a co-founder for his early efforts to get Miyazaki to create the Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind manga.

Sadly, Miyazaki’s mother passed away a year prior to the film’s release. She never got to see his magisterial works but her influence inspired him throughout his entire career (and is memorialized in many of the Studio Ghibli films).

Deadlines, Deadlines, Deadlines

Miyazaki was 43 years old when Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind thrust him to the upper-echelon of Japan’s film industry.

That desert wind was blowing hot AF and there was no letting up now.

Regularly working 18-hour days, Miyazaki pushed his team — that would grow to 100s of animators in the 1990s — at an unrelenting pace.

According to former Studio Ghibli exec Steve Alpert, Miyazaki’s “way of making a film was particularly stressful, and that was exactly how he thought it should be…he would often say that a person only does his best work when faced with the real possibility of failure and its real consequences.”

As someone that was once told he’d have to wait a year to do a driving test if he failed a 3rd straight driving test, I can attest that “the real possibility of failure” is one hell of a motivator (I did finally get my driver’s license but will never forgive the tester for making me parallel park at three different spots just to make sure I wasn’t an idiot).

At Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki created the same pressures and “real possibility of failure” by instituting tight deadlines, per Alpert’s book “Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man”:

Hayao Miyazaki’s reputation in Japan was such that once the film was announced, every theater in Japan already wanted to play the film. The film was almost always announced in December. Year-end was always a good time in Japan to get people’s attention. The film would be released to theaters in mid-July two years later, the best time to play a film in Japan because schools would be on vacation.

Miyazaki’s skill at delivering his films on schedule was what made this kind of scheduling possible. But his process was never easy, or even certain. Miyazaki simply believed that animated filmmakers should always work under the gun. The studio only missed the July deadline once, and this was due to extenuating circumstances beyond the director’s control.

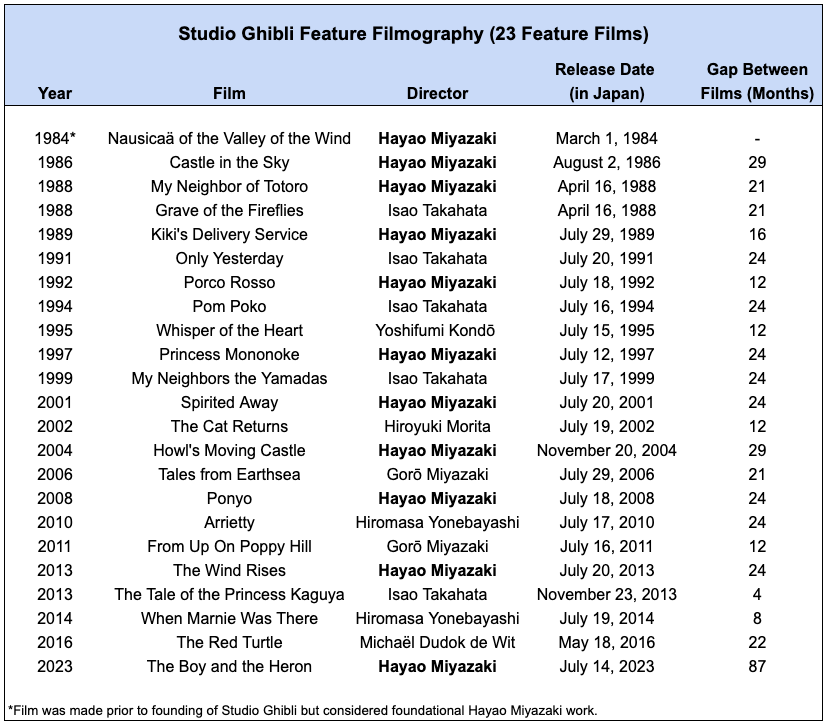

Studio Ghibli films were released on a punishing cadence, as shown by this table:

Tight deadlines are obviously not a one-size-fits-all solution. But reading through Studio Ghibli’s process reminded me of another animation shop that consistently cranks out unbelievably creative content on tight schedules: South Park.

Trey Parker and Matt Stone produce their legendary cartoon on a weekly cadence.

That pace is wild compared to a more typical once-per-month episode pace for other popular animated series. In the documentary South Park: 6 Days to Air, Parker explains why the time crunch works for them:

I always feel like, “Wow I wish I had another day with this show.”

That’s the reason that there’s so many episodes of South Park. We’re able to get it done because there is just a deadline and you can’t keep going. Because there’d be so many shows that I’m like, “No no it’s not ready yet, not ready” and I would have spent four weeks on one show.

All you do is start second guessing yourself and rewriting stuff and it gets overthought and it would have been 5% better.

I think it is important to note the difference between a deadline and “rushing”. As Parker says, more time doesn’t necessarily equate to better work. Sometimes it is best to not have “overthought” and to just ship the product.

In Miyazaki’s case, a deadline does not equate to shortcutting of the creative process as we will discuss in the next section.

The Daily Routine Grind

In 2021, Peter Jackson released an 8-hour documentary on The Beatles. The project follows the British super-band in 1969 as they write and rehearse songs for their second-last album “Let It Be”.

The documentary is unreal and the best review I read was from British writer Ian Leslie, who characterized the band’s process as “the banality of genius”:

Watching extraordinary people do ordinary things is also just oddly gripping. I loved witnessing the workaday mundanity of The Beatles’ creative life.

Turning up for work — for the most part — every day, at an agreed time: Morning Paul. Morning George. Taking an hour for lunch, popping out for meetings. Sticking up your kid’s drawing by your workstation. Confessing to hangovers. Discussing TV from the night before. Fart jokes. Happy hour at the end of an afternoon. Coats on: Bye then. See you tomorrow. See you tomorrow.

This is exactly how I felt watching the first episode of 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki, when Miyazaki is working on his new film Ponyo (about a fish princess with a human face).

Miyazaki’s daily routine is “predictable” and as ordinary as it comes:

He pulls up to his personal office in a Citroen 2CV.

The office is a 3-minute walk from the Studio Ghibli office (but Miyazaki likes to work solo during the ideation phase).

He opens the door to his two-floor office and says “hello” to no one.

