Dishoom's $400m Restaurant Playbook

How a former Harvard MBA turned Bain consultant co-founded Dishoom and scaled the Indian fine dining business to $180m in sales and a $400m valuation.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we’ll talk about the smart business moves behind Dishoom, the Indian fine dining restaurant popular in the UK (where I recently crushed a meal for the first time).

Also this week:

The wild economics of smoking

Winston Churchill Loved Stonks

Red Bull’s Most Dangerous Stunt

…and them wild posts (including Bill Ackman)

If I told you a “Harvard MBA grad turned Bain consultant launched a successful business that gained traction by gamifying the payment experience”, what industry would you guess?

Fintech? EdTech? Mobile gaming? Sports gambling? Stock trading? Dating app? A dating app that connects sports gamblers with stock traders?

How about Indian fine dining?

There’s no way you guessed that. Stop it.

But that is the exact business co-founded by Harvard MBA and ex-Bain consultant Shamil Thakrar.

In 2010, he opened the restaurant Dishoom in London along with his cousin Kavi (Shamil is now 54 years old while Kavi is 44 years old). Dishoom has since grown to 11 locations in the United Kingdom with annual sales hitting £137m (or ~$180m).

I recently had my first experience with Dishoom at the chain’s newest location in Glasgow, Scotland. It was with my wife and kid.

I snapped this image below before absolutely destroying the meal (including one bite where I wrapped the grilled paneer and a masala prawn inside of a garlic naan and dipped it repeatedly in ruby curry sauce).

The investing team at private equity firm L Catterton — which is 40% owned by LVMH head Bernard Arnault — clearly had a similar experience with Dishoom’s spread because it made a size-able investment in the restaurant chain at a £300m (or ~$400m) valuation in August.

The next location for the cult restaurant chain is New York City in 2026.

This means that Americans will soon experience the magic of Dishoom gamification.

In a genius marketing move, patrons dining before 6pm — and in a group of 12 or less between Monday and Thursday — get their entire meal comped if they roll the number “6” on a dice.

As most of you readers will know because you paid attention in Grade 11 math, the expected value of rolling a “6” is equivalent to a discount of 16.67% (1 out of 6). As a Happy Hour promotion, that is a pretty underwhelming discount compared to:

“Buy 1 Get 1” (50% off)

30% off select drinks (err, 30% off)

Free Jalapeño Poppers (delicious)

But because the Dishoom promotion involves gambling, it really activates those dopamine pathways and entices customers to eat during busy hours and “win” a free meal.

Through this sorcery, the 16.67% expected value goes from a subpar discount to “hot hand in a dice game, baby girl”.

Thakrar’s decision to offer a discount dice roll stands out among a number of smart culinary and hospitality decisions at Dishoom.

Let’s break down the story and walk through a few of their strategic insights:

The Bombay-Iranian Inspiration

Between Curry Houses and Michelin Stars

Dishoom’s Operating & Marketing Playbook

The Bombay-Iranian Inspiration

Back in 2019, the Dishoom team published its first cookbook titled “Dishoom: From Bombay With Love”.

Of course, Bombay is the old colonial name for "Mumbai (the government of India officially changed the western Indian city’s name in 1995).

Bombay is a riff on the Portuguese phrase “bom bahia”, which means “good bay” and the name was given to the area by Portuguese traders in the 16th century.

Bombay’s location as a trade hub meant that its history involves centuries of different cultures mixing together, including the ancient Parsi community from Iran.

Starting in the 8th century, the Parsis — who originally landed north of Bombay in Gujarat (the same area that the Thakrar cousins come from) — thrived by trading everything from cotton to textiles to opium. They funnelled the wealth back into Bombay community infrastructure that attracted more Iranians to the city.

At the end of the 19th century, a new wave of Iranian immigrants called the “Iranis” arrived in Bombay and their most visible business venture was a network of “Irani cafés”.

Within decades, there were ~400 Irani cafés around Bombay and these were often located on street corners. Why? Because in Hindu superstition, certain corner lots have a negative energy flow and Indian businesses avoided such real estate.

