The Science and History of the iPhone Screen

In 2007, one conversation convinced Steve Jobs to pick Corning and Gorilla Glass for the iPhone.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about the science and history behind the iPhone’s glass screen (manufactured by Corning).

Also this week:

Elon Musk vs. Larry Page (on AI)

The NFL’s $20B business

…and them fire memes (including Chobani yogurt)

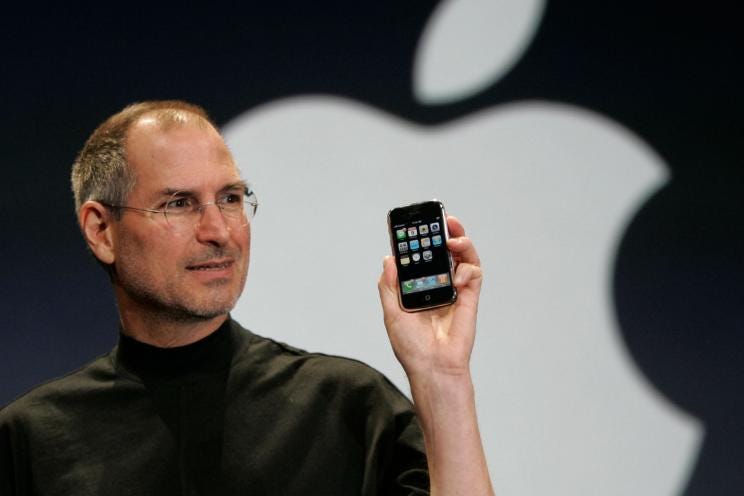

Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone on January 9th, 2007.

So much lore has come out of the keynote presentation but my favourite detail is that the screen on the iPhone that day was made of plastic.

Why does that tickle my fancy? Because when the phone was shipped in June 2007, the screen was made of glass and the story of how that happened is one of the most insightful — and funniest — Jobs story ever.

It is also a great window into the science and history of Corning (the $27B industrial firm that specializes in glass and ceramics).

So, let’s discuss:

iPhone going glass

The science and history of Gorilla Glass

The current state of Corning

iPhone going glass

While the iPhone launch demo was a success, Jobs was very unhappy with the plastic screen (which was similar to the iPod screen). His major gripe was that the keys in his pocket left scratch marks on the device.

The small iPhone team within Apple had previously tested glass and briefly attempted to develop materials in-house. But the screen kept cracking during drop tests.

In his book The One Device, Brian Merchant recounts a conversation Jobs had with a mid-level Apple executive, who you will feel sorry for after reading this exchange:

“Look at this,” [Jobs] said to a midlevel executive, holding up a prototype iPhone with scratch marks all over its plastic display—a victim of sharing his pocket with his keys.

“Look at this. What’s with the screen?” “Well, Steve,” the exec said, “we have a glass prototype, but it fails the one-meter drop test one hundred out of one hundred times—”

Jobs cut him off. “I just want to know if you are going make the fucking thing work.”

Three notes on this conversation:

I can’t confirm but am guessing that no Apple employee ever started a conversation again with the words “Well, Steve”.

Jobs wanted glass and the iPhone team had six months to deliver.

The iPhone Corning Glass story is up there with the time Apple was developing the iPod and Jobs felt a prototype of the MP3 player was too bulky and heavy. Jobs demanded a smaller version and took an unusual step to make his point, per David Brown writing in The Atlantic:

The engineers explained that they had to reinvent inventing to create the iPod, and that it was simply impossible to make it any smaller. Jobs was quiet for a moment.

Finally he stood, walked over to an aquarium, and dropped the iPod in the tank. After it touched bottom, bubbles floated to the top."Those are air bubbles," he snapped. "That means there's space in there. Make it smaller."

Enter Corning Inc, which was founded in 1851 as Corning Glass Works to…err work on glass.

