Trader Joe's: The Anti-Grocer

The retailer created a cult brand with sales of $16B+ a year by doing the opposite of industry best-practices (from wages to product to ads).

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about the cult grocery chain Trader Joe’s.

Also this week:

Why Barstool Sports sold for $1

And them fire tweets (including $170k UPS drivers)

PS. If you deal with meeting, video or podcast transcripts, we just added powerful speech-to-text tools in the Bearly AI research app to help you save hours of work.

Before moving back to Canada in 2019, I spent four years working in Boston.

From a shopping perspective, the thing I miss most about living in the United States is going to Trader Joe’s.

I have so many glorious memories of the cult grocery chain: compact stores, great locations, Hawaiian shirts, punny product names, informative newsletters, wine galore and the most baller mix of private label frozen Indian foods (Garlic Naan, Palak Paneer, Butter Chicken).

All of this can be traced back to a series of retailing decisions that Trader Joe’s founder Joe Coulombe made in the mid-1960s.

As explained in his memoir Becoming Trader Joe, Coulombe said that his most important decision was to pay his employees well. That choice influenced future strategic decisions for Trader Joe’s (product, consumer relationships, ads, stores) that were often the complete opposite of industry “best practices”.

To understand the success of the Trader Joe’s model, we will look at:

The retail grocery landscape

The beginning and one big decision

The anti-grocer (product, customers, ads, stores)

The retail grocery landscape

Trader Joe’s was acquired by German grocery giant Aldi in 1979 and — as a private company with a lot of operating autonomy — its financials aren’t readily available (my credit card bills tell me I’ve spent $267,870 on their Garlic Naan, though).

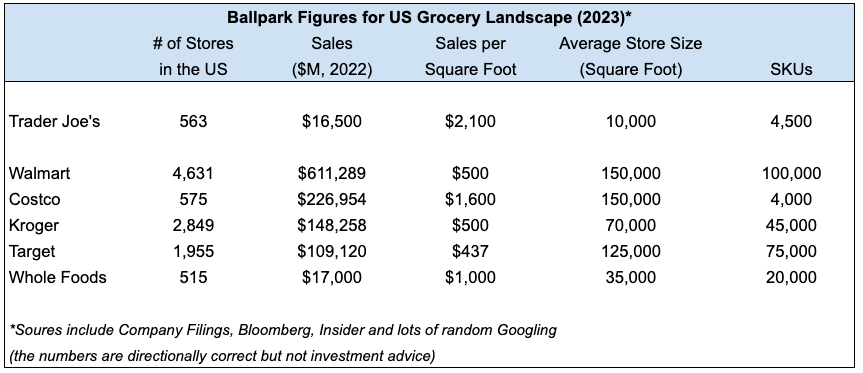

Using public filings and a lot of Googling, here is how Trader Joe’s fits into the US grocery store landscape.

Niche grocer: Trader Joe’s has 563 stores in the US and its annual sales are $16.5B. These figures make it small compared to the major retail grocery chains. Walmart is the whale with 4,631 stores and sales of $611B in 2022. Kroger and Target both have more than 1,900 stores and sales over $100B. Whole Foods is the closet grocery comp in terms of footprint (515 stores) and sales ($17B).

Small stores with fewer SKUs: Trader Joe’s also has a much smaller store size (average size of 10,000 sqft) compared to Walmart (150,000 sqft), Kroger (70,000 sqft) and Target (125,000 sqft). As a result of the smaller store size, Trader Joe’s has a fraction of the products — or stock keeping units (SKUs). Trader Joe’s has less than 4,500 SKUs while the big boys (Walmart, Kroger, Target) have at least 10x that figure.

Exceptional sales per square foot: Trader Joe’s has fewer SKUs but each is specifically chosen to sell well. Located in prime and densely populated areas, the company has a sales per square foot of over $2,100 (which is 2x more than Whole Foods and 4x more than Walmart, Kroger or Target).