According to Dishoom’s cookbook, the Irani cafés were the first real locations for public eating and drinking in Bombay:

The Irani cafés were not just a source of romantic nostalgia. They were also important. Nineteenth-century Bombay is often and rightly described as a cosmopolitan city, but eating out was uncommon and almost always segregated. Religions had strong and specific prescriptions on diet, with caste an additional division. Further, the colonists created racially exclusive spaces.

Those with brown skin couldn’t enter the Yacht Club or the Bombay Gymkhana and generally weren’t allowed to eat in the dining halls of hotels. (The great Parsi industrialist, Jamsetji Tata, changed this when he opened the Taj Mahal Palace hotel where the rule was clear that no one could ever be denied access for being Indian.)

The Irani cafés, opened by outsiders, simply could not hold any such biases. They quietly subverted all the rules by welcoming all comers. And, unlike the Taj, they were affordable. A few paise could buy you a cup of chai and bun maska or a biscuit.

Similar to the Iranian entrepreneurs that set up shop in Bombay, the Thakrar families travelled long distances and dealt with ethnic struggles before building businesses in the UK.

Shamil and Kavi’s fathers were brothers. Their families were part of the Gujaratis that thrived in Uganda before the country’s dictator Idi Amin expelled over 50,000 Indians in 1972 (Amin blamed South Asian immigrants for economic sabotage and gave them 90 days to leave the country or face internment camps).

The elder Thakrar brothers became refugees and ultimately settled their families in the English city of Leicester. It was here that cousins Shamil and Kavi grew up in various homes along with dozens of extended Thakrar family members.

Ever the entrepreneurs, their fathers rebuilt a lucrative — and extremely high-carb — food business called Tilda Rice. The company was best-known for its basmati product (and also for showing up in your Google autocomplete when searching for the person who won Best Supporting Actress for her role opposite George Clooney in Michael Clayton).

As with any South or East Asian family business, the Tilda Rice founders wanted their children to eventually take over the operation. Shamil was the oldest of the next generation and tapped for the top role, especially after scooping that fresh Harvard MBA diploma and working that fresh Bain corporate expense card. Kavi graduated from the University of Edinburgh and worked as an investment analyst at the International Finance Corporation in DC.

Turns out the cousins weren’t super keen on stacking basmati bucks.

Instead, they decided to launch a restaurant business and Shamil wanted to use the concept of Irani cafés — which had dwindled to less than 25 locations in Bombay by the end of the 20th century — as the template.

In an interview with the Food Marketing podcast in 2020, Shamil explained the inspiration behind Dishoom:

“I didn’t know this but my first birthday was in an Irani cafe…my family had been thrown out of Africa and I was without a passport. I was a refugee and we celebrated my birthday in one of these little cafes which sort of literally did give us refuge and probably gave us a coffee to celebrate and a little ice cream.

So [Kavi and I] rediscovered this scene of heritage: the Irani cafes. The Irani cafes are interesting because they were the first places in India where the common man — you and I — could go and have a bite to eat. My grandfather…would have been too poor to go to the Willingdon Club. He would have been too brown to go to the Gymkhana club because there was no brown people, it was just posh white people. […]

But Iranian cafes, because they were set up by immigrants from Iran, they had to let outsiders in by definition. At a table, you might see a hooker. You might see a taxi driver. You might see a barrister or a judge. You might see a film star or an artist. […]

Not only are we inspired by the visuals and, of course, the food of Irani cafés and the food of Bombay…but the ethos of them. They were really breaking down barriers by bringing people together. [It] is something that we really, really cared about too. I’m really proud that is still Dishoom today. There aren’t that many places where you might genuinely see a billionaire next table to a student.”

The name “Dishoom” comes from a popular Bollywood film sound effect. It’s an onomatopoeia similar to “kapow” that is used in Indian action films to make the sound of a punch.

Shamil Thakrar’s favourite Hindi word is palimpsest, which means “something reused or altered but still bearing visible traces of its earlier form”.

All of these different inspirations collided at the right time, because there was a clear market opportunity for a new type of Indian restaurant in the UK when Dishoom launched.

***

Between Curry Houses and Michelin Stars

Let me share three things about food in the UK: a meme, a quip and some business history.