In 2005, the company was monitoring the rise of high-end flip phones (e.g. Razr, Noika) and thought it could commercialize a scratch-resistant glass that was developed decades prior. The material was dubbed Gorilla Glass and filled a need for a consumer glass market that was “either too fragile and shatter-prone or too thick and unsexy”.

Not long after the iPhone demo, Jobs met with Corning’s CEO Wendell Weeks to discuss Gorilla Glass and it was a next-level conversation.

As Merchant explains:

Jobs told Weeks he doubted Gorilla Glass was good enough, and began explaining to the CEO of the nation’s top glass company how glass was made.

“Can you shut up,” Weeks interrupted him, “and let me teach you some science?”

Jobs was sold, and, recovering his Jobsian flair, ordered as much as Corning could make—in a matter of months. “We don’t have the capacity,” Weeks replied. “None of our plants make the glass now.” He protested that it would be impossible to get the order scaled up in time.

“Don’t be afraid,” Jobs replied. “Get your mind around it. You can do it.”

According to [Walter Isaacson’s biography on Jobs], Weeks shook his head in astonishment as he recounted the story. “We did it in under six months,” he said. “We produced a glass that had never been made.”

Do you remember that awesome scene in The Martian, where Matt Damon’s character has to plant his own potatoes because he is stranded on Mars without enough food? And he motivates himself by saying “I'm going to have to science the shit out of this?”

That was an awesome scene and line.

Well, I’m here to tell you that Weeks saying to Jobs “let me teach you some science” is a 1000x better use of the word “science” than Damon’s line and one of the greatest clap-backs in corporate history (on a related note: Gorilla Glass is about 1000x stronger than plastic).

Also, isn’t that the most Jobsian story ever? It hits all the notes of the Jobs mythology:

Total self-assurance (mixed with douchebaggery): “he…began explaining to the CEO of the nation’s top glass company how glass was made”

Visionary: Jobs was willing to change his mind if convinced and — after being taught some science — he saw the potential of Gorilla Glass.

Reality distortion field: “Don’t be afraid…get your mind around it, you can do it.”

That is the full Jobs experience right there.

Science and history of Gorilla Glass

So, what science did Weeks — who is still Corning’s CEO — teach Jobs?

Let’s answer that question by looking at the OG way of strengthening glass. The process is called tempering and dates back hundreds of years. Here is the basic science as told by one of the top search results I found for “tempering glass”:

Manufactured through a process of extreme heating and rapid cooling, tempered glass is much harder than standard glass. […]

The glass is heated in a furnace to over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit and then quickly cooled using high-pressure air blasts. This cools the outer layers of the glass much more quickly than the internal layers, so when the inside cools, it pulls away from the outer layers. As a result, the inside remains in a state of tension, while the outside goes into a state of compression. These competing forces are what make tempered glass so much stronger than [standard] glass.

In the 1950s, Corning’s then president gave the company’s head of research a very literal assignment: “Glass breaks. Why don’t you fix that?” (I cross-checked this statement with multiple sources and can confirm that glass does indeed break)

Corning’s research team delivered two breakthroughs over the next decade.

The first is called the “Fusion Draw” process. You can watch the 90-second video from Corning…

…and/or just enjoy this stylized summary:

Hot stuff in a big container: Corning engineers combine sand — or silicon dioxide — with other glass-making ingredients and heat the mixture to 1000 degrees Celsius.

Overflowing hot stuff: The molten glass lava goes into a suspended trough and flows over the sides.

Glass: The molten glass cools as it overflows, forming super-thin glass sheets in mid-air, which are then cut by machines.

Today, no human hands ever come into contact with the glass, even after it has cooled and is moved around.

An important detail for sand is that it has a very high melting point (~1,700 degrees Celsius), which means that it can be combined with other elements to create new properties before it cools and forms glass. This property leads us to the second major solution — and one specific to Gorilla Glass — that Corning developed to strengthen glass.