Then, he opens all the windows in the office and makes a fresh-looking drip coffee.

He and an assistant cart a wooden bench in front of the office. They hang a “have a seat” sign on the bench so that anyone can sit down (Miyazaki likes to observe people).

“The trap is set,” he says of the bench. “It’s in the everyday, ordinary scenery, where I discover the extraordinary. Ideas come from the unexpected.”

He starts drawing manga strips to get the ideas going…but it’s a slog.

He tells the documentary director that, “Nothing’s working today. Don’t waste time [recording] this. Don’t think you can always capture what you want.”

Then Miyazaki drops the most relatable mid-afternoon quote I’ve ever heard: “I’m sleepy. Time for a nap.”

He comes back the next day and the slog continues: “I don’t know. I’m in a rut.”

He draws something and thinks that there is a breakthrough. False alarm: “No, this is not right. I just can’t pin it down. I feel like I’m drifting.”

The documentary captures Miyazaki doing this routine for two straight weeks with nothing tangible to show for the effort (Mason Currey has a fantastic 43-screenshot thread if you’re looking for the process in Twitter format).

Look, I know this sounds petty but you have no idea how good it felt to see one of the greatest animators ever just fumbling around.

I screamed, “He’s Mortal!” right before clicking play on a 26-minute highlight package for Lionel Messi’s 2022 World Cup run.

Well, Miyazaki is indeed “mortal”…for a little while anyways…because he just keeps on grinding. He wakes up and repeats the same rituals over and over again. That’s the fucking magic. There is no secret sauce. Miyazaki comes back every day, does his routine and sits at his work desk.

A few years ago, legendary sci-fi writer Neal Stephenson did a Reddit AMA and someone asked, “I feel like there’s a lot of good resources for improving one’s storytelling ability, how does an [aspiring] author improve their prose?”

Stephenson’s answer cut straight to the point: “Stop thinking of it as art or something you are born with. Start thinking of it as an acquired skill like cabinet making.”

Watch the documentary of The Beatles or Miyazaki or South Park and it’s all the same. They are making cabinets.

Of course, these are all insanely-talented individuals. But their timeless outputs are the result of putting in tens of thousands of hours and reps.

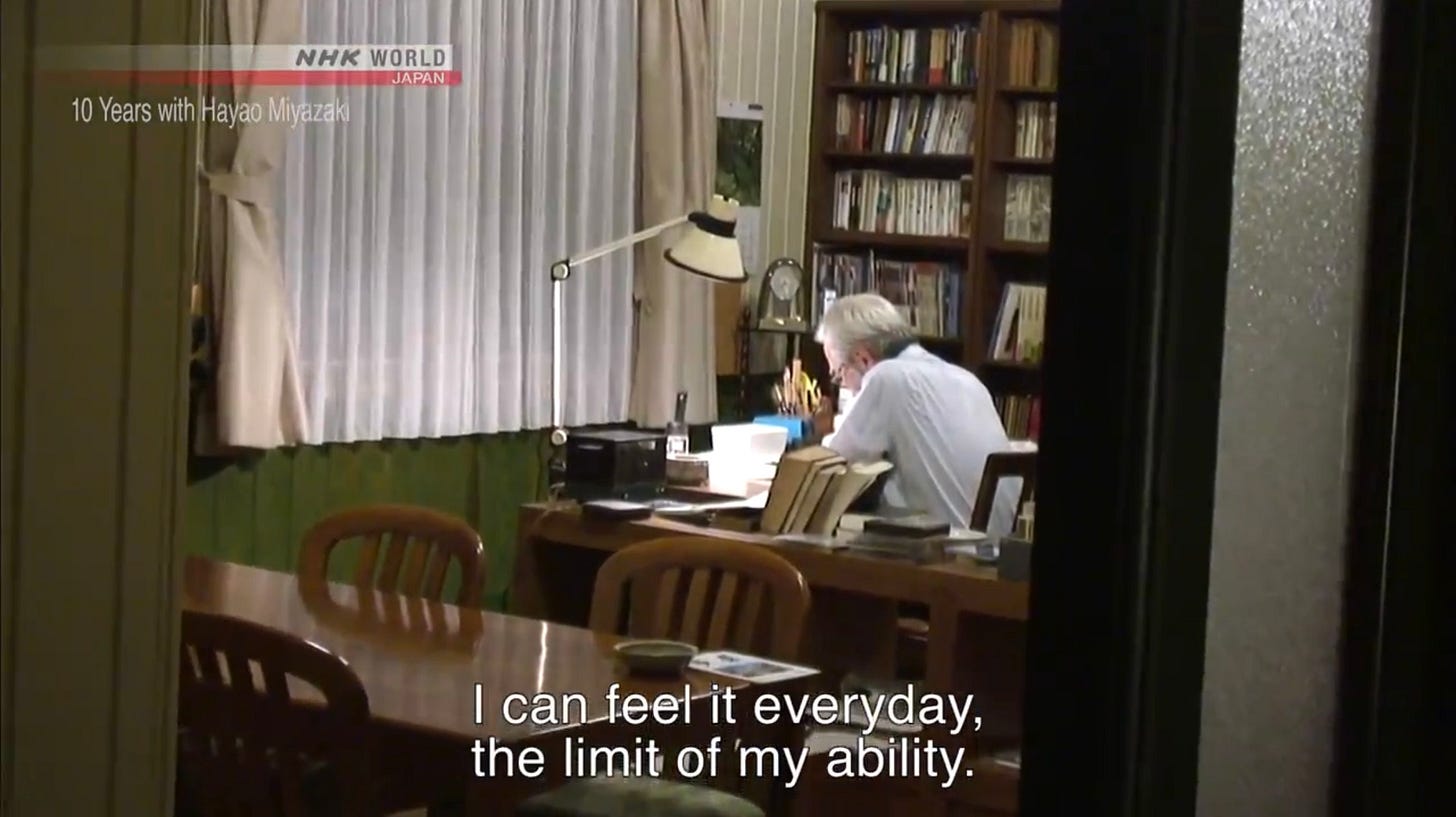

Miyazaki was in his late-60s during the course of the 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki documentary. After more than 40 years of drawing, his grip isn’t as strong and he has to use softer pencils.

