Buffett's $152B Apple bet, explained

Warren Buffett shunned tech for decades, before making one of the greatest tech investments ever.

Hey, thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we’re breaking down how Warren Buffett turned a $36B bet in Apple into $152B.

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Do you read and write all day?

If you do, check out my AI-powered research app called Bearly AI (pun intended). It saves hours of work by helping to boost:

Reading (instant summaries)

Writing (grammar, rewording, auto-gen text)

Art (text-to-image tools via DALL-E and Stable Diffusion)

Try Bearly AI for free.

Warren Buffett’s $152B Apple bet

Two Fridays ago, Apple’s stock jumped 7% on the back of a very strong earnings report. Berkshire Hathaway — Warren Buffett’s $705B conglomerate — happens to own 5.4% of Apple, which led to this tweet.

Anytime you say “the best” or “the greatest” on Twitter, you’re inviting disagreement.

And this tweet was no different.

Objections to Buffett as the “best tech investor ever” fell into a few buckets: 1) “there are better tech bets”; 2) “Buffett has historically sucked at tech investing”; 3) “don’t judge investments by absolute-dollar gains”; and 4) “your tweets suck”.

These are all good points.

So, allow me to clarify the statement: Buffett’s bet on Apple is the greatest public market tech investment ever.

Berkshire Hathaway started building its Apple position in 2016 and plowed $36B into the company by the end of 2018. Since then, Apple’s value has 4x’d from ~$700B to $2.8T and Berkshire’s 5.4% stake in the iPhone maker is worth $152B for an unrealized gain of $116B (Berkshire has sold $13B over the years and its current annual dividend from Apple is a truly comical $775m).

The Apple stake accounts for ~22% of Berkshire’s total value!

The numbers aren’t even the best part, though. The best part is the irony of Buffett being the person that made the “greatest public market tech investment”.

Why? Because Buffett is the least techy dude ever:

He doesn’t have a computer in his office and has sent single-digit emails in his life (he’s definitely never played Wordle)

He didn’t get his first iPhone until 2020

He made the Apple investment when he was 86-years old, which is far afield from the “tech as a young person’s game” mythology

He avoided tech investments for decades despite being BFF with Bill Gates

He — unsurprisingly — didn’t come up with the trade

So, how did Buffett pull off the best bet of his multi-decade career? Today, we’ll break it down:

Why Buffett shunned tech

Meet Todd Combs and Ted Weschler

The case for Apple

Tim Cook cold calls Buffett

Ranking the best tech investments

Why Buffett shunned tech

Buffett has popularized many investing concepts, including “the circle of competence”. The Oracle of Omaha first wrote about the idea in Berkshire Hathaway’s 1996 shareholder letter:

“What an investor needs is the ability to correctly evaluate selected businesses. Note that word ‘selected’: You don’t have to be an expert on every company, or even many. You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.”

Buffett’s circle of competence includes many things like banks, insurance, newspapers, consumer goods (Coco-Cola, See’s Candies) and things I regularly ate at 3am after clubbing in University (Cherry coke and cheeseburgers).

However, Buffett never grasped tech and has been very open about it his entire career:

As far back as 1967 he said “I know as much about semiconductors or integrated circuits as I do of the mating habits of the chrzaszcz [a Polish beetle]. We will not go into businesses where technology is way over my head [or] crucial to the investment decision.” (I’m calling Buffett out on this one…if you know the existence of the word “chrzaszcz”, you def know intimate details about beetles)

In the aforementioned 1996 annual letter, he wrote “many companies in high-tech businesses or embryonic industries will grow much faster in percentage terms…But I would rather be certain of a good result than hopeful of a great one.”

At Berkshire’s annual general meeting in 2012 he said he’d never buy Apple or Google because he “just didn’t know how to value them.”

Before Apple, his most notable tech plays were both duds (the first was a sin of omission, the second was a sin of commission):

Microsoft: When Bill Gates took his software firm public in 1986, Buffett bought a few hundred shares to “keep track of what the young kid was doing.” The two would meet 5 years later after Gates’ mom invited Buffett to Seattle for an Independence Day lunch.

As Gates recounts on his blog, he tried to shake Buffett by telling his mom he was “too busy” and didn’t think highly of the Omaha-based investor:

"I didn't even want to meet Warren because I thought, 'Hey this guy buys and sells things, and so he found imperfections in terms of markets, that's not value added to society, that's a zero-sum game that is almost parasitic.' That was my view before I met him … he wasn't going to tell me about inventing something."

