"The Economist" Cover Curse, Explained

PLUS: My Dune 2 review, TikTok Ban and Why Jalapeños Are Less Spicy.

Hey, thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about The Economist and how the magazine’s cover is perceived as a contrarian investing signal.

Also this week:

My Dune 2 review

TikTok might actually get banned now

…and those fire memes (including Sydney Sweeney)

The Economist’s magazine cover from last week stirred up some buzz in finance and investing social chatter.

It featured a photo of a bull being carried by balloons with the headline “How High Can Markets Go”. The cover suggests that the current stock market bull rally may be running out of steam.

Over the years, The Economist has gained a reputation as a “contrarian indicator”.

What does that actually mean? Well, the weekly publication — which was founded in 1843 — is read by basically every manager, executive and decision-maker in the business and political worlds.

By the time an idea is mainstream and important enough to make the cover of The Economist, all of the upside from an investing standpoint has probably been squeezed out (this is related to the stock-picking aphorism that states “buy the rumor, but sell the news”).

We will walk through some famous examples of The Economist cover calling a top or bottom later in this article. But first, let’s talk about the magazine’s appeal and how it helps to form consensus.

The Economist’s Appeal

I am a big fan of The Economist and the publication’s app is one of my most-visited smartphone destinations. There are nearly 1.2 million other subscribers who share this same affinity and here are a few reasons:

Curator-in-Chief

Publishing in One Voice

Corporate Social Proof

So Many Puns

***

1. Curator-in-Chief

There is too much content in the world.

The internet and the rise of digital-publishing tools for anyone who wants to create — YouTube, social media, newsletter platforms, LinkedIn etc. — mean that media options are infinite.

What happens in a world of infinite content? According to tech analyst Ben Thompson, “in a digital economy, limitless supply means that users gain value from discovery and curation.”

The Economist is a top-tier curator of relevant news and ideas for decision-makers in politics, business, finance, culture, media and science. Its job every week is to comb through all the relevant topics and condense them into ~100 pages of font 9 text, which is equivalent to 50,000k words (or a short novel).

The official mission is to “inspire progress globally” and the About Us page for The Economist Group — The Economist’s parent company — states:

From its beginnings in 1843, when The Economist newspaper was founded by a Scottish hat manufacturer to further the cause of free trade, The Economist Group has evolved into a staunchly independent global media and information-services company with intelligent brands for an international audience.

Over time, the newspaper has helped readers grasp the great drivers of change, from technology to geopolitics, finance and economics. It added a dedicated section on the United States in 1942 and a China section in 2012. It expanded successfully into North America, which became its largest market. To serve decision-makers in businesses and beyond, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) became a leader in country analysis and forecasting. Live events around the world brought global thought-leaders together to discuss critical topics at roundtables and summits.

There are obviously other notable publications that help inform elite consensus including The New York Times (founded in 1851), The Financial Times (1888), Wall Street Journal (1889), Barron’s (1921) and Bloomberg News (1990). However, when it comes to keeping up with the news for busy business people on a weekly cadence, The Economist is older than the rest and relies on its 181-year history to provide an authoritative perspective.

Seriously though, The Economist never stops reminding you that it has been around since 1843. It even named its sister magazine 1843 to let us know that important people have been reading it since…1843.

***

2. Publishing in One Voice

One way the magazine maintains a historical through-line to its 1843 founding is by keeping each reporter anonymous — there are no bylines — and publishing all articles as The Economist.

In this excerpt, the magazine explains why it adopted this philosophy:

Historically, many publications printed articles without bylines or under pseudonyms—a subject worthy of a forthcoming explainer of its own—to give individual writers the freedom to assume different voices and to enable early newspapers to give the impression that their editorial teams were larger than they really were. The first few issues of The Economist were, in fact, written almost entirely by James Wilson, the founding editor, though he wrote in the first-person plural.

But having started off as a way for one person to give the impression of being many, anonymity has since come to serve the opposite function at The Economist: it allows many writers to speak with a collective voice. Leaders are discussed and debated each week in meetings that are open to all members of the editorial staff. Journalists often co-operate on articles. And some articles are heavily edited. Accordingly, articles are often the work of The Economist’s hive mind, rather than of a single author. The main reason for anonymity, however, is a belief that what is written is more important than who writes it.

