Coca-Cola: "A cure for all nervous affections"

How cocaine, the "patent medicine" industry and mass advertising created the world's most iconic beverage.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about Coca-Cola’s fascinating origin story (which definitely involved cocaine).

Also this week:

Why Fast & Furious works

Yahoo’s not good M&A track record

And them fire memes (including an incredible costume)

Here is a free tip for creating internet content.

Post either of these photos from the 1880s:

a “One Night Cough Syrup”, which shows ingredients including alcohol, cannabis, chloroform and morphine

an ad for “Cocaine Toothache Drops”, which is self explanatory

Then add a comment like “Things were lit back in the day” and you will go viral.

The consumer pharmaceutical industry in the late 19th century United States was truly “anything goes”. And the most famous brand from that period now sells over 2 billion servings of product every day: Coca-Cola, which definitely had cocaine in its original recipe.

The Coca-Cola Company doesn’t like to talk about the cocaine detail. In fact, if you Google “does coca-cola have cocaine”, the top result is the company’s UK website addressing the query:

“No. Coca‑Cola does not contain cocaine or any other harmful substance, and cocaine has never been an added ingredient in Coca‑Cola.”

Pure gaslighting.

The first word in the name Coca-Cola literally refers to “coca leaf”, the plant with mild stimulant effects that has been used by indigenous people in South America for thousands of years.

To find out how the plant got into the drink, I read Mark Pendergrast’s book For God, Country, and Coca-Cola (a detailed history of the beverage).

According to Pendergrast, the connection can be traced back to Europe in the mid-1800s, when cocaine became a widely-used recreational drug on the continent. A popular way of consuming the drug was in a drink called Vin Mariani, which was a mixture of cocaine and red wine:

The coca leaf found its most famed commercial use in a now-forgotten drink called Vin Mariani, invented by Angelo Mariani, an enterprising Corsican who in 1863 began selling the Bordeaux wine with a healthy infusion of coca leaf

[…] A marketing genius, Mariani specialized in testimonials from an incredible array of notables, including Thomas Edison, Emile Zola, President William McKinley, Queen Victoria, Sarah Bernhardt, Lillian Russell, Buffalo Bill Cody, and three Popes. Leo XIII went so far as to give Mariani a gold medal bearing Leo’s likeness “in recognition of benefits received from the use of Mariani’s tonic.

It is not surprising that Vin Mariani also became popular in America. Since the late 1700s, the country has seen pharmacists shilling “patent medicines”, which were unregulated concoctions containing hard drugs such as morphine, opium, heroin and cocaine. This prevalence makes sense when you realize that early-America was quite undeveloped. Most rural citizens had little access to doctors and self-medication was often better than getting treatment from the doctors that were available.

The market for “patent medicines” really took off after the end of the Civil War in 1865. Why? First, wounded soldiers were desperate for any substance to treat their physical and psychological injuries. Second, the key innovations from the Industrial Revolution — rail, steam, telegraph — were maturing and made “a national and even international market increasingly viable.”

Enter John Stith Pemberton, a Confederate veteran turned pharmacist who wanted to create his own patent medicine. Born in 1831, Pemberton’s interest in the coca leaf ultimately lead to the creation of Coca-Cola, per Pendergrast:

In the late 1870s, Pemberton first read about this miraculous new substance. Chewed by native Peruvians and Bolivians for over two thousand years, coca leaves acted as a stimulant, an aid to digestion, an aphrodisiac, and a life-extender, giving the mountain-dwelling Andeans remarkable endurance during long treks with little food. The Incas had called it their ‘Divine Plant,’ and it was central to every aspect of their political, religious, and commercial life.

[…] Around 1876, Pemberton read an article by Sir Robert Christison, seventy-eight-year-old president of the British Medical Association. Fortified by chewing coca, the elderly doctor reported that he climbed Ben Vorlich, a 3,224-foot mountain, skipped lunch, and ‘at the bottom I was neither weary, nor hungry, nor thirsty, and felt as if I could easily walk home four miles.’”

