The Michelin Guide business, explained

PLUS: Did people in the past "look" older?

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, I’ll be writing about the wild Michelin Guide business.

This issue of SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Do you spend hours a day reading and writing?

I do. To help manage the content deluge, I created an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI to boost:

Reading (instant summaries)

Writing (editing, rewording, auto-generated text)

Image generation (via DALL-E or Stable Diffusion)

The best part: the tools fit into any work flow with a quick keyboard shortcut (via desktop app, chrome extension or browser).

Michelin

So, I had my first Michelin dining experience a few weeks ago.

It was at a restaurant called Mugaritz, about 20 minutes outside of San Sebastien, Spain.

The stop was part of a 3-week trip I took to Europe with my wife and son. As it was summer in the Mediterranean, I packed very light for vacation (translation: one pair of sandals and lots of shorts).

On the night we rolled up to Mugaritz, everyone was dressed to the 9s while my dumbass was wearing board shorts and flip flops for a 21-course meal with wine pairing.

Fortunately, I redeemed myself by reading thousands and thousands of words about the Michelin Guide business and will share answers to the following questions:

How did Michelin Guide start?

What is Michelin Guide’s secret sauce?

What is the Michelin Guide business model?

Why have some chefs given back their Michelin stars?

How did Michelin Guide start?

The Michelin Guide origin story is pretty well known.

In 1889, André and Edouard Michelin founded a tire company in Clermont-Ferrand, France. At a Paris Exposition in 1900, the pair launched a guidebook for hotels to give car owners in France — of which there were less than 3k — places to travel on the continent (more destinations = more driving = more tire sales).

Independently-reviewed restaurants were added to the guide in 1920 and the first star was awarded in 1926. The current 3-star ranking system was first published in 1936. The Guide didn’t come to America until 2005 followed by Japan in 2007 (with later additions in South America and Asia).

Some ballpark numbers:

Total #: ~3200 Michelin restaurants in 30 countries (>600 in France, >400 in Japan, >300 Italy)

Star distribution: 1 star (2640), 2 stars (417), 3 stars (143)

The majority of Michelin restaurants (>80%) have 1 star. Any type of restaurant can qualify for 1 star (even street food). However, the jump to 2 stars is quite significant and requires top-notch service and experience.

The 3-star restaurants are found primarily in France (30), Japan (30), US (13), Italy (11) and Spain (11)

Average cost for a 2-star meal is $252 and a 3-star meal is $357

While the Guide loses money, the parent company benefits in other ways. The brand equity and cultural cachet — especially in food-crazy France — is worth a ALOT.

In the parent company filings, the Guide business is bucketed under “Michelin Experiences”, which covers fine dining, hospitality and travel. Here is how Michelin describes the segment:

“Michelin Experience remains an unrivalled vehicle for promoting MICHELIN brand and its premium positioning”

On the money side, one study estimates that the Michelin Guide’s entry into a country increases Michelin tire sales by 3% in that country. And Michelin does ~$25B a year in sales, so every basis point moves the needle (a theory on why Japan has so many 3-star restaurants is that Michelin wants to curry favor in the country to score car manufacturing contracts).

Speaking of new countries, Michelin will be releasing a Canada Guide in the Fall and just announced that it will review restaurants in Vancouver. If you work for Michelin and are reading this, I know a very good Banh Mi shop you should hit up (side note: my fave sub-genre of popular Korean dish is Korean Fried Chicken, which is in at least 5 Michelin restaurants).

What is the Michelin Guide’s secret sauce?

Signaling.

A 2016 study from Bocconi University makes the point well. In a smart set-up, researchers tracked how restaurant menus changed in Washington, DC before and after the launch of a Michelin Guide for the city.

Here’s the key excerpt:

“Rankings act as essential signals indicating competitiveness of organizations, which are typically prevalent in industries characterized by uncertainty in the assessment of quality”

By providing a benchmark for “uncertainty in the assessment of quality”, Michelin has been able to turn its brand from aggregator (of hotels, restaurants) to curator and tastemaker (of the best dining experiences).

In a comparison between DC restaurants that made and did not make the Guide, the study found the former group increased pricing to signal its new status and revamped the menu language to include more fancy cooking techniques (eg. “souvide”) and higher-quality sounding ingredients (it’s not clear if the menus actually changed).

Restaurants are willing to play the game because the exposure is great for business. Legendary chef Joël Robuchon — who was awarded a record 32 Michelin stars in his life — explained:

"With one Michelin star, you get about 20% more business. Two stars, you do about 40% more business, and with three stars, you'll do about 100% more business."

The concept of “uncertainty in assessment of quality” has led to rankings and awards everywhere (think EGOT = Emmy’s + Grammy’s + Oscar’s + Tony’s). However, as information becomes more widespread and culture fractures, these awards are clearly losing their cachet.

Michelin also faces competition from the likes of the James Beard Award, Zagat and New York Times Review. Separately, young people are relying on social apps for food recommendations (a Google exec recently said ~40% of young people are finding food spots on TikTok or Instagram instead of Google Maps or Search).