In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, our editor from 1938 to 1956, anonymity keeps the editor “not the master but the servant of something far greater than himself…it gives to the paper an astonishing momentum of thought and principle.”

The collective voice is globally-focused, pro-free market, politically centrist and largely supportive of technological innovations (while I enjoy the Technology Quarterly issues, it is a bit annoying how often the magazine reminds readers that it was founded in opposition to protectionist UK Corn Laws from the early 19th century).

There is an elite air to the publication and the attributes I described in the previous paragraph scream “Davos Man”. But that typically doesn’t come through in the text.

Example: The Economist provides seemingly obvious descriptions such as “McKinsey, a consultancy” or “Goldman Sachs, a bank”. I assume everyone reading would know these things but maybe they don’t. And the way that the publication consistently includes the phrases signals that it is a single general voice writing to any interested reader (rather than just industry insiders writing for other industry insiders).

While an article’s authorship is anonymous, veteran readers of The Economist will be familiar with the publication’s various editorial columns within different sections of the magazine (e.g. Lexington in the USA section).

Once a writer is assigned to these editorial sections, he or she is able to maintain a semblance of a unique voice for a period. According to The Economist, here is a “fun-fact” rundown of the etymology behind these names:

Bagehot (in the UK section): Walter Bagehot was a UK politician and edited The Economist from 1861-1877.

Lexington (in the USA section): Name of the town where the first battle of the American Revolution took place.

Banyan (in the Asia section): A type of tree under which Gujarati merchants conducted business.

Schumpeter (in the Business section): The Austrian economist famous for “Creative Destruction”.

Buttonwood (in the Finance section): The tree on Wall Street under which the establishment of the New York Stock Exchange was signed in 1792.

***

3. Corporate Social Proof

Even if the coverage and “collective single voice” approach is not for you, Game Theory suggests that you should read The Economist anyways. The magazine has built so much elite mind-share in business and politics that most time-strapped “decision makers” probably just assume that other time-strapped “decision makers” are reading it.

With that expectation, the topics in The Economist serve as a quasi-shared knowledge base.

It has become one of the weirdest business hotel flexes, too. I can't count how many times I have seen someone in the lobby — or on the recumbent bike at the hotel gym — holding the magazine at shoulder height to show the world that they are downloading the hottest consensus takes.

Succession has an incredible scene that showcases this phenomenon. In one of the final episodes of the classic HBO show — which is a lampooning of elite media, business, and politics — the goofiest character (Cousin Greg) embarrasses himself in front of a Big Tech CEO by saying, "I read a great article recently in The Economist about this," while discussing a topic he clearly knows nothing about.

As one insightful dude on Quora (cynically) explained: “Welcome to The Economist: a consensus publication on things most people don’t understand that is great because everyone thinks it’s great.“

Social proof at its finest!

Speaking of social proof, The Economist is not shy about plugging the fact that “those in the know” read it. This was perfectly illustrated by two famous ad campaigns the magazine previously ran.

A TV ad from 1996 shows the late former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger flying coach while sitting next to a suspender-wearing business putz. A remake of the ad from 2015 stars former Google CEO Eric Schmidt stepping into an elevator next to some other tight-fisted business putz.

The schtick of these ads is to put the viewer in the position of the business putz sitting in coach next to Kissinger or the younger business putz standing in the elevator next to Schmidt. In these scenarios, you’re probably thinking: “if you could chat with one of the 50 most powerful people in the world, what would you talk about?” Clearly, if you want to have conversational fodder, you better read The Economist.

Whether or not you buy the hype, The Economist magazine has created a powerful halo for The Economist Group and driven business results:

Employees: Over 1,600 people working for The Economist (weekly publication), 1843 (lifestyle magazine), Economist Impact (consulting & events) and Economist Intelligence Unit (business intelligence). The Economist itself has over 300 editorial staff.

Influential owners: Exor (holdco for Agnelli family, which owns Ferrari, Chrysler, Fiat etc) owns 43% while the Rothschilds family owns 21%.

Subscribers: 1.2m subs paying $200+ a year (the magazine has been hovering at this subscriber level for the past three years and maybe this is a ceiling)

2023 sales: $480m (55% attributed to The Economist magazine)

2023 operating profit: $53m

I got into The Economist while living in Vietnam in the late-2000s. I had no real corporate need to read the magazine — because I was a 20-something partying 4x a week, subsisting on $0.50 street pho and confusing my parents as to why they fled Vietnam only to see their idiot son go back — but it gave me comfort that I was keeping up with the world.

