The Speed of Information

Putting social media coverage of Israel-Palestine into historical context.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, I want to share some thoughts on the information sphere following the brutal terrorist attack in Israel last week. My thoughts and prayers are with Israel, Jews around the world and millions of innocent Palestinians, with hopes for eventual peace.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, images from the conflict — real and fake — spread widely on social media.

It was the largest land invasion on European soil since World War II and it was surreal to watch a global-changing conflict unfold in real-time.

Not just watching. But also trying to sift through information — and a lot of misinformation — in the full fog of war.

Facebook (now Meta) was founded in 2004. Twitter (now X) was founded in 2006. And TikTok was created in 2016.

These tools for media consumption are a blip in the timescale of humankind.

War and conflict have historically been consumed through top-down controlled mediums (like one newspaper a day) with a very different cadence than “anytime I open my smartphone” (which we do over 100x a day).

As many of you know: last weekend, there was a horrific terrorist attack in southern Israel. Hamas — the terrorist organization that has controlled the Gaza Strip for over a decade — murdered over 1,300 Israelis and kidnapped more than 150 hostages.

More innocent people — including countless Palestinians — will suffer as the conflict expands in the coming weeks.

In an article titled “You're not going to like what comes after Pax Americana”, Noah Smith makes the case that this attack is “a demonstration of America’s decreasing ability to deter conflict throughout the world”. It follows Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and — last month — Azerbaijan invading Nagorno-Karabakh and expelling 120,000 Armenians.

America stepping away from its role as a global policeman combined with the rise of China increases the surface area for more conflict as nations jockey for power.

The likelihood of more conflict means more unfiltered images and videos bombarding us, which takes me to the point of this article: the speed of the current information / misinformation environment is so vastly different than the previous thousands-year history of human conflict.

It’s so much more than even the Egypt Revolution of 2011, which is often brought up as a social media turning point.

The past two years is a complete step change in audience size and and the volume of content.

Take Facebook. Over the past 12 years, it has grown from 845m to over 3B users across all its apps. Then there is TikTok. The Chinese-owned app is the #1 platform for social video sharing and went from 0 to 1B+ users since its founding.

And it is not clear that we are prepared to handle this torrent of media.

Consider the invention of ultra-highly processed foods in the second half of the 20th century. The human body is not evolved for such easy access to calories and — in many parts of the world — it has led to an obesity epidemic.

Now, think about the current media and information environment. There is mounting evidence that social media on smartphones over the past decade — with its dopamine triggers and instant access to the entire gamut of emotion (anger, lust, jealousy, pride, disgust, happiness, sadness) — can lead to various psychological issues, such as increased depression among teenagers.

What about violent images of war and tribal hate speech instantly served up by algorithms designed to hook your attention?

This is not normal on an evolutionary timescale.

Let me frame how atypical this information environment is with six stories from previous conflicts. I’ve shared some of these ideas before and think they are worth considering in light of the past week:

Telegraphs in the Civil War

Posters in World War I

Radio in World War II

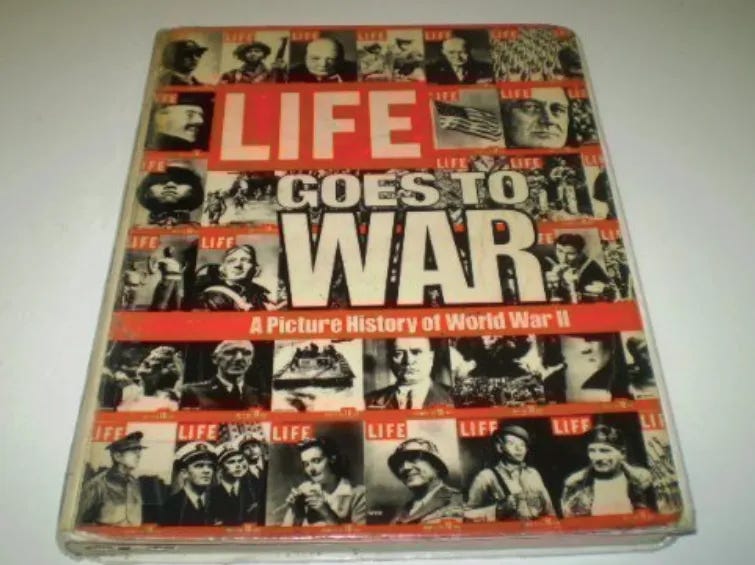

Life Magazine and the images of World War II

Walter Cronkite and the Vietnam War

Air Force One during 9/11

Telegraphs in the Civil War

When the American Civil War began in April 1861, the US Military Telegraph Corps. laid “15,000 miles of telegraph wire across battlefields that transmitted news nearly instantaneously from the front lines”, per History.

