11 types of cross-industry innovation

PLUS: AI spam, Disney vs. BuzzFeed.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we’re talking about the book How Innovation Works. And breakdown a list of 11 cross-industry innovations (when one industry borrows an idea from another industry).

Also this week:

AI spam vs. Amazon

When Disney tried to buy BuzzFeed

…and them fire memes (including Bed Bath & Beyond)

How does innovation work?

Well, I’m the wrong person to ask: the most innovative thing I’ve ever done is ask McDonald’s to put Big Mac sauce on my McChicken burger.

The right person to ask is Matt Ridley — a British science writer and former UK House of Lords member — who wrote the book How Innovation Works: Serendipity, Energy and the Saving of Time. It is full of historical examples and provides actual practical analysis on innovation.

Here are my four key takeaways:

1. Inventing vs. Innovating: The book opens with the story of Thomas Newcomen and the creation of the steam engine that bears his name: the Newcomen fire engine. Invented near London in 1712, Newcomen’s engine was the first true breakthrough for turning heat (in this case steam) into mechanical work (the engine pumped water out of mines).

Newcomen’s name is most associated with the innovation, but he built upon existing knowledge and with the help of many other people. While there is a romanticism around heroic individual inventors bending history to create something new, the process of innovation is rarely that clearcut.

As Ridley explains: inventors come up with new products or ideas but innovators transform the inventions into everyday use.

"There is confusion…about whose contribution among several candidates mattered most,” Ridley writes about the Newcomen Engine. “[The engine] was a gradual, stumbling change, with no eureka moment. These features are typical of innovation.”

This is an inspiring insight because it takes the concept of innovation from “only a single genius sitting in a room can crack this problem” to “ideas are already everywhere waiting to be tinkered with to create a breakthrough”.

2. Innovations are inevitable

A related insight is that the process of innovation often looks inevitable in hindsight, as Ridley explains:

Many ideas for technology just seem to be ripe, and ready to fall from the tree. The most astonishing case is the electric light bulb, the invention of which was independently achieved by twenty-one people…Likewise, there were scores of different search engines coming to the market in the 1990s. It was impossible for search engines not to be invented in the 1990s, and impossible for light bulbs not to be invented in the 1870s.

[…] People seem to stumble on the same idea at the same time. Kevin Kelly explores this phenomenon in his book “What Technology Wants”, finding that six different people invented or discovered the thermometer, five the electric telegraph, four decimal fractions, three the hypodermic needle, two natural selection.

In 1922 William Ogburn and Dorothy Thomas at Columbia University produced a list of 148 cases of near-simultaneous invention by more than one person, including photography, the telescope and typewriters…Going further back still, it is striking that the boomerang, the blowpipe and the pyramid were all invented independently on different continents – as was agriculture.

[…] without Charles Darwin, Alfred Wallace did get natural selection in the 1850s; without Albert Einstein, Hendrik Lorenz would have got relativity within a few years; without Leo Szilard, the chain reaction and the fission bomb would have been invented in the twentieth century at some point; without Watson and Crick, Maurice Wilkins and Ray Gosling would have got the structure of DNA within months – William Astbury and Elwyn Beighton already had got the key evidence a year earlier but did not realize it.

The French playwright Victor Hugo once wrote, “No force on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come.” This is often the case with technological innovation, providing an opportunity for those who are actively looking for it.

To be sure, I'm not saying innovation is easy (remember, I'm Big Mac sauce guy). It takes a ton of hard work to create an innovation but the ideas to catalyze them are all around us. As Thomas Edison said — and LinkedIn folk love to put in their About section —“Genius is one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration".

3. Innovation happens “when ideas having sex”

If you are a visual learner, this insight is for you. Ridley makes an apt comparison between innovation and how genes are passed between generations:

[An embryo] when it comes to make sperm and egg cells, swaps bits of the father’s genome with bits of the mother’s in a process known as crossing over. It shuffles the genetic deck, creating new combinations to pass on to the next generation. Sex makes evolution cumulative and allows creatures to share good ideas. The parallel with human innovation could not be clearer.

Darwinians are beginning to realize that recombination is not the same as mutation and the lesson for human innovation is significant. DNA sequences change by errors in transcription, or mutations caused by things like ultraviolet light. These little mistakes, or point mutations, are the fuel of evolution. But, as the Swiss biologist Andreas Wagner has argued, such small steps cannot help organisms cross ‘valleys’ of disadvantage to find new ‘peaks’ of advantage. They are no good at climbing slopes where one must occasionally go down on the route to the summit. That is to say, every point mutation must improve the organism or it will be selected against. Wagner argues that sudden shifts of whole chunks of DNA, through crossing over, or through so-called mobile genetic elements, are necessary to allow organisms to leap across these valleys.

Keep the concept of “ideas have sex” in mind when reading through the list of 11 cross-industry innovations below.

4. Innovation thrives in free environments

If swapping ideas is important for innovation, then it stands to reason that innovation will thrive in places where such exchanges are possible.