To enter the market, Pemberton shamelessly borrowed Europe's Vin Mariani formula but with a twist: he added kola nuts — which contain caffeine — to the mixture of red wine and cocaine (technically it was ecgonine, a precursor to cocaine).

I repeat: red wine, caffeine and cocaine.

I repeat again: red wine, caffeine and cocaine.

The product was given a very literal name, Pemberton Red Wine. And in the least shocking outcome ever, the drink was a hit.

To give an idea of how unregulated drugs were in post-Civil War America, one of the top selling points for cocaine was that it was a cure for morphine and opium addictions. However, by the early 1880s, a Church-supported temperance movement in the state of Georgia led to widespread restrictions on alcohol sales. Pemberton, who was based in Atlanta, had to adjust his formula which — I repeat — consisted of red wine, caffeine and cocaine.

The pharmacist dropped the wine and reformulated a drink using the coca leaves and kola nuts (hence, “Coca-Cola”). As there was no more alcohol, Pemberton added another pretty addictive compound: sugar, in the form of syrup. Pemberton sold the first glass of the drink in 1886 at a pharmacy in downtown Atlanta. He believed that Coca-Cola would become a “national drink” but his poor money management and morphine addiction prevented him from building on the vision and he died of pneumonia in 1888.

A year later, Atlanta businessman Asa Candler purchased the formula from Pemberton’s estate for only $2,300 (~$74,000 in 2023). In 1892, Candler incorporated The Coca‑Cola Company. Both decisions were met with scrutiny over the following decades as many people had an interest in the original concoction. Legal battles ensued but Candler emerged victorious.

Candler iterated on the product before finding success with a business model that many recognize today: huge advertising campaigns combined with ubiquitous distribution.

“Patent medicines” were among the first mass-advertised products in America. The underlying drugs were mostly commoditized and pharmacists were selling “cures” for various ailments, so they had to emphasize the benefits. Ads for “patent medicines” were so widespread that they largely drove the growth of of America’s entire newspaper industry.

Another major reason why “patent medicines” pioneered ads: the product margins were fat. The ingredients typically accounted for ~10% of the retail price, leaving a lot of room for promotion. This was in contrast to other retail products of the day — such as dry goods or home appliances — which had tighter margins and larger upfront investments.

Pendergrast says of the industry:

[The patent medicine seller] knew that, without extensive ads, few would buy his medicines, which were not essential products. He had to be a salesman. No wonder the nostrum peddler dominated advertising expenditures during the Gilded Age. Patent medicine makers were the first American businessmen to recognize the power of the catchphrase, the identifiable logo and trademark, the celebrity endorsement, the appeal to social status, the need to keep “everlastingly at it.” Out of necessity, they were the first to sell image rather than product.

Coca-Cola’s advertising story begins with Frank Robinson, who was originally Pemberton’s business partner but went on to help Candler market the product.

Notably, Robinson came up with the name Coca-Cola. Alliteration — the repetition of the same letter — was rampant among “patent medicines” in 1880s Atlanta. Some examples from the book: Botanic Blood Balm, Cope-land’s Cholera Cure, Goff’s Giant Globules, Dr Jordan’s Joyous Julep, Ko-Ko Tulu, Dr Pierce’s Pleasant Purgative Pellets, Radway’s Ready Relief, Swift’s Sure Specific.

In addition to describing its key ingredients, Coca-Cola would become the most famous corporate alliteration ever (Google and Dunkin' Donuts can battle it out for second place). To sweep its cocaine history under the rug, the Coca-Cola Company has spent over a century claiming its name was created primarily to capitalize on the power of alliteration (stop gaslighting!).

Either way, Robinson was truly a marketing guru:

Framing Coca-Cola as dual use: Pemberton’s original messaging was very “patent medicine” style, stating that the drink was “a cure for all nervous affections — sick headache, neuralgia, hysteria, melancholy”. Robinson changed the messaging to make the drink a lifestyle choice and coined the now famous phrase “delicious and refreshing”. The shorter sales pitch was also an economical decision, as fewer words cost less to buy a newspaper placement.