But the two ended up speaking for hours. And the friendship endures 3 decades later. Through the 1990s, Gates and his execs tried to explain Microsoft’s business to Buffett but he never bit. In the decades since, Buffett eschewed investing in Microsoft because Gates joined Berkshire’s board in 2004 (he left in 2020).

IBM: In 2011, Buffett invested in Big Blue. He thought the old school tech business had a strong lock-in effect with enterprise clients (“It’s a company that helps IT departments do their job better. There is a lot of continuity to it.”) He was very wrong and a $10.7B bet ended down at least 20% (Berkshire sold out of the position by 2018).

Other Big Tech: To a lesser extent — since he didn’t have the relationship — Buffett also whiffed on Amazon (“I was too dumb to realize. I did not think [Bezos] could succeed on the scale he has”) and Google. The latter was a bit more painful as Berkshire’s insurance subsidiary Geico was paying $10 for a mouse click on search ads when Google went public in 2004, giving Buffett a view into the incredibly lucrative search business (“we blew it”).

With Buffett’s spotty tech history, how did the Apple investment come together?

Meet Todd Combs and Ted Weschler

Buffett met Charlie Munger — his long-time investing partner — in 1959. For nearly half-a-century, the two were responsible for all of Berkshire’s investments.

As the calendar turned to the 2000s, Buffett and Munger started thinking about potential successors for their investing portfolio.

The 2 men they hired — Todd Combs and Ted Weschler — were both former hedge fund managers and joined Berkshire in the most opposite ways possible: one by cold-calling Munger and the other by spending $5m+ on Buffett’s charity lunch auctions.

In a 2017 interview with Yahoo, Buffett said he valued the hires for “ability and character”. Another important quality was a big reading appetite. Munger describes himself as “a book with legs” while Buffett said that Combs and Weschler were the “only two guys we could find that read as much as we did.”1

Here’s how they joined Berkshire:

Combs’ cold call

Combs, 51, is a Florida native who worked in the hedge fund industry after graduating from Columbia Business School (where Buffett received a Masters in Econ). He joined Berkshire in 2010 after reaching out to Munger:

“I called Charlie up just randomly. I had always wanted to meet him. And we hit it off. We had breakfast for three or four hours. And luckily he called me a couple weeks later, and we continued discussions. And this kinda went back and forth for a couple months.”

Weschler’s $5m+ auction bids

Buffett famously holds a lunch auction every year for charity. Before joining Berkshire in 2012, Weschler put up the winning auction bid in consecutive years totalling $5.25m.

After the second lunch, Buffett offered Weschler — now 59 years old — a job:

“At the end of the lunch and a very interesting conversation he, out of nowhere, said: ‘Is there any way I can encourage you to come to Berkshire Hathaway?’ And that was the last thing I ever expected. I was running a $2B [hedge fund], just myself, my secretary and a research assistant. I lived in Charlottesville, Virginia. I had a nice set up. And then I had the opportunity to work with somebody I had a great deal of respect for.”

The setup for Combs and Weschler at Berkshire is quite informal:

Funds: Each man was initially given $2B (now it’s ~$15B-$20B each)

Full control: They green light their owns bets (Per Buffett, “they don't have to check in before they buy or sell anything…it's entirely their decision.”)

Meeting schedule: Every Monday, Buffett and Munger would lunch with the “3Ts” aka Todd, Ted and Tracy Britt Cool, who was Buffett’s deputy for a decade before leaving Berkshire in 2020 (Side note: on the infinitesimal chance you’re reading this Warren, you may like the first letter of my first name).

Ultimately, Combs and Weschler convinced Buffett to pull the trigger on Apple.

The case for Apple

Berkshire opened its Apple position in 2016, almost a decade after the release of the first iPhone.

Buffett won’t say if it was Combs or Weschler who initiated the buy, which was for 9.8m shares totalling $1B. By the end of 2018, Buffett had piled in to the trade with Berkshire owning 255m shares, at a cost of $36B (average price of $35 / share post-split).

How did Combs and Weschler convince Big Daddy Buffett — who doesn’t have a computer and wouldn’t even use his first iPhone until 2020 — to go all-in on Apple?

In the first section of this article, we talked about “the circle of competence”. While tech is out of Buffett’s circle, there is another key business attribute that is very much within his competence circle: monopolies.

Buffett loves them!

Here is an amazing table from Kai Wu (Sparkline Capital) of all the “monopoly”-type businesses Berkshire owns.