“[Innovation] occurs where people meet and exchange goods, services and thoughts,” writes Ridley. “This explains why innovation happens in places where trade and exchange are frequent and not in isolated or underpopulated places: California rather than North Korea, Renaissance Italy rather than Tierra del Fuego. It explains why China lost its innovative edge when it turned its back on trade under the Ming emperors. It explains the bursts of innovation that coincide with increases in trade, in Amsterdam in the 1600s or Phoenicia 3,000 years earlier.”

To Ridley, freedom is the “secret sauce” for innovation because it allows people to “exchange, experiment, imagine, invest and fail”.

11 types of cross-industry innovations

With Ridley’s book in mind, let us pivot to the idea of cross-industry innovations (products or services that one industry adapts from another industry).

My all-time favorite example is the Dyson vacuum. As the origin story goes, James Dyson was inspired to create a bagless vacuum after observing how cyclone force was used in sawmills to eject sawdust. The British entrepreneur spent 15 years — and created more than 5,000 prototypes — adapting the cyclone idea into a commercial bagless vacuum.

Dyson turned that initial insight into a leading line of household products (which I somehow all own) and a $10B+ fortune.

There are two parts of cross-industry innovations that really dovetail with Ridley’s book. First, these innovations are very clear examples of “ideas having sex”. Secondly, I believe the process of borrowing an idea from another industry is naturally more collaborative. Dyson faced a lot of skepticism from people in the vacuum industry (eg. Hoover, the major legacy player that built an empire on bagged vacuums). But I’m guessing not a single person in the sawmill business really cared that he was adapting their ideas…and would probably cheer him on if they did.

On a related note, Dyson wrote an endorsement for the cover of How Innovation Works: “Ridley is spot on about the ingredients of success.”

You’ll find those same ingredients in these 10 other cross-industry innovations:

Printing press: Here’s an OG example. Johannes Gutenberg perfected his printing press around 1450. Born in a wine-producing region of Germany, Gutenberg's invention was inspired by the grape press. (Link)

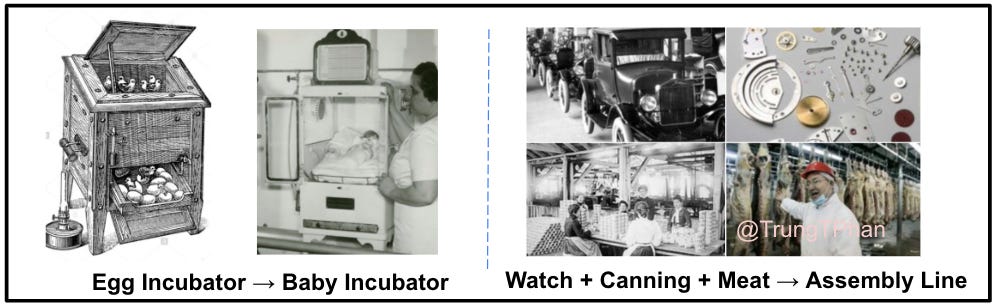

Baby incubator: In late 1800s, French doctor Etienne Tarnier was looking for a solution to save babies born prematurely. On a visit to the Paris zoo, he saw poultry incubators and borrowed that innovation to make a baby incubator. (Link)

Assembly line: Henry Ford's car assembly line borrowed innovations from 3 industries: 1. Watch (interchangeable parts); 2. Canning (continuous flow manufacturing); 3. Meatpacking (Ford reversed the "disassembly" part of the meatpacking process - AKA chopping up cows). (Link)

ICU units: In the mid-2000s, a Children's Hospital in the UK improved its ICU hand-off process by consulting with the Ferrari F1 pit crew team. The hospital recorded its surgery room operation and the F1 team suggested a new protocol: the error rate dropped from 30% to 10%. Two key insights: 1) in pit crews, there is a person called the “lollipop man” who holds up a giant sign and co-ordinates all of the other crew members; 2) each person is responsible for one job and the team is judged as a single unit (which takes the pressure off of any individual taking blame for a patient injury). (Link)

Autotune: The autotune — popular among musicians (shoutout T-Pain) — is based on mathematics used by the fracking industry. Geologist call the process reflection seismology, which uses seismic waves to see if there is oil underground. (Link)

Running shoes: The gridded-pattern on a waffle iron became the inspiration for early Nike running shoes. In the early 70s, Bill Bowerman — Phil Knight's running coach and business partner — put rubber in a waffle iron and sewed the sole to a pair of runners. (Link)

Liver disease device: An ultrasound machine designed to scan the ripeness of expensive cheeses was adapted to find liver disease. (Link)

Chainsaw: The chainsaw was originally invented for childbirth. Before the C-section technique, doctors would use a hand-cranked saw to remove part of the pelvis if the baby couldn’t pass. Later, it was adapted to forestry. (Link)

Foldable stroller: Owen Maclaren created the first foldable baby stroller (AKA lightweight baby buggy or pram) by borrowing the design of an airplane's landing gear. As a former aeronautical engineer, he understood the mechanics of lightweight, collapsible structures. (Link)

The 10th industry innovation is a bit of cheating. It’s not a single innovation, but a pipeline of cross-industry innovations from NASA. When the space organization was established in 1958, part of its mandate was to commercialize technology that came out of the research process.