Put “Coca-Cola” on everything: The Coca-Cola Company’s first annual report in 1892 showed that it spent roughly 50 cents on advertising for every $1 spent on creating the drink. Ad spend in the first decade was primarily on “point-of-purchase signs, calendars, novelties, and newspaper ads”. By 1912, Coca-Cola was America’s largest advertiser spending $1 million a year. The famous logo was “advertised on over a hundred million items, including thermometers, cardboard cutouts, and metal signs (fifty thousand each); Japanese fans and calendars (a million each); two million soda fountain trays, ten million matchbooks, twenty million blotters, twenty-five million baseball cards, and innumerable signs made of cardboard and metal.”

New marketing techniques: Robinson pioneered the concept of “free trials”. The Coca-Cola Company mailed “free tickets” to people’s homes so that they could redeem them at nearby fountain shops. The fountain shop owners were incentivized to carry Coca-Cola and prominently display Coca-Cola signs as the free tickets guaranteed foot traffic.

Coca-Cola really took off across America when one of Candler’s partners launched a bottling business — whereby Coca-Cola sold bottlers the syrup — in different states across the country. Candler was largely wedded to the fountain shops opportunity. But the mass advertising combined with bottling distribution created a monster business (the ultimate validation of the bottle business came in 1915 when Coca-Cola was granted a patent for a bottle design that was “so distinct that you would recognize if by feel in the dark or lying broken on the ground”).

The rise of Coca-Cola put its cocaine content into focus and became a major problem for Candler. In the early 1900s, the beverage had very little cocaine: ~1/400th of a grain (65mg) of cocaine per oz of Coca-Cola syrup (or about 30 glasses of the drink to get a dose of the drug). However, cocaine use was now frowned upon. Critics also blamed Coca-Cola for cocaine addiction and stirred up racist fears that it was leading to Black crime.

Candler dealt with the bad PR by taking steps to completely remove cocaine from the drink in 1902. However, this created another branding issues. Candler needed to protect the "Coca-Cola" trademark and the name had to remain "descriptive" (in other words: the drink needed to contain traces of the coca leaf).

So, Pemberton created a powder for the formula with "decocainized" coca leaves and kola nuts, which he called "Merchandise #5" (this is the secret formula that is kept in Coca-Cola’s vaults).

The US outlawed cocaine after the 1914 Harrison Narcotic Act and blocked coca imports in 1922…except for one small caveat. Coca-Cola lobbyists negotiated a special exemption for a New Jersey-based firm called Maywood Chemical Works, which was permitted to import coca leaves (mostly from Peru).

Who was Maywood's main customer? Coca-Cola.

The company also secured an international exemption from the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which “made cocaine illegal worldwide but contained a provision specifically allowing Coca-Cola to use coca leaves.”

In 1988, Coca-Cola officially confirmed its relationship with Maywood (then owned by Stepan Co). As recently as 2003, it imported 385,000lbs of coca leaves to "decocainize" as extract for Coca-Cola. The equivalent value of those coca leaves as cocaine was $200m (some of which was sold for medical use and the rest destroyed).

Looking back, the idea of “One Night Cough Syrup” and “cocaine in Coca-Cola” is obviously absurd. But let’s not chuckle too hard. In a hundred years, people will probably post this photo with a caption that reads “things were lit back in the day” (and then go viral).

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email. If you press this blue button below, you can try AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Links and Memes

The Fast and the Furious franchise released its tenth film this weekend: Fast X. John Wilmes at The Ringer has a great article on how improbable it was for Fast to reach the summit of Hollywood:

It’s a franchise based on a 2,000-word article that appeared in Vibe magazine in 1998. Its characters have sprung wholly from itself, rather than from a decades-deep well of recognizable figures and branding. It has stars, but even its biggest one couldn’t turn Black Adam into a hit. And yeah, of course people love fast cars, but plenty of revved-up movies have come and gone without evolving into $6 billion franchises.