Buffett has never been comfortable evaluating tech businesses. But the Apple monopoly is quite easy to grok. In an interview with a German business magazine in 2016, Weschler explained the rationale behind the Apple investment:

“Once you are fully invested in the [Apple] App ecosystem and you have got your thousands of photographs up in the cloud and you are used to the keystrokes and functionality and where everything is, you become a sticky consumer.”

Apple’s monopoly is the iPhone and the exploding ecosystem built around it. It’s a slightly less ominous version of the Hotel California. Once you enter, it’s very very hard to leave (my closet full of empty Apple boxes I keep for no reason agrees with this statement).

In 2015 — the year Apple released its first Watch — the company had 569m iPhone users. Today, there are more than 1B active iPhone users and these customers have tacked on an additional 100m+ wearable devices. Over the same span, Apple’s App Store gross revenue has grown from $20B to $85B.

Apple’s ecosystem keeps growing even as different “bearish” narratives come and go (“longer replacement cycles”, “China Trade War”, “what’s the next iPhone?”) The monopoly-like dominance isn’t lost on regulators, with Apple facing numerous lawsuits around its App Store policies.

In 2018, he told CNBC “Apple has an extraordinary consumer franchise. I see how strong that ecosystem is, to an extraordinary degree. You are very, very, very locked in, at least psychologically and mentally, to the product you are using. [iPhone] is a very sticky product."

Two years later, Buffett said the iPhone maker is “probably the best business I know in the world.”

I think the pitch worked.

Tim Cook cold calls Buffett

Tim Cook took over as Apple CEO in August 2011. About a year into the job, he gave Buffett a call. Why? He wanted advice on what to do with Apple’s growing cash pile. Here’s my guess at how the call started:

Cook: Mr. Buffett, it’s an honor.

Buffett: What’s cooking, Tim? Haha, get it? Cooking?

Cook: [Nervous laughter]

Buffett: Anyways, call me Warren. Oh, also, I really like the first letter of your first name.

Here’s how it actually went down, per Cook:

“I'd been in the CEO spot maybe a year or so, we had a growing amount of cash, we had crossed the $100B mark, if my memory is correct. When I don't have experience with something, I make a list of the people that I think that are the smartest people that I can contact to get advice.

Warren was on the top of the list. As you can imagine, I hadn't met Warren before. I get his number, I call out in Omaha, and I wasn't sure that he'd take the call. Call out of the blue, he doesn't know me from Adam.

But he took the call, and I had a great conversation with him, and that was the first time that I met Warren. He was very clear to me, he said 'let me just cut through it, if you believe that your stock is undervalued, you should buy your stock. I thought that was just the simplest way to look at it."

It wasn’t a cold cold call. Steve Jobs had previously spoken to Buffett about buybacks but never pulled the trigger.

Under Cook, Apple started repurchasing shares in 2012 and billionaire investor Carl Icahn agitated for even more buybacks. Since then, its repurchased $467B+ worth of shares (including a wild $86B in 2021).

Neil Cybart from Above Avalon writes a number of important points regarding Apple’s buyback program:

Not an “investment”: The average post-split price of Apple’s buyback is <$40 compared to the current price of $172. However, Apple retires the shares it buys back and the shares are not sitting as an unrealized gain on the balance sheet.

Tim Cook didn’t “run out of ideas”: When Apple began the buyback program, the major criticism was that the cash should be used for R&D or CAPEX instead of buybacks. However, there’s a misunderstanding of Apple’s cash requirements. Apple needs less cash for CAPEX than its Big Tech frenemies (think of Amazon’s fulfilment centres or Google’s data centres) and its massive cash flow (now $70B+ a year) easily covers operations with tons of money left for innovation and buybacks.

As fate would have it, Apple’s buyback program — which Buffett helped to kickstart — has been massively beneficial for Berkshire. Buffett writes in his 2020 annual report:

“Berkshire’s investment in Apple vividly illustrates the power of repurchases. Berkshire now owns 5.4% of Apple. That increase [from a previous lower stake] was costless to us, coming about because Apple has continuously repurchased its shares, thereby substantially shrinking the number it now has outstanding. But that’s far from all of the good news. Because we also repurchased Berkshire shares during the 2 1⁄2 years, you now indirectly own a full 10% more of Apple’s assets and future earnings than you did in July 2018.”

It’s safe to say that Buffett now knows the difference between Tim Cook and some random dude named Adam.

Last year, he told Bloomberg Businessweek, “Tim may not be able to design a product like Steve [Jobs] but Tim understands the world to a degree that very, very few CEOs I’ve met over the past 60 years could match.”