The process is called an “ion exchange” and I’ll teach you with some science using bullet points and an image from Lehigh University:

Sand is treated with a chemical to create sodium-heavy aluminosilicate

This chemical-treated glass has a lot of sodium molecules (Na+)

Before it fully cools, the chemical-treated glass is dipped in a potassium salt bath, which has a lot potassium molecules (K+)

Potassium molecules (K+) are heavier than sodium molecules (Na+) and replace those molecules in the glass.

The larger potassium (K+) molecules create more compression and strengthen the glass

“[Corning] called the new glass Chemcor,” according to Merchant’s One Device. “It was much, much stronger than ordinary glass. And you could still see through it.”

Officially launched in the mid-1960s, Chemcor was a breakthrough but Corning could never find a market for the material. Some failed product launches included phone booths, eyeglasses and windshields (the glass was too strong for automakers because if a person’s skull goes flying into it after a car crash, the skull does not remain intact).

The product remained untouched until Weeks taught Jobs some science. Corning took Chemcor off the shelf and collaborated with Apple to make it thin enough to be used as a smartphone screen.

A 2012 Wired article by Bryan Gardiner breaks down Corning’s incredible effort to “get its mind around” the problem and meet Jobs’ June iPhone delivery date:

By the end of March 2007, Corning was closing in on its formula. But the company also needed to manufacture it. Inventing a new manufacturing process was out of the question, as that could take years. To meet Apple's deadline, two of Corning's compositional scientists, Adam Ellison and Matt Dejneka, were tasked with figuring out how to adapt and troubleshoot a process the company was already using. They needed something capable of spitting out massive quantities of thin, pristine glass in a matter of weeks.

There was really only one choice: fusion draw. In this technique, molten glass is poured from a tank into a trough called an isopipe. The glass overflows on each side, then the two streams rejoin under the isopipe. It's drawn down at a prescribed rate by rollers to form a continuous sheet. The faster it's drawn, the thinner the glass.

Corning's one fusion-capable factory in the US is in Harrodsburg, Kentucky. In early 2007, that plant's seven 15-foot-tall tanks were going full blast, each churning out more than 1,000 pounds per hour of sold-out LCD glass for TV panels. One tank could meet Apple's initial request. But first the old Chemcor compositions had to be reformulated. The glass not only needed to be 1.3 mm now, it also had to have better visual characteristics than, say, a pane in a telephone booth. Ellison and his team had six weeks to nail it. To be compatible with the fusion process, the glass also needed to be extra stretchy, like chewing gum, at a fairly low temperature. The problem was, anything you do to increase a glass's gooeyness also tends to make it substantially more difficult to melt. By simultaneously altering seven individual parts of the composition—including changing the levels of several oxides and adding one new secret ingredient—the compositional scientists found they were able to ramp up the viscosity while also producing a finely tuned glass capable of higher compressive stress and faster ion exchange. The tank started in May 2007. By June, it had produced enough Gorilla Glass to cover seven football fields.

The whole Chemcor-to-Gorilla Glass story makes me wonder how many random science breakthroughs currently exist but have been waiting for decades to be commercialized. I’m guessing there is a lot.

The current state of Corning

During the smartphone revolution, some form of Gorilla Glass — which is primarily manufactured in Harrodsburg, Kentucky — has been used in over 6 billion devices. There’s an argument to be made that Gorilla Glass has touched more hands than any other consumer product ever.

With that type of consumer footprint, it’s reasonable to assume that Corning is largely at the whim of Apple’s wants and needs.

It turns out that this is not the case.