All communications from that telegraph network — literally 100% — was sent to the library room of the War Department, which was next to the White House.

Other than the White House, Lincoln spent more time in the telegraph room than any other place during the Civil War:

David Homer Bates, one of the four original members of the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps, recounted in “Lincoln in the Telegraph Room” that several times a day, Lincoln sat down at a telegraph office desk near a window overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue and read through the fresh stack of incoming telegrams, which he called “lightning messages.” As telegraph keys chattered, he peered over the shoulders of the operators who scribbled down the incoming messages converted from Morse Code. He visited the office nearly every night before turning in and slept there on a cot during pivotal battles.

From 1861-1865, the President of the United States was the only person in the country receiving all the flow of information related to the war (the Confederates never built a comparable telegraph network).

Today, literally billions of people are being flooded with images, intel, news, updates and propaganda at every waking second.

Obviously, we are not getting the full picture but it’s an astounding amount of information (and mis/dis-information, too).

Each of us has Lincoln’s telegraph room in our pocket.

Posters in WWI

Last weekend, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei sent an X post in support of Hamas, following the brutal terrorist attack. The official Israel government account replied "It's easy to be brave when you're hiding behind a keyboard. You and your Hamas friends will regret your barbaric actions very soon."

These posts could be written in minutes and instantly hit hundreds of millions of eyeballs.

Contrast that to World War I, which the LA Times notes is the first time “in which mass communication techniques were controlled and deployed by governments for a wide variety of patriotic aims: to demonize their enemies, to attract soldiers, to bolster the morale of their citizens, and to fund the staggering costs of full militarization.”

All of the tools available — radio, film, newspapers — were used to sway international opinion, but the most salient remnant of the period is the propaganda poster.

Think about how long it took to: 1) mock up the posters; 2) mass print; 3) place them all across the country (or airdropped into enemy territory).

Posts on X or short videos on TikTok accomplish the same goal — and are in the hands of millions of users — in a tiny fraction of the time.

Radio in WWII

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) was famed for his “fireside chats”, which were evening radio addresses to millions of American citizens.

When discussing his leadership during WWII, these “fireside chats” are often brought up as a key example. During his record four-term presidency (1933-1944; he died before completing the last term), FDR only actually gave 30 of these speeches.

The first of them were meant to quell concern over The Great Depression, while later ones were about fighting Japanese and German fascism.

Add it all up and we’re talking 2-3 addresses a year.

Again, contrast that with the instantaneous media from leaders on all sides of the conflict — available every second of every day — which are reaching even more people than FDR’s speeches.

Life Magazine and the images of WWII

Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History is the greatest podcast ever made. Period.

His most recent series is a 6-part (20hr+) story of Imperial Japan during the Second World War.

It is spectacular.

In the series, Carlin talks about how images from WWII — which took place between 1939-1945 — were not widely seen by Americans until the 1970s, when Life Magazine released a collection of all its work during the Second World War (“Life Goes to War”).

Life Magazine — which was the #1 photo publication in the 1940s — did release weekly issues during the war but few Americans had the opportunity to see everything in one place. The photos were also very curated (in early Life Magazine coverage, it was forbidden to show photos of dead soldiers).

Think about that: imagery from the most devastating war in human history wasn’t widely seen or known in America until three decades after the end of the conflict.

Images and videos coming of out of the Middle East (and Ukraine over the past 18 months) are flooding our smartphones from news organizations, citizen journalists, trolls and bots.

Social media feeds have commoditized content. So, we are being fed these horrific visuals as we scroll through memes, basketball highlights and trailers for a random streaming re-boots.

How are our brains supposed to handle the second-by-second swing in emotions?

It is such a new phenomenon on the timescale of our history.

Walter Cronkite and the Vietnam War

The past decade has seen the decay of key gate-keeping and sense-making institutions (Hollywood, major TV networks, newspapers, academia). There are now so many voices — using internet-native mediums (YouTube, social, podcasts) — vying for influence in the growing void.