I didn’t mention Costco in the above comparisons because it is also an atypical grocer. While Costco’s store sizes are comparable to Walmart or Kroger, it has a similar SKU count to Trader Joe’s but sells in bulkier quantities (hello, comically large tubs of mayo). Costco’s most notable differentiation is that it makes most of its operating profit from the sale of memberships rather than product markups.

Either way, Trader Joe’s has the most impressive sales per square foot figure among grocers (the retailer with the top sales per square foot is Apple at over $5,000).

Let’s dig into Trader Joe’s history to understand how this happened.

The beginning and one big decision

Joe Coulombe was born in San Diego in 1930 and grew up in California.

He was educated at Stanford, where he received a BA and MBA. In the mid-1950s, Coulombe began his retail career by working with the drugstore Rexall. In 1958, the company asked him to launch a chain of convenience stores called Pronto Markets, taking advantage of the fact that 7-Eleven had not yet entered the California market.

After four years — and growth to 6 locations — Rexall decided to leave the convenience store business and Coulombe bought them out for $25,000. However, he had to raise the funds by mortgaging his house, borrowing from his family and asking employees to invest in half of the equity.

Coulombe was betting on himself. As were the employees who bought equity in the business. To do right by them, Coulombe established the “core value” for Pronto Markets: pay people well, which at the time meant a full-time employee made the median family income for California (today, the hourly wage can hit $24 — which is more than double minimum wage — while store managers make over $100k a year).

“This is the most important single business decision I ever made,” Coulombe writes about the high-wage policy (he died in 2020).

There are a few parts to the “pay well” decision:

“Turnover is the most expensive form of labor expense” according to Coulombe. Retail workers often churn, which requires the grocery store to re-train and vet new employees. These factors are a huge drag on productivity. Furthermore, a trusting relationship with workers reduces the ever-present risk of theft.

More cost-savings to be made on product. Coulombe says there is “at least 5x more opportunity to save money in [managing Cost of Goods Sold]” as opposed to labor expenses in grocery retailing. Instead of squeezing your employees — and creating a hostile work environment — he believes that grocers should focus on finding the right suppliers and obtaining the best products at the lowest prices.

By 1966, Pronto Markets had grown to 16 locations but Coulombe’s model would soon be put to a major test with the arrival of 7-Eleven.

“The convenience store business is 90% real estate and 10% all other (merchandising, personnel, etc.),” writes Coulombe. “In real estate, it’s the tenant’s balance sheet that counts.”

And 7-Eleven had a much larger balance sheet than Pronto Markets. When you also consider 7-Eleven’s lower labor costs, the national chain was able to spend more on rent to secure the best store locations.

Coulombe had a few options: he could cut employee wages to spend more on real estate; or he could capitulate to 7-Eleven.

He chose a third path.

“What I needed was a good but small opportunity for my good but small company: a non-commodity, differentiated kind of retailing,” Coulombe says of his decision to stay the course. “Yes, I could have sold out to 7-Eleven and gone to work for them, or somebody else. But the Byzantine management atmosphere [at Rexall]…had convinced me that the only real security lies in having your own business.”

In order to maintain high wages, Coulombe had to be strategic about what he sold. To do this, he had to define his target market.

The solution became apparent after he read two articles.

Rising education levels: A Scientific America article about the explosion in college-educated workers: “The news item said that, of all the people in the United States who were qualified to go to college in 1932, in the pit of the Depression, only 2% actually did. By contrast, in 1964, of all the people qualified to go to college, 60% in fact actually did. The big change, of course, was the GI Bill of Rights that went into effect in 1945.”

A travel boom: A Wall Street Journal article about how the Boeing 747 would go into service in 1970 and greatly reduce the cost of international travel.

These two developments meant that the 1970s would see a growing population of newly-educated shoppers who were curious about products from around the world.

Coulombe dubbed this group the “overeducated and underpaid” and focused on building a “non-commodity, differentiated kind of retailing” to serve them.

In 1967, Pronto Markets was renamed to Trader Joe’s — with the word “trader” meant to evoke travel — and began the transition from a convenience store to a grocery brand that turned traditional retailing on its head.