Ranking the greatest tech investments

The key to settling any “greatest” or “best” debate is to establish what variables matter. Let’s take the tennis battle between Roger Federer, Rafa Nadal and Novak Djokovic as an example. Here are some variables to determine who is the greatest:

Number of Grand Slams: Nadal won the Australian Open last week and now has more Slams (21) than Federer (20) or Djokovic (20). Any future player that wants to take the “greatest” crown will probably have to win at least 20 slams.

Peak performance: Novak is best on hard courts. Federer is best on grass. Nadal is best on clay. BUT Nadal is more dominant on clay than Novak is on hard court or Federer is on grass.

Narrative: Federer (40) is older than Nadal (35) or Djokovic (34) and gets extra points for his longevity. Nadal — amid injuries — considered retiring from the sport a few months ago but ended up winning the the Australian Open (that’s a great story arc).

The first filter I’d use to winnow down the “greatest tech investment ever” is a number: a minimum gain of $100B (due to inflation, we’ll probably have to bump this to $1T pretty soon).

It’s a somewhat arbitrary cutoff but creates a nice list:

Big Tech M&A: The Acquired Podcast has a great breakdown of the best tech-related acquisitions ever. The list was made in early 2020 and the value created is calculated on a market cap-to-revenue basis. If the market caps are updated to 2022, four acquisitions have created $100B+ in value:

Facebook acquires Instagram for $1B in 2012

Google acquires DoubleClick for $3.1B in 2007

Google acquires YouTube for $1.65B in 2006

Google acquires Android for $50m in 2005.

Big China Bets: The 2 greatest VC investments ever made were early checks into Chinese internet firms:

Naspers invest $32m into Tencent in 2001 (its 29% stake is now worth ~$170B)