“I can feel it everyday, the limits of my ability,” he tells the director, Arakawa. “It takes so long to get things done nowadays. I can’t help it, no point on dwelling on it.”

He doesn’t dwell on it and keeps grinding.

That’s how his last film — The Boy and the Heron (2023) — was released when Miyazaki was 82 years old. Incredible.

Tuning The Creative Antennae

Here’s a solid paragraph from Rick Rubin’s book “The Creative Act”:

We are all antennae for creative thought. Some transmissions come on strong, others are more faint. If your antenna isn’t sensitively tuned, you’re likely to lose the data in the noise. Particularly since the signals coming through are often more subtle than the content we collect through sensory awareness. They are energetic more than tactile, intuitively perceived more than consciously recorded.

I’ve heard Rubin talk about how he likes to leave the radio playing on background while he’s doing other stuff. Sometimes there is a new song he’s never heard and he’ll have his assistant call the radio station and ask for the name of a song played at a specific time.

That’s quite a literal interpretation of someone using their antennas to seek out creative transmissions.

Miyazaki tunes his antennae in a few different ways. As shown at the start of his daily routine, he pulls out that bench in front of his office with the “have a seat” sign. This allows him to observe strangers looking for a quick rest.

Later, Miyazaki installs a camera in his car and drives around the neighbourhood recording stuff.

“I just want to find out what I’m seeing everyday,” he explains to a colleague. “It’s in the everyday, ordinary scenery where I discover the extraordinary.”

An apt example of Miyazaki “discovering the extraordinary with the ordinary” is one of his most beloved characters: the Catbus in My Neighbor Totoro.

That feline-shaped vehicle made contact with Miyazaki’s creative antennae while he was observing a bus stop near his office.

In the documentary, Miyazaki’s car camera doesn’t yield any fruit. He thinks the camera was too high and only captured the sky.

Still, Miyazaki’s point has been made.

Unsurprisingly, he has a whole notebook of unfinished ideas and flips through it looking for inspiration.

Leaving the office is a crucial source of inspiration: “I can’t just sit at my desk, ideas come from the unexpected.”

There’s a whole town in France that inspired his 2004 film Howl's Moving Castle.

Meanwhile, during his ideation phase in the documentary, Miyazaki visits the Tate Museum in London and his antenna is piqued by a painting by Sir John Everett Millais (“Ophelia”).

The art piece deeply inspires him.

“I thought, my work is shoddy compared to those artists,” Miyazaki laments. “I was just astonished [by “Ophelia”]. At that point it became clear to me. Our animation style could not go on as before. I mean, I’m at a dead end.”

As shown below, the Millais painting (top) finds its way into the Ponyo film (bottom):

Perhaps my favourite sequence of Miyazaki re-tuning his antennae is when he goes to a seaside town outside of Tokyo so he can really stew on Ponyo.

“If you don’t change up your surroundings, it’s hard to break out of a creative rut,” Miyazaki tells Arakawa. “That’s why travel can be so stimulating”

He stares out at the water. Walks around. Says “hi” to some locals, many of which know him well from his creative getaways. He grabs some groceries. Then, Miyazaki goes to his accommodation to cook sliced beef and onion (god damn, it looks tasty).

The creative breakthrough doesn’t come right away, though.

Arakawa asks him: “To make a film, do you need periods of solitude?”

Miyazaki isn’t really in the mood for any company:

How would I know? Everybody’s different. I want to stay grumpy. That’s who I am. I want to get lost in my own thoughts. That’s not socially acceptable, so I plaster a smile on my face. Everyone feels like that sometimes. Why would I smile when I’m like that? Films are made at moments like these. The more we get into the film, the more irritable I get.

Alrighty then, on to the next.

The Creative Process Has Different Speeds

At this point, you can probably tell that Miyazaki is prepared to wrestle with an idea for a very very long time before he feels like it is ready.

There’s an instructive sequence from the first episode of the documentary when Miyazaki is trying to nail down the essence of the Ponyo's story.

He sits at his desk and sighs, “I don’t know. I’m in a rut. This morning I thought we had a starting point. But now I have doubts.”

He creates a story board he likes and is pumped. But it is a false start. He tosses the work in the garbage — I felt this pain so viscerally — and slumps, “I know it’s not right.”

Miyazaki isn’t discouraged, though. He’s been through this creative nadir many times before and knows that it is part of the process: “I’m back in this again. The film making has begun.”

There’s a solid three weeks of progress and Miyazaki starts showing his producer Suzuki some of the work. It’s moving along but still incomplete, “I just can’t pin it down. I feel like I’m drifting.”

Eventually, Miyazaki says the problem is that he doesn’t want to repeat himself: “I’m just not interested in conventional story openings anymore. Easy-to-understand movies are boring. Logical storylines sacrifice creativity. I’m all about breaking convention. Kids get it. They don’t operate on logic.”

One evening, he sits at his desk and puts a CD for Wagner’s “The Ride of the Valkyries” and writes a note to his team, “We must be idealist realists. Pure realists without dreams are a dime a dozen. Pure realists are the worst. I don’t want our team to be like that.”

Another night, he pulls out an old box of pastels from his desk drawer. He’s never actually drawn with them but wants to see if a new grip and feel can trigger new ideas. It helps.

As Miyazaki works through creative hell, there are hundreds of Studio Ghibli animators waiting for his vision to come to life.

Everything at the studio hinges on him. Typically, Miyazaki provides a storyboard and his team animates the scenes. But since the animation process is so time-intensive, Miyazaki has to start handing over materials even before the story is done.

Steve Alpert explains Studio Ghibli’s 5-part development process:

Early on in the production process, things would proceed at a fairly leisurely pace. Miyazaki drew the storyboards, which Ghibli called the econte. The econte was a combination storyboard and screenplay, a complete menu for a film that served as a blueprint from which the film could be made.

Miyazaki usually divided the econte into five parts: A, B, C, D, and E. These were not acts like in a play. Each was just approximately 20% of the expected length of the film. Miyazaki usually had all of Part A and most of Part B in his head when the film was first announced. The images in Part A would be lovingly and carefully drawn in some detail. For his later films, when he knew the econte for all of his films were being displayed in the Ghibli Museum, Part A was executed in delicate watercolor. The drawing in Part B was also done at a more deliberate pace. Once Miyazaki began drawing Part C, the film would go into full production.