Also: Kissinger and Schmidt both had their own, errr, separate connections to Vietnam, so I just wanted to make sure I had some talking points ready in case we ever crossed paths.

***

4. So Many Puns

Staying informed about the world in an efficient manner and looking smart on recumbent bikes are important life skills.

However, The Economist truly delivers with its bounty of puns. In fact, The Economist holds the title for my personal favorite magazine pun of all time. The gag is from an article about the IVF industry and companies that lend money for people who need to pay sperm banks for fertility services.

The subtitle (in red below) reads “Seed Capital”.

SEED CAPITAL!!!!!!!!!!

Come on! That is incredible.

If the pun didn’t make you chuckle, please read the following exchange:

You: Eh, not funny.

Me: It’s an article about the sperm bank business!

You: Yeah, I get that, it’s still not funny.

Me: Are we looking at the same thing? The header says “seed capital”.

You: Yes, I get that. The article is talking about the business of sperm banks. “Seed capital” is just a form of early investment for these businesses.

Me: Bruh! Just focus on the word “seed”.

You: Nah..still nothing.

Me: It’s a PUN! Seed like sperm or little swimming dudes trying to fertilize ova.

You: Puns are for kids.

Me: Fair enough.

There are dozens of solid puns in each issue and — as the tweet below shows — The Economist doesn’t mind tooting its own horn:

A Contrarian Indicator

Now that we’ve established The Economist’s role in consensus making — and my affinity for dad jokes — let’s talk about the magazine cover as a contrarian indicator.

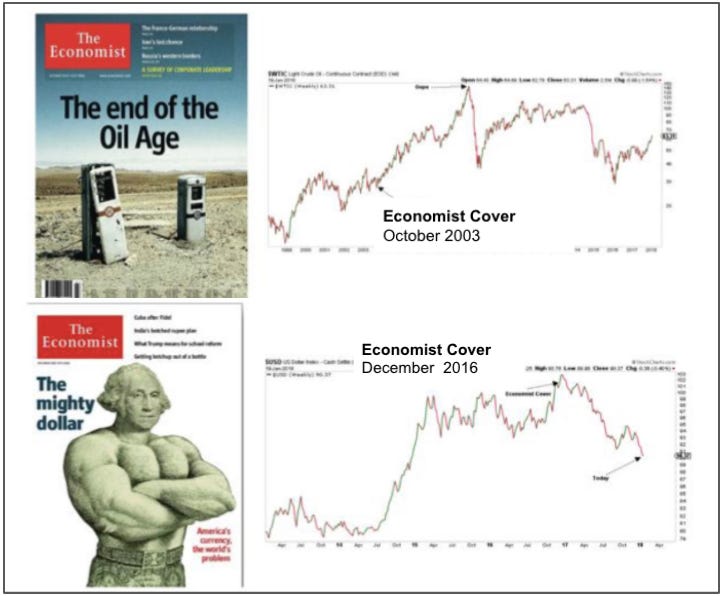

In 2018, HFI Research published an article analyzing some notable headlines from previous covers of The Economist (and matched up the date with the related price charts).

I’ll point out two notable examples:

Bottom of Oil: An October 2003 cover headline read “The end of the Oil Age” before WTI Crude went on a multi-year rally.

Top of US Dollar: A December 2016 headline read "The Almighty Dollar" and preceded a year-long fall in the US currency.

Obviously, there are flaws in this contrarian indicator. It is not clear what period of time the asset is being measured on. Also, there have been many instances when the cover hasn’t been a contrarian indicator at all.

Take another cover flagged by HFI Research titled “The New Titans”, which was about the power of Google, Amazon and Facebook. The combined market cap at the time was ~$1.8T and has consistently risen in the past 6 years to a total value of ~$4.8T.

In other words: it’s easy to cherry-pick covers.

No sophisticated investor is basing their investment decisions solely on The Economist cover (I hope not). Nor is The Economist cover even meant to be investment advice. Remember, the mission is to “help readers grasp the great drivers of change” and that is a long-term perspective.

Having said that, these covers still point at “what is the median business and political person thinking about” and can certainly be a signal for any due diligence.

Since 2018, there have been a few other contrarian covers that I have found:

October 10, 2019 “Inflation is losing its meaning as an economic indicator”: COVID was obviously a tail event but damn this was a rough call.