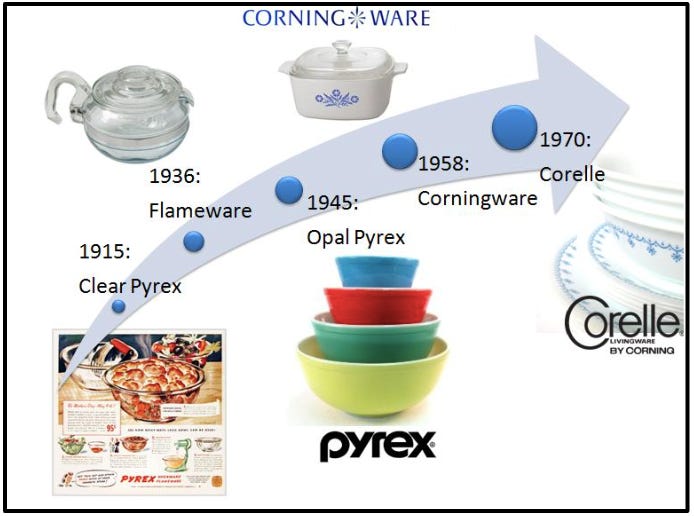

Remember, Corning is over 170 years old and has created glass or ceramic products for many different industries.

If you check your grandparent’s kitchen, you may see some of Corning’s staples from the 20th century: Pyrex, Flameware, Corningware or Corelle (though, Corning did sell its kitchen products division in 1998).

At the time of the iPhone’s launch in 2007, Corning’s largest revenue division was display technologies because thin sheets of glass make really good LCD and OLED screens (TVs, laptops, tablets etc). On a related note, the South Korean electronics giant Samsung owns ~10% of Corning via its Samsung Displays division.

Last year, Corning had ~$14.2B in sales with a new top dog in its revenue mix:

Optical Communications (34% of sales; $4.8B): Corning invented the first low-loss optical fiber in 1970. The explosion in bandwidth use (video, data, voice) over the past decade has been a boon for this business segment (it should be noted that Corning also was hit hard during the telecom bubble bust that coincided with the Dotcom bubble).

Display Technologies (22%; $3.1B): The aforementioned LCD and OLED screens.

Specialty Materials (14%: $2B): Our old friend Gorilla Glass falls under this segment (used mostly in mobile devices and smart watches). But Corning also makes special materials for the semiconductor, aerospace and telecom industries.

Environmental Tech (11%; $1.6B): Mostly solar panels.

Life Sciences Tech (8%; $1.1B): Laboratory equipment (jars, bottles, pipettes, test tubes and other items found on the show Breaking Bad).

The diversity in Corning's business line looks particularly important when you consider what happened to GT Advanced Technologies, a materials company that Apple contracted to make sapphire screens for the iPhone 6. This partnership was struck in the early 2010s, with Apple loaning $578m to GT to build a plant in Arizona for making synthetic sapphire crystals. The partnership collapsed and GT filed for bankruptcy. It alleged that Apple had broken the deal (the SEC later agreed that Apple was allowed to walk away because GT couldn't create enough quality screens).

Corning’s relationship with Apple has obviously been much more fruitful.

Since 2017, the iPhone maker has invested ~$450m from its $5B Advanced Manufacturing Fund into Corning for the research and development of better screens (more broadly, Corning spends ~10% of revenue on R&D to stay relevant).

What does “better” mean for screens? Typically, some level of strength (does screen crack from drops?), scratch resistance (self explanatory) and thickness.

There was a period towards the end of the 2010s during which Gorilla Glass saw very little improvement in terms of scratch-resistance. Meanwhile, the drive to create ever-thinner screens meant that drop-protection was not advancing very quickly (Corning says that if the current generation of iPhone screens were as thick as the first version, the screens would be indestructible).

In 2020, Corning and Apple announced a screen called the Ceramic Shield for the iPhone 12 (and future models). It’s supposed to be more scratch resistant and offer 4x more drop protection than previous iPhones. This is why it’s so pricey to replace a screen if it does crack.

I’ll shut up and take their word on the science. But just to be safe: I also buy multiple screen protectors and a heavy-duty case for any iPhone (and from painful personal experience, just pay for the Apple Care insurance if you’re buying a brand new one).