The background artists and the composition artists would have already begun, but now the animators were beginning to draw. Miyazaki was both finishing writing the film and beginning to meet with animators to review animation drawings. By the time Miyazaki started Part D, he would begin having doubts about whether the five parts and the length assigned to the film would be enough to contain the story. He usually had no idea how the film would end. He might have competing ideas about how it should end that he couldn’t resolve.

Or he might have no idea at all. The animators would be catching up to Part D and the writing process would slow to a crawl. A sense of impending crisis would seep into the studio. Miyazaki would stop writing and spend his time doing things unrelated to the film. He’d chop wood for his studio’s Vermont cast-iron stove. Someone would report this to Suzuki, who would go over and try to get him to stop chopping wood and get back to work. Part E had not yet appeared, and the entire studio would exude an atmosphere of high stress.

Here’s a visual of the econte for Ponyo.

In episode 4 of the documentary, Miyazaki struggles to finish the final few econtes for The Wind Rises and the entire production has to wait on him.

Miyazaki eventually cranks out the scenes and is almost in disbelief when it’s done.

No matter how many times he’s been through the creative process, it’s still a minor miracle when completed.

Watching Miyazaki go between two creative speeds — ideating (“chopping wood for a Vermont cast-iron stove”) and grinding hard AF (“finishing writing the film and beginning to meet with animators to review animation drawings”) — reminds me of something John Mayer once said about his song-making process.

Speaking on Rick Rubin’s podcast, the musician talks about letting the creative search process happen organically. But when the vision is clear and he cracks the code, it is time to lock down and go HAM:

[Cracking the code is the] best feeling…I see young artists sometimes with a hard drive full of minute and a half-baked ideas that were just the spark and they move on to another spark and they move on to another spark and they move on another spark.

And I'm like “[if you crack the code]…you don't leave the room. You put sweatpants on, you're in a hoodie, you're not going out tonight [and you work for the next few days until you’re done].

Why? Because the greatest thing is about to happen to you. And all these songs that I play on stage now represent a night I said ‘Shut it down, we got work to do.’

Maybe the secret is to chop wood while wearing sweatpants? I’m not sure but will absolutely have to look into it.

Finding The Essence Of The Art

Steve Jobs famously said innovation is "saying ‘no’ to 1,000 things before you say yes.”

To instill this idea and other lessons for new Apple hires, Jobs launched the Apple University in 2008 with the help of the dean of the Yale School of Management.

It was an internal training curriculum to learn the Apple way (unlike Amazon — with its 6-page memo writing culture — Apple’s organization is built around demos and

Apple University was one way to institutionalize Jobs’ approach).

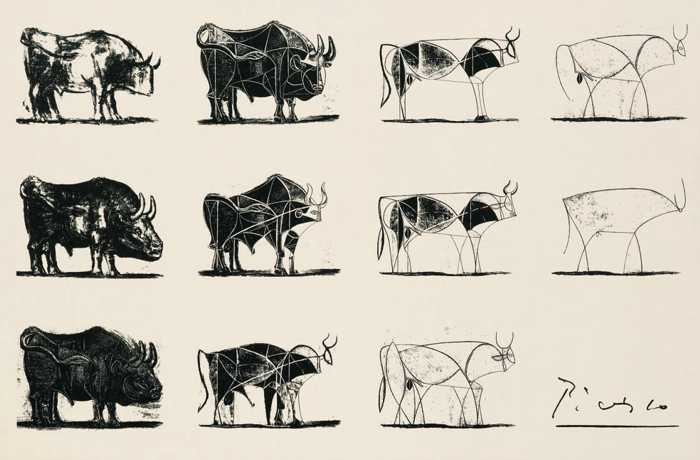

Ever secretive, Apple rarely shared the teachings outside of the company but it’s known that the University taught one of Jobs’ all-time favourite works of art: Pablo Picasso's “The Bull”.

Picasso created this series of 11 lithographs (stone prints) in December 1945.

With each successive print, a bull is simplified and abstracted.

Picasso's goal was to find "spirit of the beast".

Take a close look at the image and focus on the 1st, 4th and 11th prints as the bull progresses from:

a realistic drawing

with giant nutsto a deconstructed image with his famous "abstract" style

to lines outlining a shape

with smaller nuts

Through eleven iterations, Picasso simplified the image until it captured the "essence" of the bull.

"Two holes,” Picasso said of the abstraction process. “That’s the symbol for the face, enough to evoke it without representing it. But isn’t it strange that it can be done through such simple means? Whatever is most abstract may perhaps be the summit of reality.”

Jobs appropriated the line and said, “You have to deeply understand the essence of a product in order to be able to get rid of the parts that are not essential.”

Apple uses the evolution of its mouse as an example of Picasso’s philosophy at work (e.g., the buttons were "abstracted" away…although that upside-down mouse charging was a very unfortunate detour).

Remember when Apple was good at marketing before it launched those hot dog Genmoji billboards?

Specifically, recall that iconic “Think Different” ad campaign. Watch it until the end.

Yep, that’s Pay Me Picasso closing out the 1-minute video…and it’s a clip of him drawing a bull’s nuts.

Anyway, what does this have to do with Miyazaki?

As someone that has thumbed through a lot of film scripts for fun, I was (ignorantly) expecting that Miyazaki also wrote scripts for his projects and assumed the “essence” of his films would be a logline (aka the film’s big idea in a few words).

A lot of animated films do start with a script but Miyazaki actually starts his films with a single image (a notable director that does both is Ridley Scott, who draws elaborate storyboards — aka “RidleyGrams” — for his films).

In the documentary, Arakawa says that Miyazaki works without a script for “maximum creative freedom”. Miyazaki’s version of a script are image boards. These are the scenes of the films he passes on to his animators.

“Image boards test the boundaries of imagination in search of an entertaining picture,” explains Arakawa.