The anti-grocer (product, customers, stores)

Trader Joe's entered a grocery industry defined by automobiles, brands, and mass media.

The earliest supermarket chains began appearing in the 1930s, coinciding with the rise of network radio. Supermarket shelves were stocked with products from manufacturers that could afford to build brands through radio advertising (e.g., Folgers Coffee, Minute Maid Orange Juice). This branding power became even more significant in the 1950s when TV took over.

It was a symbiotic relationship and all about scale.

Supermarket chains purchased large real estate with parking lots to accommodate cars and shoppers. The national food brands provided the products and spent huge money on ads to generate demand and foot traffic for the supermarkets.

Trader Joe’s adopted a very different model across key dimensions:

Product selection

Customer relationship

Stores

Let’s walk through each point.

***

Product selection

The cult of Trader Joe’s is built around its mix of delicious products that can’t be found anywhere else with great prices.

This approach was a direct response to the tie-up between supermarkets and national food brands.

“[Supermarkets] were shaped by network radio from their beginning,” writes Coulombe. “As a result, supermarket merchandising has always been brand-oriented. One result of this has been that supermarkets have rarely been known for their product knowledge.”

For Coulombe, having “product knowledge” was the key to winning and there was a few ways Trader Joe’s leveraged that advantage.

Early on, Trader Joe’s chose a product mix that could generate enough sales to cover the rents in prime locations (while still providing high wages) by focusing on four criteria:

…I looked for other categories that met the Four Tests: high value per cubic inch, high rate of consumption; easily handled; and something in which we could be outstanding in terms of price or assortment. For example, diamonds met the first test but flunked the second. Fruits and vegetables met the first and second tests but flunked the third because produce requires constant reworking. Fresh meat flunked the third test even more.

The application of the Four Tests had many downstream effects.

Lots of alcohol: Coulombe secured liquor licenses from the Pronto Market days due to its high value per cubic inch (the highest value per cubic inch was cigarettes but Trader Joe’s discontinued them because of theft risk and health considerations). Trader Joe’s became so good at managing alcohol that it famously created the “Two Buck Chuck” ($2 wine) and sells it profitably.

No bulky items: Paper towels and sugar take up space and have low value per cubic inch.

No loss leaders: Every Trader Joe’s product has to be its own profit centre. But each has to do so while offering customers a good price or uniqueness.

Be OK not to carry certain items: Trader Joe’s will cut anything that doesn’t meet the above criteria or falls out of fashion. There is also no pressure to offer “everything”, like a traditional supermarket does.

Anyone who has been to Trader Joe’s knows that they now sell meat and fruit, but it was only after the right vendors were found to help meet the criteria.

Now, you probably have two questions: 1) Does frozen Garlic Naan fit the Four Tests?: and 2) Don’t all grocers want high value per square foot?

The answer to the first question is “obviously, yes”. However, the answer to the second question is nuanced. All things being equal, a higher value per square foot is preferred but the large supermarket chains have other considerations. A big one is that they want to carry necessities — such as sugar and paper towels — so that customers can do a full shop in one place. Also, the supermarket chains have relationships with national food brands that require them to carry certain items (even if they aren’t the highest value options).

With this context in mind, it makes sense that Trader Joe’s carries about 1/10th the SKUs of the largest supermarket grocery chains.

In addition to the Four Tests, Trader Joe’s was able to find differentiated products by taking advantage of regulatory loopholes and becoming great at the process of “intensive buying”.

On the regulatory side, Coulombe writes in the book that “the retailer who masters the skills of dealing with the regulatory authorities erects a threshold that his competitors will have to cross.”

While mass supermarket grocery chains were happy to stock their shelves with anything the national food brands sent them, Coulombe and his team found opportunities by closely reading trade rules and food regulations:

Wine: In California during the 1970s, no single wholesaler had a monopoly on famous French wines. So, the price for the same bottle of wine varied greatly between retailers. Coulombe partnered with one wholesaler and guaranteed a margin, but did so while offering the lowest retail prices. This allowed Trader Joe’s to become one of the state’s biggest wine sellers and it remains so today.