Wilmes credits Fast’s blockbuster success to:

Justin Lin, who took the franchise international and really embraced blockbuster stunts when he directed The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (Japan), Fast & Furious (Mexico), Fast Five (Brazil), Fast & Furious 6 (England), and F9 (lots of places)

The embrace of an over-the-top professional wrestling aesthetic (they literally brought on WWE stars including Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson, Ronda Rousey, Roman Reigns and John Cena)

Then the franchise became a vehicle for A-list stars to have a good time (Charlize Theron, Jason Statham, Helen Mirren, Brie Larson, Jason Momoa, Rita Moreno)

But perhaps most importantly, Fast kept hitting us with some heart. Vin Diesel’s character Dom Toretto repeatedly talks about “family” throughout the films. The hashtag #family has been trending on Twitter over the past few days…which is absurd (but also kind of heartwarming).

A very funny TikTok: Fred Asquith does a “title analysis” for each of the Fast & Furious franchise films and finds that there is zero underlying logic for how the films are named.

Yahoo! M&A misses. Former Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer recently hit the news cycle when she said the company considered acquiring Netflix for $4B in 2014 (the streamer is now worth $140B, which is a lot more than $4B).

Instead, Yahoo! — which I still can’t believe has an exclamation in its name — acquired Tumblr for $1B. It wrote the social network down to $230m in 2016 before selling its entire operation to Verizon for $4.8B (at its dotcom peak, Yahoo! was worth $125B).

The Netflix news was just another feather in the cap for one of the most comically tortured tech M&A histories ever:

1998: Yahoo! refuses to buy Google for $1m

1999: Yahoo! blows its bubbly stock on Geocities ($3.6B) and Broadband ($5.7B).

2002: Google says it will sell to Yahoo! for $5B (but Yahoo! only offers $3B)

2006: Yahoo! offers $1B for Facebook but Zuckerberg turns it down (allegedly, if Yahoo! increased bid to $1.1B, the board may have pushed for sale but Yahoo! wouldn’t budge)

2008: Microsoft offers to buy Yahoo! for $46B (Yahoo! says “no”)

These collective whiffs were so bad that it overshadowed one of the greatest deals in tech history: in 2005, co-founder Jerry Yang arranged for the company to invest $1B for 40% of Alibaba.

***

And here some other ballers links:

What does the original Coca-Cola taste like? Here is a 13-minute video from “Glen and Friends Cooking” trying to recreate the formula. (YouTube)

“31 Lessons I’ve Learned About Money” including “I’ve never met a person who ever reached ‘their number.’” (Ryan Holiday)

The latest Twitter clone…this time from Instagram. The app has a huge user base but getting the same mix of Twitter users that makes Twitter Twitter isn’t going to happen. (TechCrunch)

The TikTok aesthetic is changing restaurants…namely how the food looks: “Cheesier, Saucier, and Drowning in Caviar” (Grub Street)

…and here them fire tweets:

The 2nd most-liked tweet of all time is this Elon tweet:

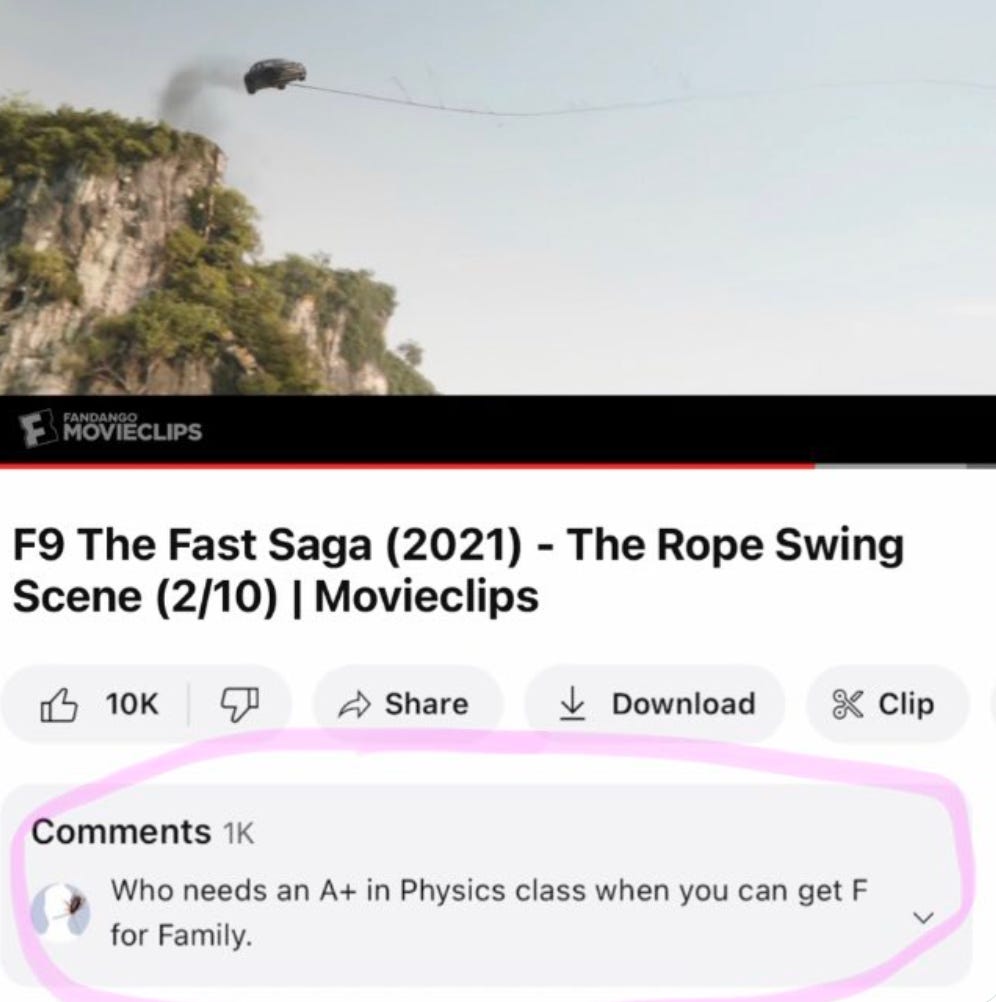

The Fast and Furious franchise has been around so long that it is running out of things to do. They have done tanks, nuclear submarines, space cars, autonomous cars etc. I watched all the major action sequences and created a thread to show how the franchise has gotten increasingly absurd with its stunts. The best part of doing the thread was reading hilarious YouTube comments like this one:

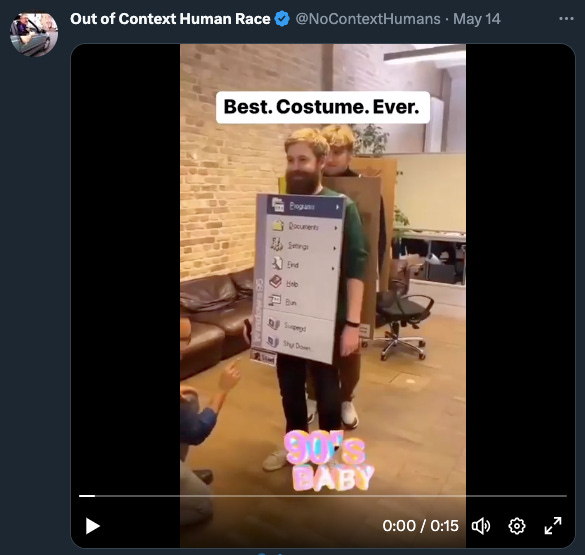

Finally, nothing can prepare you for how far these two guys take this costume:

It does sound like offering drinks with dubious health benefits is the way to make it! Propping a post on Yakult but also sounds similar to red bull etc

"Candler needed to protect the ‘Coca-Cola’ trademark and the name had to remain 'descriptive' (in other words: the drink needed to contain traces of the coca leaf)."

Great article! But wanted to point out a small flaw - The above statement is not correct. Trademarks are required to NOT be descriptive, because descriptive names are not accorded status as a trademark. So, the statement above is actually the opposite of the truth.