One part of the Michelin brand that seems very safe: the 3-star ranking, which only 143 restaurants in the world have attained. There are only a few thousand total seats a year at these locations, creating a scarce luxury-type good that rich folk are willing to spend money on.

How does Michelin Guide make money?

Since launching in 1900, Michelin has sold more than 30 million Guides. That’s an average of ~250k a year but we can safely assume there’s been a lot more purchases in recent year (example: Michelin sold 100k Guides in Japan on the first day it launched in the country in 2007).

Let’s guesstimate that Michelin sells 1m Guides a year at $20 a pop, so $20m a year in sales. What about other revenue streams? The Guide has a digitally property, runs events and licenses the ranking system (eg. to TripAdvisor).

Michelin also started charging countries for coverage. Eater reports that South Korea’s tourism board paid Michelin $1.8m to launch a Seoul Guide and Thailand’s government paid $4.4m over 5 years (~$800k a year) for its own Guide.

These weren’t payments for positive reviews. Just payments to launch a Guide for a country. However, it’s not a huge revenue stream if we consider the majority of restaurants (Europe, America, Japan) aren’t paying comparable fees.

Michelin the tire company doesn’t break out the Guide’s financials. But a 2011 report by Financial Times said the Guide loses $24m a year. If the Guide is still losing that much money, then ~$24m represents ~0.1% of sales and is marginal for such a powerful marketing tool.

What are the expenses? I’m guessing the usual stuff like admin, publishing, web/app and marketing.

But the most fun expense to talk about are the food inspectors.

According to Michelin Guide’s press kit, inspectors are the “main protagonists” in the story. They all have backgrounds in hospitality and are employees of Michelin (to maintain objectivity, Michelin pays for the inspector’s meals vs. the restaurant providing free meals).

The inspector’s job has been described as “the C.I.A. but with better food” and their work schedule is crazy:

A MICHELIN guide inspector eats around 250 anonymous meals a year (known internally as table tests), spends 160 nights in hotels, makes 600 visits, and writes more than 1,000 reports to create a new selection every year

They are anonymous and only reveal themselves to a restaurant if they have additional questions (and only after the meal). Twice a year, inspectors get together to swap notes with the Guide’s editor. They award stars in a “unanimous collegiate manner” (so, basically the opposite of discourse on Twitter).

Here is my really quick and dirty (very dirty) assumption on the expense of Michelin inspectors:

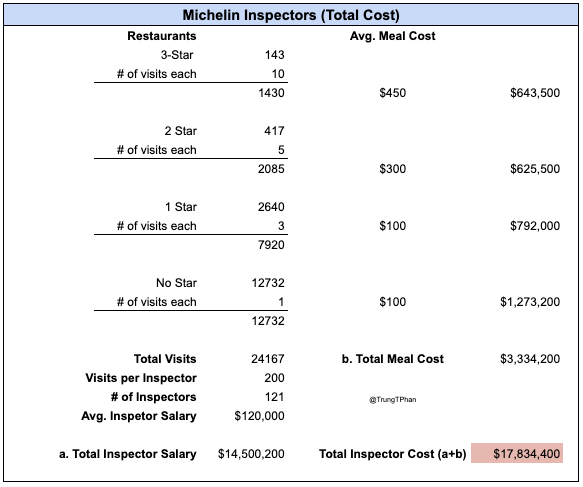

# of total visits: There are 15k+ total restaurants that the Guide covers (not everything gets a star). Michelin visits each starred restaurant multiple times a year with different inspectors: (3 stars = 10x visits) + (2 stars = 5x visits) + (1 star = 3x visits) + (no star = 1 visit) = 24,167 total visits

Cost of visits: Assuming the following all-in costs for 3-star ($450), 2-star ($300), 1-star ($100) and no-star ($100), the total meal costs is $3.3m.

# of inspectors: Assuming each inspector visits 200 restaurants a year, you’d need 121 inspectors. And if each is paid $120,000 ($100,000 base + $20,000 hotels) that’s a total annual salary cost of $14.5m.

Total: Assuming my awful assumptions are even remotely in the ballpark, that’s a total annual inspector expense of $17.8m.

When you consider that the average 30-second Super Bowl ad cost $6.5m this year, $17.8m every year for Michelin inspectors looks like an incredible deal.

Why do some chefs give back the Michelin stars?

Michelin — which combines a rigorous review process with over a century of experience — has clearly established itself as the gold-standard arbiter of quality for restaurants.

Here is the Guide’s official 5-point ranking criteria:

1. Quality of products

2. Mastery of flavour and cooking techniques

3. The personality of the chef represented in the dining experience

4. Harmony of flavours

5. Consistency between inspectors’ visits

And here are the star ratings:

Let’s be honest, though. WTF does “harmony of flavours” or “worth a special journey” mean? It’s all very very subjective (*cough* uncertainty in the assessment of quality *cough*) and opaque.

Starred restaurants never know when they are being judged, so literally every single meal that goes out the door could be a chef’s undoing.