Cheese: America has strict cheese importing laws because of Wisconsin lobbyists. However, the state didn’t produce Brie cheese, so Trader Joe’s took over that category.

Tuna: Coloumbe explains how the grocer was able to get around an import quota on tuna (“By this time we were beginning to realize that Trader Joe’s was becoming a powerful brand. We took the pilchard, relabeled it, and blew it out at a price two-thirds that of green-labeled tuna and half the price of albacore. I became intrigued by this and located the source of the pilchard: a packer in Peru. In June 1982, my wife, Alice, and I went to Lima to visit the canning plant. We witnessed something very interesting: the United States had a quota for imported tuna. Once Peru’s quota had been filled, a biological miracle occurred right there on the canning line. What had been tuna was now pilchard, a member of the herring family, on which there was no quota. The like hasn’t been seen since the Sea of Galilee! To this day, Trader Joe’s is virtually the only retailer of pilchard.”)

After California changed food laws that reduced the profitability of alcohol and dairy in the mid-1970s, Coulombe leaned into “intensive buying”.

This is the process of empowering buyers within the company to become experts in a product category. The buyers established relationships with vendors and negotiated great prices by guaranteeing volume and cutting out the middlemen on generic and unique items (Costco does the same with its Kirkland Signature brand).

Many new products from various cultures were given a “Trader” brand including Trader José’s (Mexican), Trader Joe-San (Japanese), Trader Giotto (Italian), Trader Ming’s (Chinese Food) and more. This practice was phased out in recent years as some shoppers accused the retailer of cultural appropriation and nearly everything is now branded as Trader Joe’s. (UPDATE April 2024: A number of product creators have alleged that Trader Joe’s solicits samples only to later copy and launch a version of a creator’s product).

The company’s “product knowledge” and creation of private-label brands became the most important way to differentiate itself and appeal to the “overeducated and underpaid”. Today, over 80% of its SKUs are Trader Joe’s exclusives. Many of these products have reached cult-like status and are often sold on secondary markets for multiples of the original price

***

Customer relationship

Consider the traditional relationship between supermarkets and national food brands. Who owns the customer relationship? The national food brand, which creates affinity through massive media ad spending.

The supermarket chains were purely for distribution (Coulombe writes that these retailers “became eunuchs—albeit wealthy eunuchs—distributing the brands.”)

By emphasizing product knowledge, Coulombe made it so that shoppers trusted Trader Joe’s to pick the best item in each product category for them.

Here are notable aspects of Trader Joe’s special relationship with the “overeducated and underpaid”:

No promotional sales: Unlike the supermarket grocery chains that frequently ran promos to get people in the door, Coulombe says that “one of the fundamental tenets of Trader Joe’s is that its retail prices don’t change unless its costs change… there are no weekend ad prices, no in-and-out pricing.” Part of having the shoppers trust Trader Joe’s buyers it that they also trust them to get the best price (conversely, frequent promotional sales train shoppers to “wait” for lowers prices).

Educating the customer: Another reason that Trader Joe’s keeps a single price is that it publishes a very popular newsletter called the Fearless Flyer. Coulombe created the document — originally dubbed The Insider Report — as a way to educate shoppers on Trader Joe’s wine selection. The newsletter soon documented all the private label products from around the world. The Fearless Flyer is modelled on teachings from ad legend David Ogilvy, who assumed shoppers were educated and wanted to learn. These explainers — which grew to radio and podcasts — also hammered home the differentiated products.

Inside jokes: Trader Joe’s targets the “overeducated” with ridiculous pun-filled names like Habeas Crispus potato chips, the Sir Isaac Newtons and — Coulombe’s favourite — Heisenberg’s Uncertain Blend of coffee beans (named because it was bag of various coffee beans that fell off a manufactures conveyor belt).

This trusting customer relationship has a great benefit for both parties.