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email. If you press this blue button below, you can try AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Links and Memes

Elon Musk vs. Larry Page (on AI): Walter Isaacson has a new book on Elon Musk coming out. Time Magazine posted a wild excerpt from it that details Elon’s falling out with Google co-founder Larry Page — they used to be boys — because of AI:

They had known each other for more than a decade, and Musk often stayed at Page’s Palo Alto, Calif., house. The potential dangers of artificial intelligence became a topic that Musk would raise, almost obsessively, during their late-night conversations. Page was dismissive.

At Musk’s 2013 birthday party in Napa Valley, California, they got into a passionate debate. Unless we built in safeguards, Musk argued, artificial-intelligence-systems might replace humans, making our species irrelevant or even extinct. Page pushed back. Why would it matter, he asked, if machines someday surpassed humans in intelligence, even consciousness? It would simply be the next stage of evolution.

Human consciousness, Musk retorted, was a precious flicker of light in the universe, and we should not let it be extinguished. Page considered that sentimental nonsense. If consciousness could be replicated in a machine, why would that not be just as valuable? He accused Musk of being a “specist,” someone who was biased in favor of their own species. “Well, yes, I am pro-human,” Musk responded. “I f-cking like humanity, dude.”

In 2012, Elon invested $5m into the AI startup DeepMind. At the end of 2013, Google made a move to acquire the company. Elon tried to block the deal, telling its founder Demis Hassabis, “The future of AI should not be controlled by Larry.” Google ended up acquiring the startup for ~$500m in 2014, which led Elon to co-found OpenAI the following year (he left that organization in 2018).

The NFL’s business, explained: Joe Pompliano has an overview of the NFL’s monstrous business including these nuggets:

NFL did more annual revenue in 2022 ($19B) than the combined sales for Premier League, La Liga, Bundesliga, Serie A, and Ligue 1.

“NFL games represented 82 of the top 100 most-watched US TV broadcasts in 2022, including 23 of the top 25”

“The average NFL franchise is now worth $5.14 billion, according to Sportico. This is a 24% increase from 2022, and every team is now worth at least $4 billion.”

“Lamar Jackson ($82 million) will be the NFL’s highest-paid player in 2023 after signing his 5-year, $260 million extension this summer.”

***

Here some other baller links:

“Is Bach the greatest achiever of all time?” Economist Tyler Cowen asks the question in a fascinating post. He provides an interesting set of criteria and tosses out some other candidates (Shakespeare, Beethoven, Plato, Aristotle).

Do you use Rotten Tomatoes before watching a movie or TV show? If so, check out this article from Vulture that investigates how people are manipulating the website — which is so influential in Hollywood — by paying off amateur reviewers.

ABBA’s $175m virtual tour: The famed Swedish 70s pop group was digitally cloned to create life-like avatars — or ABBA-tars — for a concert series called ABBA Voyage. Created by Simon Fuller (American Idol producer), it cost $175m to build a special 3000-person concert hall in London for the virtual performances (the real ABBA artists aren’t at the shows).

Since May 2022, the show has made $150m. Tickets cost ~$100 and the show is printing $2m a week (it can keep doing so indefinitely and runs 7 days a week). This model is the future for aging artists but is kind of a depressing when you consider that nostalgia for older music could snuff out new music. Having said that, I effin' love ABBA and want to watch it. You can check out the trailer here.

iPhone 15 Problems: Lastly, the new iPhone 15 will be announced this upcoming week. But all Apple eyes are on China. The Chinese government officials (and employees at some state-owned enterprises) are banned from using iPhones at work over national security concerns. The move is clearly part of the broader China-US trade war and could pose a huge problem for Apple if it expands to the broader Chinese consumer market (~20% of Apple revenue, which is the equivalent of ALOT of Ceramic Shield).

…and here them fire tweets:

Soren Iverson is a designer for Cash App and — since the beginning of the year — has created a viral tweet everyday by creating satirical app features (check this banger below). Anyways, Soren came on our Not Investment Advice (NIA) podcast and explained his baller creative process.

I didn't know Elon had an investment in Deepmind. That's interesting!