Consistency is a huge deal. If Restaurant X is reputed for the best Banh Mi in the world, then it should serve the best Banh Mi in the world…every single time. It's an extraordinary amount of pressure for a kitchen, which is already a pressure-filled environment.

Not to mention the pressure from customers.

And once you have the stars, the fear of losing them adds to the stress (aka the endowment effect, the phenomenon in which we may irrationally value something based on the fact we own it vs. if we never owned it at all).

Per a widely-read CNN article, a number of Michelin chef’s have walked away from the star-ranking system:

South Korean Eo Yun-gwong sued Michelin to remove stars, saying “Michelin guide is a cruel system. It's the cruelest test in the world. It forces the chefs to work around a year waiting for a test [and] they don't know when it's coming."

Spanish chef Julio Biosca returned the star saying he was tired of making complex multi-course menus.

Belgian chef Frederick Dhooge gave back a star because he wanted to get back to cooking simple dishes like fried chicken, which isn’t considered “star-worthy” (Ed note: fried chicken should 10000% be “star-worthy”)

Gordon Ramsay weeped after losing a star and said “it was like losing a girlfriend”

Tragically, Bernard Loiseau — one of France’s top chefs — killed himself in 2003 and many believe it was partly due to fear that he was about to lose a Michelin star.

The late Anthony Bourdain had strong thoughts on how the Michelin system completely warps incentives and creativity:

“I know many of the three-star Michelins never change their menu in order to have perfect consistency. It’s basically robotic cuisine; they cannot afford to change, because that was the winning formula…. Emotionally, I’m going to want to cook something else than what I’ve done.”

Renee Redzepi was the world’s top chef in the early 2010s and closed his original 3-Michelin star restaurant (Noma) in 2016. Why? Because the success restrained his creativity:

"In hindsight now, I can see no matter what, success pushes you into some sort of formal way of thinking. Even in your own creative space. You become more square.”

Michelin obviously defends its process and rebuts that the chef’s don’t actually own the stars. It’s awarded to the restaurant. So I guess technically, they can’t “give back” the stars (nor can they “take the stars” with them if they leave).

I’m not a chef, but that feels annoying.

A separate comment from Bourdain sums it up well: “[The Michelin star process] is like sausage—no one wants to see how the hell it’s made.”

Finals thoughts

With that context, let me address one last lingering question I’m sure you have: “Trung, was Mugaritz actually any good?”

Here’s my roundabout answer. After our meal, I asked if it was cool to tour the kitchen and meet the team. Mugaritz was kind of enough to oblige and I met the chef, who told me straight up that taste was not the restaurant’s number one priority.

Rather, the main objectives are to craft an experience, create interesting textures, engage the senses and dream up unusual gastronomical eats like a chemist in the lab (Mugaritz has a big research team).

It was def an experience. While I found half the dishes pretty meh, a few were amazing and I still distinctly remember various sensory elements: 1) the loud crunch of a dried apple cracker; 2) the smell of sake smoke that was repeatedly wafted into my face (low cal meal right there; 3) frozen and overly-heated utensils; and 4) 10lb copper bowls that were so heavy the restaurant only lets a server carry 4 at a time (so they don’t injure their backs).

Ultimately, the status signalling is something I will take with me forever: I now refuse to eat with room-temperature cutlery or bowls that can’t double as dumbbells.

For more interesting business and tech content every Saturday, subscribe to the SatPost newsletter below:

Links and Memes

More on my Spain trip: Last week I wrote about Picasso, Gaudi and why Spain is in the wrong time zone.

Twitter vs. Elon: As many of you know, Twitter is suing Elon to force him to close his $44B acquisition offer. Matt Levine has (of course) the best take on the lawsuit. I read the document only to see how many of Elon’s tweets were in it. There are at least 17, including these three…which are hilarious because Twitter’s lawyers are describing shitposts — including a poop emoji — in very formal language:

New podcast alert: The Not Investment Advice Investment (NIA) podcast interviewed Michael Saylor last week. Yes, I realize the irony here: Saylor is one of the biggest Bitcoin proponents in the world and our podcast is called Not Investment Advice (NIA). Some highlights:

What it would take to change his view of Bitcoin

His thoughts on Ethereum and the recent DeFi shenanigans

Which of the Big Tech firms are best-placed to win in crypto

Did people in the past “look” older?: According this amazing YouTube video from VSauce, the answer is two fold:

people today are aging “more slowly” (aka we do look younger due to improved “lifestyle, nutrition, smoking habits and healthcare”)

however, a big part of why people in the past look “older” is we consider certain styles and grooming techniques “older looking” and obviously people from different time periods are rocking different outfits

Example: here is a viral tweet comparing a 34-year old “Norm” (from Cheers) with a 34-year old today.

Sure, Norm looks older. But that’s also because of the get-up. Here’s a version of Norm that would fit in perfectly in 2022:

And here are some memes:

Finally, here was the best tweet about the amazing galaxy photos from the James Webb telescope (which has blown the Hubble telescope out the water):