In his memoir, Steve Alpert relays a similar take on the Studio Ghibli process:

To begin a new project Miyazaki would allow images and ideas to percolate through his imagination, capturing them in drawings or watercolor sketches. Often he had ideas for two or three new films going at once.

He would amass the images he had drawn and begin to refine them and work out isolated plot lines to go with them. When he thought he had an idea for a new film, he would confer with his producer, Toshio Suzuki, and they would discuss the possibilities.

They would agree on an idea, tell other people in the studio about it, the people who heard about it would enthusiastically approve of it, and a week later the idea would be discarded in favor of another completely different idea. Eventually an idea would stick and the drawings for it became more fully rendered.

Other artists would be brought in to do concept art for the film. A formal decision would be reached and more artists would be hired to do background art, location hunting, and more concept art. One or two of Miyazaki’s more elaborate drawings would be chosen to represent the film, and the studio would announce the film. Production would begin, the theaters it would play in would be booked, and almost exactly two years later the final film would emerge.

Earlier, we discussed Miyazaki going through creative hell.

At one point, he pulls out a box of un-used pastels from his desk drawer. He uses them for the first time and starts drawing a scene. Turns out that the new drawing tool unlocked an idea in his mind.

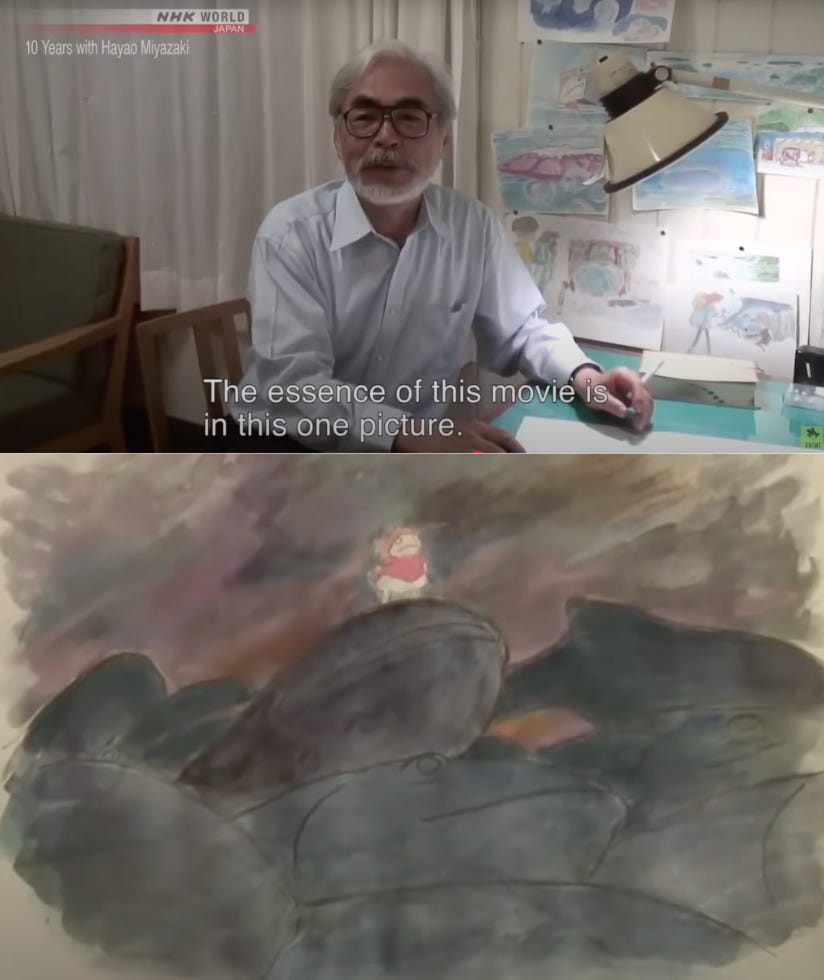

“The essence of this movie is in this picture,” Miyazaki says of a Ponyo sketch. “Finally, I’ve drawn the definitive image of this story.”

Two quick thoughts. First, Miyazaki uttering “essence” echoes Jobs talking about Picasso’s Bull. Second, Miyazaki defining his film through an image is definitely unique.

Even the team at Pixar — who watched Studio Ghibli films anytime they were stuck and once invited the Japanese master to their studio in California — relied on the written word as the basis of the story (Pixar co-founder John Lasseter on Miyazaki: “You know how when you’re watching a movie, you’ll say, ‘Wow, I’ve never seen that before’? With Studio Ghibli films, that happens in every sequence.”).

Think back to those scenes of Miyazaki struggling through the creative process. Well, he was grinding to get this one image.

To distill his idea and find the “essence” of the film.

The Importance of One Decider (Father vs. Son)

The beauty of 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki is that we get the entire Miyazaki experience.

He’s clearly a genius. Kind of wacky. Has some jokes. Often salty and gives his team members a hard time for not meeting his standards. But, also, he clearly cares about them.

Based on the documentary, the most glaring criticism to make of Miyazaki is that he’s a subpar father.

We discover his parental shortcoming by watching interactions with his eldest son Goro.

Goro was born when Studio Ghibli was just getting started in the mid-1980s and Hayao rarely saw his son. There’s a pretty heartbreaking scene in the documentary when Miyazaki says, “Because of the work and so on, I didn’t spend much time with [Goro]. Not that I was running away, but the result was the same. I owe that little boy an apology.”

Reflecting on his childhood, Goro says he didn’t want anything from his dad other than presence.

During the first episode of the documentary, Goro is directing his first film for Studio Ghibli (2006’s Tales from Earthsea).

We find that Hayao is not very supportive of his son’s effort and repeatedly says that Goro “isn’t ready”.

This is Hayao’s reaction after he abruptly walked out of a screening for Goro’s film.

Studio Ghibli’s main producer Suzuki has to mediate the relationship between father and son.

The younger Miyazaki actually didn’t want to follow in his father’s footsteps. Goro started his professional journey as an architect. He was pulled into the Studio Ghibli orbit after Suzuki asked him to help design a Ghibli museum.

Goro’s film Tales from Earthsea ends up as a box office success but has mixed reviews and critics say it falls short of Hayao’s work. I mean, yeah, no shit. What an impossible bar to meet.

