The $36B Nutella empire

The Ferrero Group is owned by Italy's richest family and built a $36B confectionary empire on Nutella, Ferrero Rocher, TicTac and more.

This issue is brought to you by Liona AI

Launch a GPT Wrapper in Minutes

As many of you SatPost readers may know, I’ve been building a research app for the past few years (Bearly AI).

Over that span, I’ve drank over 677 sugar-free Red Bulls while my co-founder built a flexible backend to manage all of the major AI APIs. We turned that backend into a product called Liona AI.

This easy-to-use platform lets your users and teams connect directly to OpenAI, Anthropic, Grok, Gemini, Llama, Cursor and more while you maintain complete control over security, billing, and usage limits.

Meet the Ferrero Group

This is Giovanni Ferrero.

He is Italy’s richest person, with a net worth of $36B.

The source of his wealth is Ferrero Group, the Italian confectionary giant which sold $14B of sweets last year (and is the world’s 2nd biggest candy maker). The private business employs 40k+ people and runs 30+ plants globally.

Nutella — the hazelnut spread — accounts for 1/5th of total sales (~$3B) but Ferrero also owns Kinder Surprise, Mon Cheri, TicTac, Crunch Bar, Nerds, Thornton’s and many more.

Halloween typically sells the most candy volume of the year but Easter is the Super Bowl for nicely-packaged confectionaries, which is right in Ferrero’s wheelhouse.

This wasn’t always the case, though.

The Origin

The OG Nutella was invented in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars. At the time, the famed French General started a continental blockade against his seafaring foes in the United Kingdom, which lead to a cocoa shortage across Europe.

Ever resourceful, Italian chefs started using ground hazelnut to stretch their dwindling chocolate supplies. The product they created was called gianduja, as detailed by First Versions.

Fast forward to 1946. Europe was dealing with yet another continent-wide shortage of cocoa (and food stuffs in general) following the end of World War II.

An Italian pastry chef by the name of Pietro Ferrero — a native of Alba, Italy — whipped out the recipe for gianduja and created a snack aimed at regular folk working on tight purse strings. His version of gianduja was sold as a solid block in gold foil, which was sliced like butter and eaten on bread. People loved it.

Why hazelnuts, though? Alba is in Italy’s northwestern region, where the nut (which comes from the hazel tree) is plentiful. Its high fat content and “nutty” flavor complements bitter chocolate very well (fun fact: a hazelnut’s shell-to-kernel weight ratio is a key quality metric).

In 1949, Pietro passed away. His brother continued to run the business while his son — Michele — joined the firm. Shortly after the changeover, the Ferrero clan turned the popular gianduja snack into a spread called Supercrema. According to Forbes, sales took off on the strength of “clever tricks”:

They sold it in receptacles like jars and pots so penny-pinched customers could reuse the containers. Rather than distribute it through wholesalers, the company used an army of sales reps who went directly to stores, helping keep prices low.

Michele took over in 1957 and the hazelnut product would have one final rebrand in 1964. That year, the Italian government started to crack down on superlatives in ads. Apparently, “super” was too hype of a word to have in a creamy-chocolatey product.

In response, Michele chose a new name that evoked the flavor of nuts. It literally could not be more literal: Nutella. With business going well, the Ferrero Group matched the name change with a reformulated product that added more sugar and cocoa (AKA made it a lot more addictive).

Michele Ferrero takes the business to new heights

Michele was far from a one-trick pony. He was a real-life Willy Wonka who was addicted to the game (of inventing new snacks). The Ferrero scion spent days on end taste-testing new candy formulations, all while sporting a lab coat.

His efforts yielded a caloric explosion of dopamine-inducing sweets:

Mon Cheri (1956): A cherry-liquor filled chocolate. Michele created a method whereby the chocolate would *not* absorb the liquor filling. It was a huge hit in Germany. (I’m pretty meh on these tbh).

TicTac (1969): These little oval mints were apparently named after the sound of opening and closing the container (it’s def smart: the click sound is a psychological hack that creates a “Pavlov’s Dog” type of association with the mint).