Trader Joe’s doesn’t have to stock many options (eg. it only has one Alfredo sauce, but one that it knows customers will love) and can keep SKUs low. Meanwhile, the shopper doesn’t have to waste time choosing between two or more items.

This latter point helps to sell more product.

In consumer psychology, there is a concept known as the paradox of choice. While "choice" sounds great, too many options can lead shoppers to analysis paralysis (the inability to make a decision or fear of making the wrong choice).

Thus, fewer choices can lead to higher sales (Costco — which greatly influenced Coulombe — also benefits from this dynamic).

***

Stores

Quick reminder: the average Trader Joe’s store is ~10,000 square feet, a minnow compared to Walmart (150,000 sqft), Costco (150,000 sqft) or Kroger (70,000 sqft).

The Trader Joe’s size is a legacy of Pronto Markets convenience store design and Coulombe’s insistence on keeping prime locations to justify high wages. In his book, Coulombe says he liked finding real estate near college students and seniors (discretionary spenders) while avoiding areas populated by new families (who needed all the shopping necessities and big parking lots).

Here are in-store designs that differ from traditional supermarket chains:

Friendly atmosphere: Trader Joe’s employees are upbeat (“pay people well”) and freely interact with shoppers. They playful attitude is enshrined by the office “dress code” of bright Hawaiian shirts. Signage in each store is hand-written and custom to the region (eg. in Boston, I saw drawings of Fenway Park).

Few fixtures: The store interiors are very utilitarian. Fewer SKUs means fewer shelves. Products are displayed in the same cartons that they are shipped in from manufacturers (which reduces the unpacking workload).

Product shipment sizes: “One of the most important decisions we made back in 1977 was to ship to the stores only in whole-case quantities,” Coulombe writes. Whole-case quantities are easier to transport than single-item shipments (which happens for stores with a lot of SKUs). However, the shipments have to weigh less than 40lbs as a precaution against back injuries.

In 2023, Trader Joe's most "anti-grocer" stance is that it does not offer online delivery, curbside pick-up, or partner with third-party delivery apps.

Why? According to Trader Joe's FAQ, "After considering the options, we're still just big ‘ole fans of the neighborhood grocery store where we can say hello when you're looking around wondering - ‘what's for dinner?’”

Final Thoughts (other than “I’m really hungry”)

I’ve been crushing on the Trader Joe’s model but it obviously has drawbacks. You can’t do a full grocery shop there. It is not the most family friendly. The business is still niche relative to the entire grocery market. And the lack of online options feels odd (this stressed the model during COVID lockdowns and led to unionization efforts at some locations).

Still, there are so many valuable takeaways:

Build the right foundation: Coulombe made one crucial decision early — pay people well — and all of the future strategic choices (product, ads, stores) followed from that. A notable comparison is Costco: since it makes most of its money on memberships, its strategic decisions revolve around selling products to customers at the thinnest margins possible.

Counterposition like a G: Coulombe studied the grocery retail landscape and realized that “product knowledge” was a huge competitive advantage. Trader Joe’s offers a unique and differentiated mix of products compared to supermarket chains that are wedded to national food brands.

Hyper-focus on target market: “Trader Joe’s became a cult of the overeducated and underpaid,” writes Coulombe. “Partly because we deliberately tried to make it a cult once we got a handle on what we were actually doing, and partly because we kept the implicit promises with our clientele.”

Disclaimer: I am a part-time member of this cult and look forward to a future reunion with that sweet sweet Garlic Naan.

If you enjoyed that breakdown, subscribe to SatPost for other business and tech deep dives.

Links and Memes

Penn Gaming sold Barstool Sports for $1? Over three years ago, Penn Gaming initiated a ~$550m acquisition of Barstool Sports. It seemed like the perfect fit: Barstool had a massive audience of sports fans that could be funnelled to Penn’s casinos and sports betting app during a legalized sports gambling gold rush.