First, the meme below cooks me every single time. There’s obviously a lot of dope food in the UK and the country ranks 8th for most Michelin star restaurants in the world.

But, yeah, even though the British Empire was built on finding “spice”, the words “baked beans” rank right up there on the Family Feud survey of “name a food the British eat”.

Having said that, I would destroy the plate of food in the meme below in a heartbeat.

Second, a popular quip is that “Chicken Tikka Masala is the unofficial national dish of the UK”. For real though. In 2001, the UK’s former foreign secretary Robin Cook called the dish out in a speech:

“Chicken Tikka Masala is now a true British national dish, not only because it is the most popular, but because it is a perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences. Chicken Tikka is an Indian dish. The Masala sauce was added to satisfy the desire of British people to have their meat served in gravy.”

More recently, former British Prime Minister Theresa May said that Chicken Tikka Masala was on par with Fish & Chips as a national UK dish.

Third, let’s talk about the history of how Indian food became popular enough to reach “national dish” status (and why Dishoom is well-placed to carry the mantle moving forward).

The popularization of Indian food in the UK is closely linked to the rise of curry houses. These restaurants — typically operated by Indians, Pakistanis or Bangladeshis — date all the way back to the early-1800s but really took off in the 1960s.

How? We need to set the table (pun very intended) with some quick political background.

In 1948, the UK parliament passed the British Nationality Act, which allowed migrants from across the Commonwealth to live and work in the UK with few restrictions. Soon, many citizens from newly-independent India and Pakistan came to the UK to fill labor shortages. Between 1962 and 1971, the UK passed three Acts that progressively added more restrictions on Commonwealth immigration. The Immigration Act of 1971 vastly altered Commonwealth immigration by establishing different classes of British subjects.

A wave of South Asians entered the country before the most restrictive rules set in and Bangladeshi migrants kicked off the curry house movement.

They did so by adapting South Asian flavours to Western palates.

In a 2017 article, The Guardian explains the trend by tracing the history of one curry house proprietor:

[Oli Khan’s] father, who arrived in Britain from Bangladesh as a waiter in 1962, had taught him that there was good money to be made in selling curry to the British, if you could adapt it to their taste for predictable sauces on a sliding scale of heat (mild korma, medium Madras, fiery vindaloo). For thousands of Bangladeshi immigrants in the 60s and 70s, working in Britain as OCs (“onion cutters”) and DCs (“dish cleaners”) was a way out of an even more precarious existence back home.

Adapting South Asian dishes to British tastes is what led to the creation of Chicken Tikka Masala. This delicious invention is often credited to Pakistani chef Ali Ahmed Aslam, who worked in Glasgow during the 1970s. As the origin story goes, Aslam was asked by a customer for more gravy, so he obliged by adding creamy tomato sauce to chicken tikka (boneless baked chicken skewers).

Now, it’s important to flag that many South Asians living in the UK derided the Bangladeshi curry houses and Chicken Tikka Masala. The less spice-filled dishes were seen as selling the F out. THIS WASN’T REAL SOUTH ASIAN FOOD!!

But that is the beauty of fusion (eg. it’s a minor miracle that Vietnamese immigrants were able to make Fish Sauce a thing in North America).

Despite the naysayers, the curry houses were a massive hit in the UK for the remainder of the century:

When the first significant wave of south Asian people settled in British towns in the 1960s, sometimes their neighbours complained that their cooking “stank”. Some white residents in Birmingham even went so far as to demand rate reductions from the city council to compensate them for the smell of spice. But slowly almost everyone was won over by the flavours. For those who really couldn’t stomach spice, there was usually an “English” section of the menu, offering an omelette and chips.

In the 1970s and 80s, more chefs arrived from Bangladesh. This was the golden era of the curry house, when its only real rival was long-life Vesta curry, that peculiar amalgam of dehydrated mince in brown sauce. By 1980 there were roughly 3,000 curry houses. During the following decade, Manchester began to promote the largely Pakistani restaurants of its famous Curry Mile as part of a trade renaissance. One of the reasons to visit Birmingham was now the balti curry, invented by immigrants from Pakistan — a one-pot dish made with cumin, cloves and cassia bark, served with extra-large naan breads. Britain’s appetite for curry now looked as enduring as our love of tea and toast.