Kinder Surprise (1974): Michele wanted children to experience Easter everyday, so he create a toy-in-chocolate eggs (somewhat crazily, Ferrero is the world’s 3rd biggest toymaker).

As he was ripping off one invention after another, competitors tried to uncover Michele’s methods. But he went to great measures to protect the proverbial secret sauce.

The Alba factory was mostly closed to outsiders while employees came from multiple generations of the same family who were all super loyal to Michele (when he took over Ferrero in 1957, he told the workers: “I will not rest until I have secured a safe and peaceful future for your children.”)

And a select few of these workers have the incredible role as taste tester. Per Daily Mail, the job qualifications are no joke:

To be selected they must correctly identify the flavours of sweet, bitter, salty and umami… In another fiendish test, citric acid, kitchen salt, sugar and caffeine are dissolved in water. The tasters must then be able to place them in order of greatest concentration.

Women between 25 and 40 are best, although pregnant women are the most sensitive to taste. Candidates are then tested with raw materials such as milk, to see if they can identify the one that is less fresh.

Michele’s greatest technical achievement is the immortal Ferrero Rocher. Launched in 1982, he spent 5 years perfecting the praline (a spherical wafer filled with hazelnut and covered by chocolate…and more hazelnuts).

Who can forget that packaging? The gold foil with a paper basket. As Apple’s Jony Ive once said about the iPhone case: “I love the process of unpacking something. You design a ritual of unpacking to make the product feel special. Packaging can be theater.”

For Ferrero, that theatre happens once a year around Christmas. The firm sells 1/3rd of its annual supply of Ferrero Rocher during the year-end holiday. In the lead-up to December 25th, the Alba factory makes 900 pralines a minute (running 24/7).

The inspiration for Ferrero Rocher also adds to the story. Apparently, Michele designed it after the “the Roc de Massabielle, a craggy rock grotto at Lourdes which he visited every year on pilgrimage.”

In the only interview he ever gave — which was published after his death — Michele says all of his inventions targeted one customer archetype. Per the Financial Times, this archetype was a hypothetical Italian woman named “Valeria”:

“I think only of Valeria. [She] is the mother who does the shopping, the grandmother, the aunt, the consumer who decides what to buy every day.”

By the mid-1980s, Valeria was buying a lot of Nutella and Ferrero was a humming global operation with sales passing the $1B mark.

Preparing the next generation

Just as the business was passed to him, Michele prepared his sons — Pietro and Giovanni — to take over the Italian firm. It began at a young age. In one legendary test, Michele blindfolded his sons and they had to smell their way out of the factory.

Over the decades, the sons worked at Ferrero in different roles across the globe before becoming co-CEOs in 1997 (Pietro was 34, Giovanni was 33). By then, the Ferrero empire was bringing in $5B a year.

The transition was going as planned but tragedy struck in the 2010s:

2011: Pietro died of a heart attack while biking in South Africa (he was only 47)

2015: Michele died at his home in Monaco (he was 89); thousands attend his funeral in Alba

After Michele’s death, the future of Ferrero Group was in question. For decades, the firm was bombarded by takeover offers but Michele always said “no, not for sale”. He was old school and long refused debt and shunned acquisitions. Italian financiers considered him un-bankable.

Giovanni’s ~$6B bet

After his father’s death, Giovanni took full control of the business and made clear that Ferrero Group wasn’t going anywhere. With a healthy profit margin of 10%, Ferrero had been stacking cash for years.

Giovanni believed that the confectionary industry was headed for the same type of consolidation as the beer industry where 4 firms (AB InBev, Constellation Brands Inc., Heineken, MillerCoors) own 86% of the market.

Per Giovanni, “someone will emerge as a front-runner” in the confectionary field. Why not Ferrero?

Since 2015, Giovanni has spent ~$6B on chocolate, candy and snack brands. One major goal has been to expand Ferrero’s footprint in the US and UK:

Thorntons for $177m (2015): An iconic UK chocolate brand (with all physical stores shut down since the pandemic).