Fast forward to the third episode of the documentary: Goro gets another shot at directing a Studio Ghibli film and we watch him work on 2010’s Tales From Poppy Hill.

Goro was so burnt by his father’s comments during the previous film that he asks producer Suzuki to keep Hayao away from the new film’s storyboard sessions.

“I hide [the storyboards] before I go home,” Goro says. “I don’t show him the storyboards. If [my dad] sees them, he’ll want to say something. I don’t want to waver. So I need to do it alone.”

Whenever Hayao walks into the office, Goro covers up his work. The son is afraid that his old man will critique the images.

However, the separation between father and son doesn’t really work.

“Goro doesn’t get it,” says Hayao before unloading on his son. “It’s OK for him to stop directing. I think he should, he isn’t cut out for it. ‘Wanting to do something’ doesn’t mean ‘being able to do something’. Directing isn’t an easy job. You must push yourself until your nose wants to bleed. And see what you create. Most people can’t do it.”

I’m fine with tough love. But there’s a mean streak to Hayao’s approach. He almost wishes his son to fail for not abiding by his direction. This compounds the fact that he was never around during Goro’s childhood. Goro even says he tried to understand how his father ticks through Hayao’s Studio Ghibli films.

Either way, Goro’s pride eventually gives way. The son can’t seem to crack the story and is convinced to let his father intervene.

Hayao isn’t trying to collaborate, though.

“I don’t want to be one of those father and son teams,” says the master. “I don’t mean to interfere, I just want him to tap my wisdom.”

Hayao ends up making a story recommendation for his son. Basically, Hayao wants the female protagonist to demonstrate initiative and “vigor” at the start of the film by putting away her bedding as part of her morning routine.

The note is communicated through producer Suzuki and undoes Goro’s creative logjam.

Hayao is a bit more optimistic that his son can finish the job but this is the most encouragement he can muster:

“[Goro] must lead the pack and give his all. He should be willing to die for it. He needs to finish it, no matter what. He has to do it for his own sake. Because he chose this path.”

Goro is sad but has come to accept his father’s approach:

“He feels alive only when he’s making film. I think he needs to keep fighting in order to live his life. That’s the only way for him. He can’t live any other way. It’s impossible. He can’t change now.”

My takeaway from this back-and-forth is the importance of having one decider on creative projects. The amount of ego, personality and idea-clashing is too much when there are strong-headed individuals involved.

And almost all creatives that actually care will be strong-headed about their tastes and opinions.

The problem with Hayao and Goro is that the son expects the father to meddle deeply in his work. Suzuki helps to smooth the process and allows Goro to keep the reins of the project.

When we see a productive creative relationship like Lennon and McCartney, I feel like it’s an exception that proves the rule of having one voice make the final decision. Even then, their partnership flamed out — somewhat acrimoniously — as their interests diverged.

On the family front, Hollywood has seen a fair share of siblings working together well.

But it’s still a tiny fraction of of all films and the most famous ones have all eventually tried going solo including the Coen Brothers (Fargo, The Big Lebowski, No Country For Old Men), the Wachowski siblings (The Matrix series) and the Farrelly Brothers (Dumb & Dumber, Kingpin, There’s Something About Mary).

We previously mentioned the creative process for the South Park duo. But Matt Stone himself has said that he plays a supporting role to Trey Parker.

Similarly, this is why Netflix’s co-CEO arrangement is such an anomaly in the business world.

The end result of Hayao and Goro’s cold war is that the son has to be the sole decider on how to finish Tales From Poppy Hill.