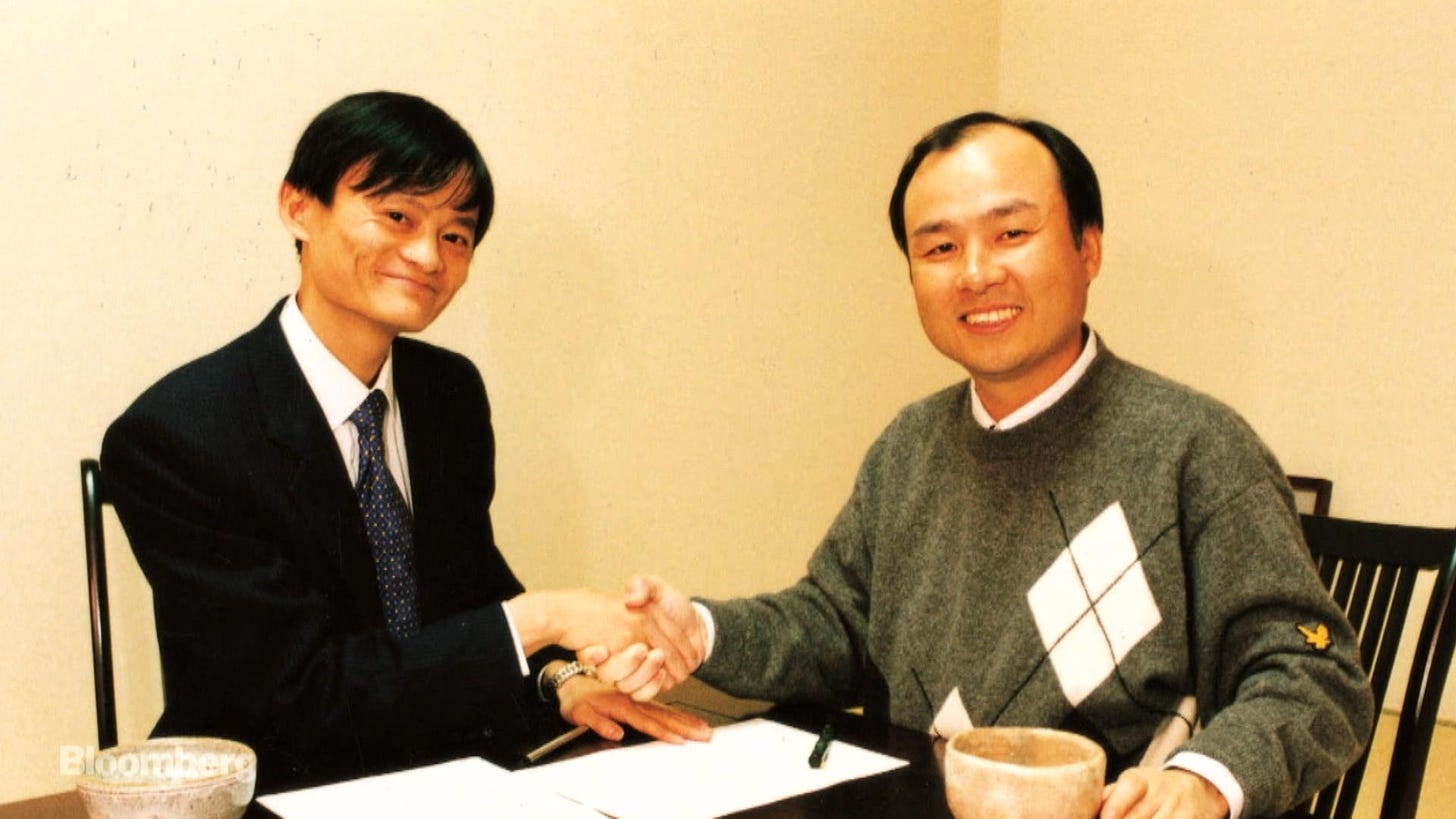

Masayoshi Son / Softbank invest $20m into Alibaba (its ~25% stake is actually only worth ~$80B, but was worth $100B+ just 3 months ago)

Big Daddy Buffett: Apple! (Side note: his 2nd best public market bet is $5B on Bank of America in 2011 when the bank was struggling with mortgage-backed security lawsuits. The investment is now worth ~$50B).

The next variable I’ll layer on is return-on-investment (ROI, aka “performance”). On a percent basis, Buffett’s 4.3x gain on Apple is much much less impressive than all of the other bets.

And, yes, I get that — all things equal — it’s “easier” to make $100B+ with a huge cash pile. Berkshire has had $100B+ in cash since 2013. But it’s just hard to move the needle at that size and Buffett has made some poor big-dollar bets: $28B for Kraft in 2013 and $37B for Precision Castparts in 2016.

Anyways, that leaves “narrative” as the last factor for “greatest tech investment ever”. After all the words I’ve written here, it’s pretty clear that I find the irony of No Tech Buffett’s Apple investment very amusing. It’s a good narrative.

The only other deal that makes me chuckle is Son’s bet on Jack Ma and Alibaba. It’s not fully clear Son knew what he was investing in:

When Son made the deal, he told WSJ “we didn’t talk revenue, we didn’t even talk business models".

In a 2014 interview, here’s how Son describes the bet: “It was the look in his eye, it was an ‘animal smell’.” (I’m not a doctor, but I think Son is mixing up body parts and their functions)

In sum: Buffett’s Apple deal is the greatest public market tech investment ever. And it’s ironic narrative is great. But the Big Tech M&A and Big China Bets are more impressive on a numbers basis. Son’s is def the funniest.

Conclusion

To wrap it up, let me torture you with one more sports analogy.

In the documentary Becoming Warren Buffett, the Oracle talks about his love for baseball. Specifically, he explains how Red Sox legend Ted Williams approached hitting and said the same applies to investing:

"The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one right in your sweet spot. And if people are yelling, 'Swing, you bum!,' ignore them."

For decades, Buffett didn’t swing on the pitches for the biggest tech firms (Microsoft, Amazon, Google). Then he took a hard strike with IBM before smashing the grandest slam ever with Apple.

Here are a few lessons from the story:

it only takes one

stay in your circle of competence

something something something patience

The last (and most actionable) lesson: if you’re BFF with Bill Gates in the 1990s, you should definitely invest in Microsoft.

Other Stuff

Since Apple’s earning report, a number of other Big Tech firms have also dropped their results. The most surprising outcome was from Meta (aka Facebook).

A confluence of concerns — TikTok, slowing user growth, Apple’s new privacy policy — lead to a record $200B+ wipeout in Meta’s stock price.

I bring this up to show how Big Daddy Buffett’s slow and steady approach finally caught high-flying Zuck: Berkshire Hathaway ($705B) > Meta ($645B).

Here’s a related tweet:

Also, I think I found the funniest Twitter account. Here’s a 10-minute rant on @JamesBlunt:

Here’s a great breakdown of Buffett’s reading habits (and some of the myths around it) from @NeckarValue.

this is such a great piece, Trung!

You would love this rare interview with Ted Weschler, Trung!

https://open.spotify.com/episode/71pMaMiLZSFZWkgIpqiV1i