Fannie May for $115m (2017): The American chocolate maker was acquired from 1-800-Flowers.

Ferrara Candy for $1.3B (2017): Acquired from PE firm L Catterton.

Nestle’s US candy business for $2.8B (2018): The Swiss consumer giant actually tried to acquire Ferrero Group but was rebuffed. In the end, Ferrero acquired Nestle’s classic American brands like Baby Ruth, Butterfinger and Crunch.

Kellogg’s Snacks for $1.3B (2019): Another acquisition of popular US snacks including Keebler, Famous Amos, Mother’s and Murray and Little Brownie Bakers.

Burton’s Biscuit’s for $426m (2021): The deal included Maryland Cookies, Jammie Dodgers and Wagon Wheels.

Among Ferrero purists, the acquisitions have been polarizing for two reasons:

Lower end: The acquired products (eg. Crunch, Butterfinger) are “lower end” compared to Ferrero’s homegrown products. These new product lines can hurt the firm’s margins.

Less healthy: As competing snack giants go healthier, Ferrero is doubling down on sugary vices.

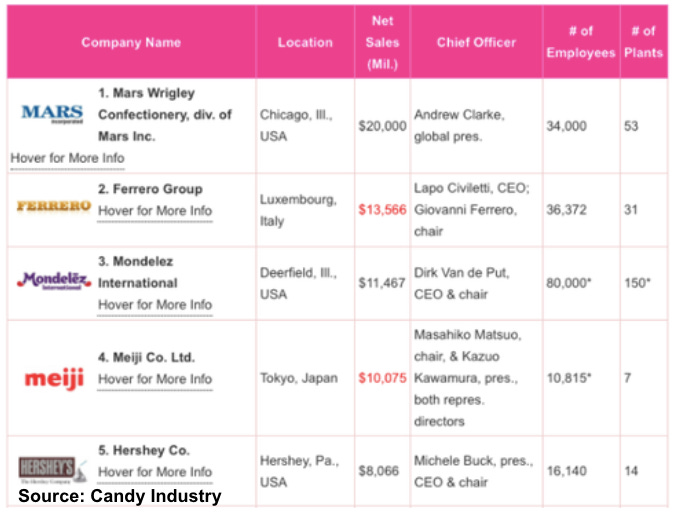

Among confectionary giants, Ferrero only trails Mars, which sells $20B a year of well-known brands including Mars, Snickers, Twix, Skittles and M&Ms. Ferrero ($14B) leads Mondelez ($11B), Meiji ($10B), Hersey ($8B) and Nestle ($8B).

Challenges moving forward

At its size, Ferrero Group is the world’s largest buyer of hazelnuts (1/3rd of the world’s annual supply). To secure its supply of the crucial input, the firm even acquired a hazelnut factory in Turkey in 2014.

However, its management of the crop is a huge source of controversy: hazelnut gathering is backbreaking work and 70%+ of production comes from Turkey, where there are charges of child labor (often Kurdish migrants).

The Nutella maker says it wants 100% hazelnut “traceability”, but supply chain complexity makes this goal difficult (it faces similar criticism for palm oil sourcing). To help achieve its traceability goals, Ferrero bought 2 of the largest hazelnuts traders and is now the world’s #1 hazelnut *supplier* (as well as buyer).

Ferrero also faces questions over the high sugar content of Nutella. For decades, it advertised the spread as a part of a “balanced breakfast”. Spoiler alert: it’s not that healthy (you can put the spoon down now). In 2013, Ferrero paid $3m to settle a California false advertising lawsuit related to the claim.

Aside from managing these difficult issues, Giovanni — who gave up the CEO seat and is now Chairman — says Ferrero Group is aiming for +7% growth a year (per the rule of 72, sales would double in 10 years). It’s too early to tell if Ferrero’s aggressive M&A will get it there.

Amidst the acquisition spree, Giovanni hasn’t forgotten Ferrero’s roots. The firm is (kind of) back to inventing: in 2021, Ferrero unveiled its first ever ice cream stick and chocolate bar.

Other Sources: Reuters, Bloomberg, Candy Industry, First Versions.