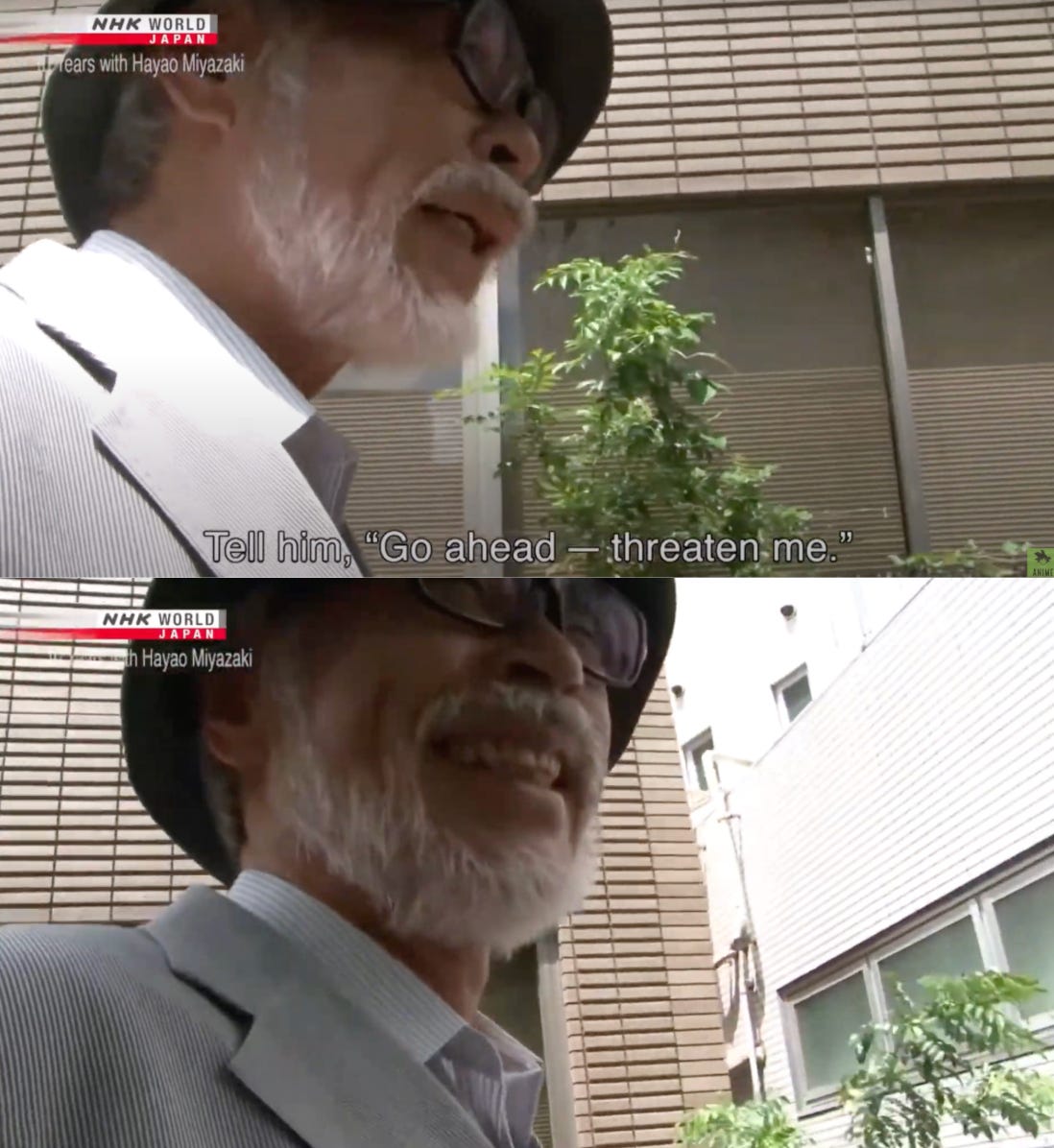

After the film’s internal screening, Hayao relents and gives his son a begrudging sign of respect. He tells to documentarian Arakawa to relay a message to Goro: “Go ahead and threaten me” by becoming better as a director and then he laughs.

When he’s told the line, Goro smiles and the Miyazakis clearly have a different way of showing affection:

Pros and Cons of a Mimetic Rivalry

The tension between Goro and Hayao reminded me of Rene Girard’s theory on mimetic desire. Girard wrote that humans desire what others desire, creating intense competition for the same objects.

Girard disciple Peter Thiel applied this insight at PayPal by assigning each employee a single non-overlapping task. This wasn't just about operational efficiency. It was a deliberate strategy to prevent mimetic rivalry. By eliminating role overlap, people could focus on the task at hand and worry less about politics. Worry less about splitting up resources or stepping on each other’s feet. Thiel’s approach short-circuited the mimetic cycle that often leads to conflict.

New parents know this phenomenon well: go watch kids play anywhere and they’ll always all descend on the same toy because another kids is playing with it.

Observing Goro in the documentary, it’s obvious his goal of making great animated films is modelled on his father’s career. He wants to achieve similar heights but to do so outside of Hayao’s shadow.

There’s a mimetic rivalry in Goro’s own head.

Goro hates it when people refer to him as “Hayao’s son” and it really pushes him to work harder.

Note how mimetic rivalry is not inherently good or bad.

It’s just important to realize what is motivating someone’s actions.

Hayao himself had a mimetic rival that pushed him to keep going and try to achieve greater heights.

In episode 4 of 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki, director Arakawa says that “someone is always at the back of [Hayao’s] mind”.

That person is Isao “Paku” Takahata. Six years older than Miyazaki, he co-founded Studio Ghibli but later made films outside of the studio, and “is the only rival that Miyazaki looks up to.”

In the early-2010s, Takahata hasn’t stopped making films. While the two co-founders “no longer exchange words of encouragement”, Miyazaki gets a “psychological boost” from “knowing that Takahata” is still going strong.

This rivalry is one reason why Miyazaki was even making the 2013 film The Wind Rises.

In 2018, Takahata passed away and Miyazaki gave the eulogy, sharing the first time they met and how the older director inspired him by refusing to let the film studio hamper his creative vision:

Paku-san, in those days, we were living with all of our might. You stood tall without bending to any hardships. This was an attitude we all shared. Thank you, Paku-san.

Throughout history, mimetic rivalries have pushed competitors to one-up each other:

Michelangelo vs. Leonardo da Vinci

Pablo Picasso vs. Henri Matisse

Steve Jobs vs. Bill Gates

Enzo Ferrari vs. Henry Ford.

Enzo Ferrari vs. Ferruccio Lamborghini

Marvel vs. DC

McDonald’s vs. Burger King vs. Wendy’sNike vs. Adidas

Whitney Houston vs. Mariah Carey

Tesla vs. Edison

Willem de Kooning vs. Jackson Pollock

Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier

Francis Ford Coppola vs. Steven Spielberg vs. George Lucas vs. Martin Scorsese

My all-time favourite is The Beatles and The Beach Boys. Paul McCartney said that Brian Wilson’s “God Only Knows” is the best song ever written. Famously, the Beach Boys album “Pet Sounds” inspired The Beatle’s “Sgt. Pepper”.

A pretty wild example is Floyd Mayweather hanging a giant painting of Conor McGregor in his house before their fight as a motivator.

By the early 1990s, Michael Jordan didn’t even have a true peer rival, so he was just inventing beefs out of thin air (while creating one of the greatest meme templates in the 2020s):

I’m not even saying if this is good or bad. It just is. Mimetic desire — wanting something because someone else wants it — is human nature.

Mimetic creative rivalries can obviously end badly. Think for a minute about “people fighting over the same prize” and you’ll come up with endless examples.

In Miyazaki’s case, he harnessed the drive to keep creating into his 80s.

Obsession With Detail

A commonality across great artists is the obsession with detail.

As Picasso said, “When art critics get together they talk about form, structure and meaning. When artists get together, they talk about where you can buy cheap turpentine.”

For any craft or creative pursuit, there are infinite small details that are equivalent to “cheap turpentine”.

In the case of Studio Ghibli, each film has 60,000 to 70,000 frames. Nearly all of them are hand-drawn and filled in with color paint. During the filmmaking process, Miyazaki looks at every single frame many times over. He’s making thousands of micro-decisions that are functionally equivalent to finding “cheap turpentine”.

“It adds to my understanding,” Miyazaki says of repeatedly looking over every frame. “Like, what facial expression this girl might have and when. Each piece adds up to the form of the characters. I slowly get to know each character while making a film.”

Two examples of his attention to detail stand out in 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki.

First, there’s a single 4-second clip of a crowd in the 2013 film The Wind Rises. It took his team 15 months — yes, FIFTEEN MONTHS!!! — to animate that single sequence.