September 18, 2021 “The promise and perils of DeFi”: Oh man, anyone who bought Ethereum (ETH) after this cover got bodied. Within a year, ETH was down 60% ($3k to $1.4k).

Nov 19, 2022 “Crypto’s Downfall”: About 14 months after the previous cover, The Economist reported on FTX/SBF and called crypto's demise. Bitcoin (BTC) doubled over the next year ($17k to $35k).

Most mainstream publications guffed these stories but getting singled out comes with the territory as a consensus-maker.

Final Thoughts

Any fan of American Football has been reading this and thought "sounds a lot like the Madden Curse." For those unfamiliar, the “Madden Curse” is the belief that any NFL player featured on the cover of the EA Madden video game will experience a setback in the following season, whether it be due to an injury or poor team/individual performance (according to CBS Sports, 60% of players on the cover have experienced a "curse" since 1999).

However, the only reason anyone cares about the Madden cover is because it is one of the best and most successful sports gaming franchises ever. You can’t be a “curse” — or contrarian signal — if you are irrelevant and no one cares about you (to wit: there isn’t a SatPost contrarian investment indicator but you would actually be wise to do the opposite of any advice I ever give).

I joke about The Economist’s obsession with its 1843 founding but the publication has been the go-to source for news analysis among top-tier business — and political — folks for nearly two centuries.

Corporate managers read The Economist because their managers read it because their managers read it. As mentioned earlier: The Economist is a quasi-shared knowledge base among this type of reader. For sure, the magazine has also adapted to the times with strong digital products (e.g. app, newsletters) but the brand is a moat that up-and-coming media challengers have not been able to crack for decades.

Back to last week’s cover on the current stock market bull run: go jump on a recumbent bike and read the article for some interesting analysis.

Just don’t put too much stock in the cover as a contrarian indicator (pun intended).

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email.

If you press this blue button below, you can save hours of work with AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Links and Memes

My Dune 2 Review: After I wrote last week that I hadn’t seen Dune 1 (2021), a bunch of you replied and said I was a fool and needed to buckle up. So, I watched it on Sunday and then took my wife on a dinner date night on Thursday to watch the sequel. We went to one of those VIP theatres that serves alcohol, so everything I’m about to write is clouded by the fact that I enjoyed it while multiple White Claws deep.

It was very entertaining with the caveat that my main measure for film quality now is “can I sit down for 90+ minutes without the urge to look at my phone and this better be worth getting a nanny for the kid”. Oppenheimer — which is about to sweep the Oscar’s — passed the test last year. And Dune 2 had me rapt for 2.5 hours (however, I did have the urge to go to bathroom after the 3rd White Claw and missed some of the movie…that was a miscalculation).

I think that watching both films back-to-back in one week made me enjoy the production way more. Many reviews for Dune 1 felt that there was too much set-up and not enough action. The reason is because director Denis Villeneuve split the first Dune book into two parts (with no guarantee of a 2nd film).

Warner Bros. did not greenlight the sequel until the box office results for Dune 1's first week came in. There have been two previous major adaptations of Frank Herbert's 1965 sci-fi epic: a 1984 David Lynch film and a 2000 TV series. Adapting the sprawling book with a fully-realized, spice-filled galactic civilization was always a challenge. That's why Villeneuve decided to make two films from the start, and it paid off. However, if he didn’t get the second film, the first one concludes on an open-ended note with a character saying “this is only the beginning”…which would be weird if that was the end (I totally understand why some people were annoyed while watching the first one without knowing that a sequel was coming).

My fave part of Dune 2 was the unreal visuals. It’s a gorgeous movie. I should have done iMax. I also like Zendaya and Timothee Chalamet as leads because we can’t keep having 60-year old Tom Cruise be the main draw and need new blood. Chalamet is being called the new Leo and he is magnetic (my wife can’t stop talking about his square jawline). Leo did give Chalamet acting advice and said “no superhero movies and no hard drugs”. Dune is close-ish to a super-hero movie but Chalamet is on the right Leo track (although no young actor will ever have the same hype as 23-year old Leo after Titanic).

Quick sidebar: Villeneuve is French-Canadian (let's effin' go Canada) and has directed two other unreal sci-fi flicks (Arrival, Blade Runner 2049) and one of the hardest action movies ever (Sicario).