However, it was a difficult match because Barstool founder Dave Portnoy got into various controversies (documented in numerous hit pieces on him), which hindered Penn’s dealings with gaming regulators. Last week, a wild sequence of events occurred that resulted in Portnoy buying back 100% of Barstool Sports for $1:

Penn has partnered with ESPN to rebrand its Barstool sports betting app as ESPNBet. In exchange for the right to use ESPN’s powerful brand and marketing muscle, Penn is paying the network $1.5B over 10 years and granting $500m worth of Penn stock warrants (Penn says the ESPN deal will drive $1B a year in EBITDA)

ESPN probably told Penn it had to drop Barstool Sports (ESPN and Barstool have a bad history including a failed show that lasted only one week)

Barstool had leverage over Penn. As the ESPN deal was so attractive, Portnoy was able to negotiate to buy back his media brand for “pennies on the dollar”

The deal: Portnoy paid $1 and gave up 50% of any future sale (he says he will never sell again). Also, Barstool has non-compete restrictions on launching a betting app and taking on gambling advertisers. While these latter conditions cap Barstool’s business upside, Portnoy gets total control of his company after netting over $100m on the previous sale. It’s one hell of deal for him.

PS. A shoutout to my Workweek colleague Adam Ryan for details on this deal (definitely check out his newsletter Perpetual for similar deep dives on the media business).

***

And here some other baller links:

Pixar’s incredible technology: Rex Woodbury has a great piece on all the visual/3D modelling technology created by Pixar that has become industry standard. Many lessons for the future of AR/VR/AI.

AI book scams: “Famous Author Jane Friedman Finds AI Fakes Being Sold Under Her Name on Amazon” via The Daily Beast.

MrBeast is the world’s biggest YouTuber. His most popular videos follow the “Jenga storytelling technique”. In Jenga, everyone knows how the game will end — with the tower falling — but there is still so much drama. On a related note, his latest video has him and his buddies stuck on a wooden platform for 7 day. There are 10,008 minutes in a week and it was edited down to 18 incredibly-entertaining minutes.

Barbie crossed $1B at the box office with the help of amazing viral memes. Lulu Cheng Meservey picks the best ones and what we can learn from them.

Singer Sinead O’Connor died at 56. Her cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” is one of the greatest covers ever and this podcast on the song — and her career — is fascinating.

…and here them fire tweets:

This is the best use of the music discovery Shazam app I’ve ever seen:

And, finally, UPS drivers in the US can make up to $170,000 a year with benefits following a union deal. I have only two things to add to the news story: 1) apparently, UPS drivers aren’t allowed to turn left because it’s dangerous and the trucks waste gas while idling in the turning lane (UPS has special map-routing technology to make sure they don’t turn left): and 2) the memes around UPS drivers making $170,000 a year are incredible…and I collected 10 of them here for you in this X thread.

A few years ago, for Salesforce, I did a paper on "employee experience" - how employees rate their jobs and employers. To measure it, I scraped ratings from Glassdoor. Trader Joe's had the highest rating of any grocery retailer.

Then I contrasted the Glassdoor ratings with customer experience - how customers rate shopping there. Ended up with a 2x2 scatterplot where the upper right quadrant is companies loved by their customers and loved by their employees. You can see the scatterplot here:

https://ddarmstrong.github.io/DS1.html

One thing it shows is that there's a strong correlation between employee love and customer love. When employees are happy, customers are too.

The next step was seeing if customer and employee experience had any relationship to revenue growth. Surprise surprise. Companies that fell in the upper right quadrant were growing like crazy. Cue Trader Joe's. (As Mr Phan notes, it's a private company, so it's really hard to get revenue numbers, but I did the best I could.)

I love this article, which added context to everything I've learned about Trader Joe's, where the employees are insanely nice and the customers are practically dancing in the aisles. I love the place too, and I understand why you miss it.

Reminds me of Aldi actually. For a long time they provided only white labelled good quality products at a fair price. And they only have one kind of each product, you just take the waffles they have and you know they’ll be pretty good.

In recent years they added brands like Coca Cola. I guess it’s so people can have a one stop shop where before, they needed to go to another supermarket for their Coke addiction.