We get to see Hayao work on a one character from the crowd; he re-draws someone’s back to make sure the tension and physics look just right.

After watching the completed scene during a group screening — again, after FIFTEEN MONTHS!!! — Miyazaki talks to one of his animators (Eiji Yamamori) and their exchange is unreal:

Miyazaki: “Good job.”

Yamamori: “It’s so short, though”

Miyazaki: “But it was worth it.”

Yamamori gets a few seconds of joy (he’s pumped) but has to move on to the next frame.

A second example of Miyazaki’s obsession with detail comes from the film Ponyo.

In one sequence, Miyazaki does a spot check on the work of another animator. He flips through the artwork and zooms in on the feet. They don’t look right. He pulls out an eraser. Re-draws the foot. Flips the animation. Re-draws it again. Erase. Draw. Again. Done.

“There’s a correct placement for those lines [on the feet],” he says while drawing. “If I can find them, I can show the ‘squeeze’ [of the foot]. It should spread and stretch out. Ponyo has never worn shoes. She’s squeezing him, so his jacket edge opens. And this part narrows. Squeeze, Squeeze.”

It’s thousands and thousands of these tiny changes that make a masterpiece.

There are many other examples in the documentary and every single one will make you think, “man, this dude is a beast.”

Final Thoughts

After Japan was struck by a devastating earthquake and tsunami in 2011, the Studio Ghibli staff gather at the office and decide to shut down operations for three days.

Miyazaki shows up mid-meeting and is not happy with the decision to pause work. The office is far from the epicentre of the earthquake and he says that countless other people — especially the emergency first responders — are still on the job.

“Why all the commotion?” he asks his team. “We’ve got to keep working. We can’t change the release date. We’re working hard to meet in. We must go on, even if it is hard. I think just leaving the production site is wrong. I can’t accept that at all. It’s precisely in times like this, that we must spin a myth. To show that we kept drawing despite any aftershocks.”

A few days later, Miyazaki holds a press conference and visits the worst-affected sites. He wants to cheer the children up. He knows that animation is not the most important job at the moment but it’s what he believes he can contribute.

For me, this sequence is the capper from 10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki.

You may not agree with everything that the legendary Japanese animator says or does — I clearly don’t in regards to his relationship with Goro — but this is someone so dedicated to his craft and it’s so clearly his chosen vessel to give something back to the world.

“Be true to your craft, without pretensions,” Miyazaki says in the first episode of the documentary. “Even though we are making a film — like it or not — a film is a reflection of its director. There’s no getting around that. Regret comes from having not made a film true to my heart.”

Driven by this belief, his creative process pushes him to his mental and physical limits.

But he also wouldn’t know what to do without film and animation.

“Most important things in life are a hassle,” he says in one moment of self reflection. “[But] if life’s hassles disappeared, you’d want the hassles back. When you’re not making a film, you miss doing it. You feel you can do it. But when you do [make the film], the burden becomes unbearable.”

Man, that is too real.

Hopefully, some of these Miyazaki quotes have inspired you to go create something (if not, try watching this David Goggins short video and at least you’ll get a 10km run from reading this article).

BONUS: Building Camaraderie

For all you Miyazaki die hards that made it this far, I know you’re probably wondering if I have thoughts on the 2024 Netflix documentary Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron (which covers the making of his last film).

I wanted to limit this piece just to “10 Years With Hayao Miyazaki” but, man, the Netflix Anime teaser for the film goes so hard with Miyazaki lines:

[Creativity is] not something I construct intellectually.

The brain lid opens.

Ideas rise to the surface from unknown places in the mind. I mean the most primitive brain. The ancient, reptile part. It’s very savage, but it’s usually under control.

You have to go crazy to open the inner doors of the brain.

It’s hard to return to normal life.

You stop caring about most things.

Finally, here’s a YouTube video of Hayao Miyazaki making ramen for his staff.

I’m not sure which documentary it is from but someone posted it on YouTube 16 years ago and the clip has 7m views with comments like “Once every few years I come back to this video just to watch Miyazaki make instant ramen. Something about it feels soothing.”

During Studio Ghibli’s weekslong sprint to finish a film, the team had a tradition for someone to cook dinner at 11pm and keep the team going.

Here is the master himself Hayao Miyazaki on cooking duty: he makes “Poor Man’s Ramen” by taking 10 bags of instant noodle then adds eggs, sautéed mushrooms and green onions.

Food gets smashed in seconds and he enjoys a dart before getting back to work.

Similar to everything we covered earlier in this peice, there is nothing glamorous about creativity as seen through the Miyazaki experience. It’s just grinding, grinding, grinding and more grinding.

As another YouTube commenter writes, “It’s depressing yet uplifting to think these masterpieces were made in ordinary office spaces.”

There are two other lesson I draw from the scene:

No job is too small: Miyazaki, the absolute legend, making instant ramen just shows that no job is below him when it comes to finishing a film.

The power of food: Making food for someone and breaking bread is one of the best ways to change the dynamic (usually positive) in a relationship.

On the latter point, I found a good articulation from Sir Jony Ive on how food can build camaraderie. He has people at his design firm LoveFrom cook for the team once a week.

Here is what the former Apple design chief told Patrick Collision:

Every Friday morning, I asked one person on the design team to make breakfast for the whole team.

We took turns and make things for each other.

I mean, we soared dizzy heights of some of the food and some of it was so shocking. But it all came from the same place in terms of motivation. […]

I was surprised at how powerful it was. It was a very powerful way…encouraging us in our practice to do good work and in building the team. I think there’s an interesting dynamic in terms of how we regard each other.

So, there it is. For maximum creativity, go make ramen and eggs for your team’s breakfast and tell them Hayao and Jony sent you.

PS. If you’re looking for other director deep dives, I also wrote:

Outstanding post, Trung. Thanks for sharing.

Wow! This is an amazing most. It's great to see you put so much effort into breaking down Miyazaki. Kudos!

I have to share this in my newsletter next week.

It always amazes me at how much effort goes into the work of creative geniuses.

It's motivating and scary at the same time. It makes me want to create, but I also question if I have the drive to put in that much work in to my craft.

Lots to think about here.