Curry houses boomed like my bathroom the last time I went to an all-you-can-eat curry buffet. The number of these restaurants in the UK went from less than 500 in the 1960s to 6,660 by 1990 and peaked around 12,000 in 2010 (the Sylhet region of Bangladesh accounted for ~80% of Britain’s curry chefs).

Let’s zoom in from the macro to the micro with some food p0rn details on how the Curry houses prepped:

Each day, the chefs cooked up a gigantic vat of “base sauce” which could be adjusted to varying degrees of hotness and creaminess to suit the diners’ tastes. This sauce consisted of onions and carrots simmered with ginger, garlic, turmeric and other spices into an all-purpose orangey gravy. A dollop of this base sauce was sizzled in a pan of ghee, cooked meat and vegetables. If red peppers and green chillis were added, it became a jalfrezi. With yoghurt, garam masala and almonds, the same sauce transformed into a pasanda.

I can smell that last paragraph and it’s god damn delicious.

By the 2010s, South Asian cuisine was such a staple of UK life that Wetherspoon — one of the largest pub chains — became the country’s largest seller of curry thanks in large part to its “£6 Thursday curry nights” (curry had long been a go-to source for post-boozing eats with punters dropping the line, “I’m going for an Indian”).

But if Wetherspoon was the largest slanger of curry in the UK, what did that mean for the curry houses?

A 2023 piece from The Guardian — which has been milking the curry house beat — says curry houses have declined from a peak of 12,000 locations down to 8,000 locations and provides a few reasons:

Children of Proprietors: As with most immigrant parents, they hustled hard so their children could do different (and more aspirational) jobs. Making a gigantic vat of base sauce was less appealing for a new generation of South Asians vs. careers in engineering, consulting, computer programming and literally anything other than making a gigantic vat of base sauce. This same phenomenon happened with the Irani cafés, too…which is also why it’s so wild the Thakrar cousins decided to open a restaurant.

Changing Tastes: Curry houses and Chicken Tikka Masala expanded the UK’s taste profile. But then that taste profile expanded to Korean, Thai, Vietnamese, Mexican and [insert country] cuisine that have exploded in popularity in recent decades. Also, Curry houses no longer have a monopoly on Curry house flavours. We talked about Wetherspoon earlier, but there’s also a bounty of packaged grocery store curries and make-at-home curry kits.

Brexit/Immigration: With fewer British citizens wanting to work in Curry houses, these restaurants needed migrants to staff up. But a trend towards tighter immigration is a blocker. In a glorious hail Mary, the David Cameron government in 2012 set up 5 curry colleges in “Birmingham, Manchester, London and Leeds, funded by £1.75m in public money, to mitigate the harsh effects of the coalition’s immigration policy on curry kitchens” per The Guardian. Unfortunately, these efforts mostly failed.

Within the last few years, post-COVID inflation has crushed the already thin margins for the mom & pop restaurant industry (The Guardian projects the number of curry houses to decline by another 50% to 4,000 locations in a few years).

The loss of curry houses is no small lentil beans.

In the decade to Brexit in 2016, it is estimated that “Britain’s curry houses employed 100,000 people and generated annual sales of £4.2 billion.”

Here’s some napkin math: the above sales figures show that curry houses were doing an average of £420m a year during its near peak-period of 2006-2016.

In 2024, Dishoom did £137m (or 1/3rd of those sales) with just 10 restaurants (the Glasgow location opened in 2025).

In other words, Dishoom has really become the standard bearer for South Asian food in the UK and it did so by offering a mid-tier option:

At the low-end of South Asian food offerings were the curry houses (then grocery stores, Wetherspoon etc).

At the high-end are Michelin-starred Indian restaurants. A few notable names include Gymkhana, Opheem, Amaya, Benares and Veeraswamy.

Dishoom slotted in the middle. Its dishes (a combination of Indian, Iranian, colonial Bombay) are more authentic and varied than the low-end while being much more affordable and accessible than Michelin options.

Dishoom also has a large restaurant footprint. Curry houses typically have seating for <50 patrons. The first Dishoom at Covent Garden had 322 indoor seats and the chain has an average of 255 seats across its 11 restaurants.