Villeneuve will now complete a Dune trilogy and has a chance at joining other epic trilogy staples such as the original Star Wars, Lord of the Rings and Christian Bale’s Batman. The second film in these series — Empire Strikes Back, Two Towers, Dark Knight — were my favourites. Once you establish the world with the first film, the sequel gets to truly raise the stakes for the finale. Dune 2 hit all the sequel notes for me except the last 30 minutes. Villeneuve did a respectable job compressing the book into ~5 total hours of film but turbo’d the end of Dune 2 trying to tie off too many storylines.

Either way, one superweapon that Villeneuve has is Hans Zimmer, the legendary composer who first read Herbert’s Dune when he was 14 years old in 1971.

Long a fan of the book, he jumped at the opportunity to work with Villeneuve on Dune 1. This was their approach, per a Vanity Fair video profile:

No classical music: The sci-fi films that Zimmer saw growing up (2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Trek, Star Wars) had classical European orchestras, which made no sense to him since the settings were in different times and places (European orchestras didn’t fit with the fictional desert planet of Arrakis).

Human vocals: Much of the soundtrack is centered around chants and vocals, as Zimmer believes that the human voice would remain constant in future civilizations.

Different instruments: Zimmer worked with musicians to create new sounds from lesser-known instruments (e.g. Armenian Duduk flute) or invented entirely new contraptions (eg. a specially cut PVC pipe for desert wind). Relatedly, Villeneuve invented a language for Dune 2.

Zimmer wanted to score Dune so badly with Villeneuve that he passed on scoring Oppenheimer for Christopher Nolan (they had previously worked on 6 films together including the Dark Knight trilogy, Dunkirk, Inception and Interstellar).

Do you know how good you have to be at your job to be able to turn down Nolan?

Zimmer’s Dune 1 soundtrack won the Oscar for Best Original Score (it was his second win after 1994’s The Lion King). The Dune 2 score is literally hot fire and Villeneuve has already given Zimmer material to start on the Dune 3 soundtrack.

PS. Check out this glorious video of someone rolling up to the Dune 2 premier in full cosplay and a motorized sandworm.

***

Why are jalapeños less spicy? It’s not your imagination. according to D Magazine, Jalapeño peppers are less spicy in North America and we have Big Agriculture to blame:

60% of jalapeños go to processing plants (canning, salsa, creams etc.) while 20% are smoke-dried and only 20% are sold fresh.

Major processors have the most influence and sell products at different heat levels (mild, medium, hot). Therefore, they prefer jalapeños to be non-spicy and separately add capsicum extract to achieve the desired heat level.

Pepper farmers cater to the demands of Big Ag processors by growing non-spicy plants.

Makes sense but I still feel violated!

***

TikTok might actually get banned this time. Last week, a US House committee unanimously passed a bi-partisan bill aimed at banning TikTok or forcing a sale away from its China-based owner ByteDance. If it gets to the President's desk to sign, ByteDance would have 6 months to sell or have it shut down. Nate Silver explains why there is so much momentum behind the ban.

The TLDR is that TikTok doesn’t have natural support from either party. Republican voters largely agree it’s a national security threat and Democratic voters are weary of misinformation. My take has always been straightforward: 1) China bans foreign social media and — on trade grounds — it’s an easy argument to do the same; and 2) it would be unthinkable for the USSR to have owned one of the Big 3 TV Networks (ABC, CBS, NBC) in the 20th century and that’s what is happening now in terms of a major media channel that influences public opinion.

TikTok fumbled its response to the bill. It tried to pull the 1st Amendment “Free Speech” card (reminder: it is owned by a Chinese company that has given a board seat to the CCP). Then, it blasted a notification to TikTok users to call Congress. A bunch of 12-year olds that can’t vote bombarded Congressional phone lines. If the US government is concerned about your app being a source of foreign influence, the notification to 150m American users is probably even more justification for the Bill in the eye’s of the legislators.

And them fire X posts/memes:

We need intermissions reinstated for movies longer than 2.5 hours. The urination anxiety is real.

Good article. Here’s a more empirical look.

https://medium.com/@mbrentdonnelly/a-somewhat-empirical-look-at-the-magazine-cover-indicator-2d0ca835f7d1

Scroll down here for out of sample performance after I wrote that article

https://x.com/donnelly_brent/status/1745867570127814876?s=46&t=Z-boW5UHRWKGTmYteOnSkA