Contrast this to how a single person — Walter Cronkite — was able to sway America’s opinion on the Vietnam War.

Background: There is no comparable figure to Walter Cronkite today. He was the anchor for CBS Evening News when the country only had three TV major networks (ABC, NBC, CBS). On average, 29m people tuned into his nightly show.

In comparison, Joe Rogan — the biggest media personality in our fractured media landscape — gets 11m viewers a show.

Cronkite also had the ear of the country’s top businessmen, politicians and media elite. Vietnam was the first truly televised war and his multi-decade long record of objective reporting earned him everyone’s trust.

Trip to Vietnam: As America increased its military presence in Vietnam through the 1960s, Cronkite reported the build-up based on government intel. In February 1968, Cronkite flew to Vietnam to see the situation for himself. He landed shortly after the Viet Cong’s surprise “Tet Offensive” attack.

By the end of the month, he filed this famous report per The Washington Post:

[Cronkite] flew home, and on Feb. 27, at 10 p.m. Eastern time, CBS News aired “Report from Vietnam: Who, What, When, Where, Why?”

The program opens with Cronkite, in a short-sleeve safari shirt, standing in harsh daylight in front of Saigon ruins. It looks like a home movie. Cronkite doesn’t talk about military casualties. There are no images of body bags. One would not know that 416 Americans were killed in Vietnam in the week ending Feb. 3 and another 543 in the week ending Feb. 17 — each a record to that point.

Instead, Cronkite and his producers assess the progress of the war on the terms set by U.S. commanders, such as whether the “pacification” program had suffered a setback from the Viet Cong.

“Who won and who lost in the great Tet Offensive against the cities? I’m not sure,” he says early in the report. “The Viet Cong did not win by a knockout, but neither did we. The referees of history may make it a draw.”

At the close of the hour, Cronkite, back at his desk in New York, delivers his verdict. He acknowledges that what he is about to say is “subjective.” It’s his opinion.

“[I]t seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate . . . [I]t is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.”

“This is Walter Cronkite. Good night.”

After watching the broadcast, US President Lyndon B. Johnson said, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.” A month later, Johnson announced he would not run for re-election.

To be sure, it’s inaccurate to attribute all of America’s anti-Vietnam War sentiment to Cronkite’s broadcast (such sentiment was already on the rise in the lead-up to his report).

There is just nothing in today’s media landscape approximating Cronkite.

Air Force One during 9/11

The most recent example I have of how the current information sphere compares to previous eras is from Apple TV’s 2021 documentary on 9/11.

President George W. Bush was in Florida when the two planes hit the World Trade Centre. For the next 8 hours, the President’s plane — Air Force One — was the only non-fighter jet flying over the United States.

Onboard, he had phone communication. But visuals (via TV) were very spotty. He didn’t receive a full download of information — and see all the horrific damage — until landing back in DC.

Again, contrast that with the instant video access that billions of people have right now.

Of course, we have agency. We can choose to periodically unplug and decide on our information sources.

But there's no going back to pre-social and pre-smartphone and pre-everyone has access to everything instantly.

We are in a completely different information environment. We aren’t just watching these conflicts in real-time, we are learning to psychologically adapt in real-time.

Links

Here are some things I read this week:

Kelvin Kiptum's World Record Marathon [Time of 2:00:35] Reignites Technological Doping Debate (Huddle Up)

Kim Kardashian turned Skims into a $4 billion company. She wants to build the next generation of unicorns with SKKY Partners, her new private equity firm (Fortune)

Could Apple build its own Search Engine? (Bloomberg)

How will weight loss drug Ozempic affect the economy? (Scott Galloway)

The Humanities Degrees — English, History, Philosophy etc. — are in Major Decline….and I wish I had seen this graphic before majoring in History (Chartr)

…and some tweets/X posts:

Last week, I did a deep dive on the 249-year sandal brand Birkenstock. It went public on Wednesday and currently sports a $7B market cap (it IPO’d closer to $9B). CEO Oliver Reichert went on CNBC and dropped some gem lines including: 1) he doesn’t mind if you wear socks with Birkenstock; 2) he said the TAM for Birkenstock was everyone; 3) “Birkenstock didn’t have a Barbie moment, Barbie had a Birkenstock moment”; and 4) this:

Great article! It's important to highlight this speedness over the years which is strictly correlated with the lack of concentration plague that causes people to want more and more in a fast term. Dopamine.