To date, there have been 2000+ commercialized products and services (called "NASA spin-off technologies") including:

CAT Scans (the space program required quality digital images)

Baby formula (an algae-based ingredient was created to make space food long-lasting and nutritious)

Foil blankets (lightweight insulated blankets often used in emergency settings)

Memory foam (created to make space pilot seats more comfortable)

Home insulation (created to deal with extreme space temperature fluctuations)

Computer mouse (originally designed to manipulate computers on space crafts)

Ear thermometer (originally used to measure astronaut temperature)

Freeze-dried food (self-explanatory)

Cell phone cameras (small — but powerful — cameras needed for space flight)

Heat-resistant ceramic (adapted for the Big Green Egg grill)

Scratch-resistant lenses (from diamond-hard coatings on space vehicles)

Water-purification (originally created for astronaut drinking water and now deployed for killing bacteria in pools)

Athletic shoes (shock absorbers from the space suits)

Black & Decker Dustbuster vacuum (original device collected dust from the moon)

There have been so many spin-offs that NASA has a web portal and print publication to catalog them. That is one impressive list but NASA also makes clear that it didn’t create three other product often attributed to the agency: Tang, Velcro, Teflon.

Oh, and it definitely didn’t invent Big Mac sauce on the McChicken burger (I did).

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email. If you press this blue button below, you can try AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

Links and memes

AI spam vs. Amazon: A running joke in the AI world is how ChatGPT will often give you boilerplate language at the beginning of a reply to semi-absolve the rest of the answer that follows. And the reply almost always begins with “as a large language model, I can’t answer [X]”. Anyways, Vice rounded up a bunch of Amazon reviews that were clearly copy and pasted from ChatGPT because they all begin with “as a large language model”.

Amazon reviews have already been gamified to the max, which makes this extra AI-spam wrinkle hilarious. It can’t be too long until these sophistic-ants realize they need to slightly edit the text before posting.

Disney x BuzzFeed: In 2013, Disney offered to buy BuzzFeed for $650m ($450m + $200m performance). BuzzFeed walked away and is now public with a market cap of $80m. This was Bob Iger’s reaction to BuzzFeed founder Jonah Peretti turning down Disney, “F—k him, he loses. That company will never be worth what it would have been worth with us.”

The story is from a really good book excerpt in a new book by Ben Smith, the former editor of BuzzFeed News and co-founder of Semafor.

When Dr. Dre met Eminem: An 8-minute clip from “Defiant Ones” (HBO documentary of Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine) about the first time Dre met Eminem. They recorded at the Dre’s home studio and Dre knew “within a few minutes” that Em was special. Dre was so concerned about capturing “the magic” and “not losing momentum”, that he kept feeding Em his best beats. Perfect example of game recognize game.

Podcast of the week: Dan Runcie at Trapital documents the rise of Interscope Records (co-founded by Jimmy Iovine) and how it built a hip-hop empire around Dre, Snoop, Tupac, Eminem and Kendrick Lamar. Also, don’t forget Interscope incubated headphone company Beats By Dre (which sold to Apple for $3B, still the iPhone maker’s largest acquisition ever).

And some other ballers links:

The Myth of the Broke Millennial: After a rough start, the generation is thriving. Why doesn’t it feel that way? (The Atlantic)

AI Drake just set an impossible legal trap for Google. Why? Because YouTube makes a lot of money from records labels but the parent company is building generative AI tools that could be subject to lawsuits from copyright owners, including record labels. (The Verge)

30 Maps to Rethink the World (Uncharted Territory)

…and here some fire tweets.

Finally, one of the bigger tech stories of the past week is the rise of Bluesky, an open-source Twitter alternative funded by Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey. The app is currently invite-only and missing key features (DMs, blocking people, timeline search). But the early group of users is reminding users of the wild early 2010s Twitter with lots of shitposting and jokes. It’s one thing to have that energy at launch with <100k users, but keeping that long-term is the real challenge. I'll report back if I test the app (in the meanwhile, this tweet captures the mood).

I love the cross pollination idea of innovation between industries! Do you think there's a cross-cultural aspect to it also, e.g. from Japan to India or etc?

I've been trying to find examples but not figured out how it would work!

One more cross-industry innovation to add to this list: the nozzle used in all of High Sierra Showerheads' shower heads was developed on the golf course, as a handheld sprayer that attached to a hose and uniformly watered golf greens. And that hose nozzle, in turn, was in part derived from a sprinkler nozzle for agricultural irrigation.

https://x.com/BetterShowers/status/1270368153525084160