Clearly, the Thakrar cousins used that counter-positioning curriculum from Harvard’s MBA program and perfectly slotted Dishoom against the competition. Then, they followed it up with a number of smart culinary, operational and marketing decisions as we’ll discuss in the next section.

***

The Dishoom Playbook

There are two benefits of going to Harvard Business School.

First, you’re halfway through learning the sum total of human knowledge:

Second, if you’re future venture pops off, there’s a very high likelihood you will score one of those sought after Harvard Business School case studies.

And Dishoom has popped off because the Thakrar cousins are absolutely cooking right now…literally and figuratively (and we know this because private companies in the UK have to file financials that are publicly available).

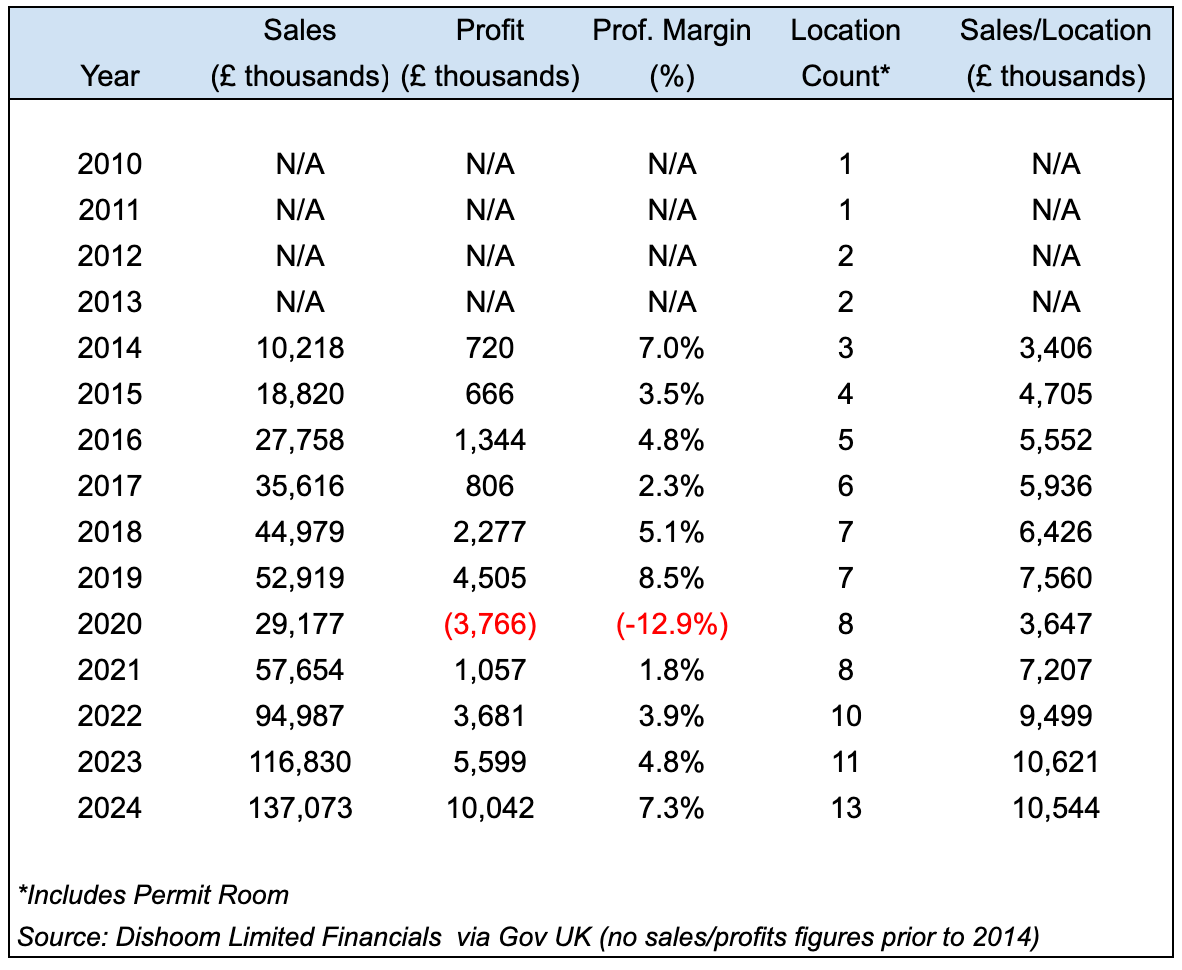

Between 2014 and 2024, Dishoom sales grew 13x from £10m to £137m. Understandably, the chain’s profitability took a hit during COVID but its profit margin has climbed back to 7.3% even as it expanded rapidly (including the addition of a bar-cafe concept called Permit Room):

Dishoom (11 locations): Covent Garden (2010), Shoreditch (2012), King’s Cross (2014), Carnaby (2015), Edinburgh (2016), Kensington (2017), Manchester (2018), Birmingham (2020), Canary Wharf (2022), Battersea (2023), Glasgow (2025)

Permit Room (4 locations): Brighton (2023), Oxford (2024), Cambridge (2024), Portobello (2025).

Over the past decade, the average revenue per location n has also grown from an average of £3.4m to £10.5m. To be sure, the total revenue number in recent years is a bit inflated by the fact that Dishoom started operating dark kitchens during COVID.

Either way, the chain is maximizing its real estate and clearly growing. That’s what happens when all the learnings, kitchen reps and consumer mindshare compounds.

And, sure enough, Harvard Business School rewarded Shamil Thakrar with a case study. In August 2024, professors Anjali Bhatt and Thomas DeLong published a piece on the chain that mirrors the name of its cookbook: “Dishoom: From Bombay with Love”.

Someone from the HBS faculty will probably slash my tires for sharing these insights but here is some of Dishoom’s playbook from the case study:

Open All-Day: Curry houses are most popular for dinner and/or after 5 pints of Guinness. Conversely, Dishoom serves breakfast (chai is popular) and the line up that forms from the morning creates FOMO at lunch, which attracts even more patrons. Then, the dinner keeps the party going until midnight (Dishoom’s CEO Brian Trollip tells HBS that “in late 2011, Shamil and I were pounding pavement handing out free breakfast coupons in the door…we gave away more breakfast than we charged for in the first two years of running Dishoom…now I think we might have the busiest restaurant [for breakfast] in the country.”)

A Diverse Menu: Dishoom offers a variety of tastes that appeals to many different palates (Per HBS, “Several of Dishoom’s offerings were quintessential to Irani cafés, such as akuri, a spiced version of scrambled eggs, and bun maska, described by Dishoom’s menu as a ‘soft bun with butter inside.’ Other regional dishes included prawn koliwada, which originated from the indigenous fishing population of Bombay, and pau bhaji, a popular Bombay street food based on Portuguese bread rolls. Many items were recognizably pan-Indian but incorporated a Bombay variation, such as samosas made with filo instead of shortcrust. Lastly, a few breakfast items, such as the signature bacon naan roll, unmistakably catered to a British palate.”

Consistent Tastes: A key for the menu selection is that each dish can be scaled without losing quality (Dishoom’s current Executive Chef Arun Kumar says, “We tell our chefs: we are not executing complicated fine dining dishes. What we are doing is ensuring consistency by following our recipes meticulously, down to the gram. When we consider a menu change, our primary question is whether we can maintain the quality and consistency of a new dish for 100,000 guests who come through our doors every week. I think this obsession with quality and consistency is what keeps us alive.”)

Each of the 11 Dishoom restaurants has a different interior and “the guest journey [is] orchestrated down to the minute.” While waiting in (the often long) lines, people in the back will get a chai and employees will constantly check in. The layouts create energy while patrons, hosts and cooks bounce around the tables

The Dishoom vibes weren’t always so vibey. Shamil says that the first few locations were much too focussed margins and bean-counting. It’s hard to shake that MBA consulting brain, but he eventually did and realized that the long-term potential is highest when the main focus is quality and experience.

Meanwhile, Dishoom is ranked highly as an employer, often cited as the top hospitality workplace in the UK. The chain now employs ~2,000 people and looks to promote internally (employees that stay 5 years also do a Bombay Bootcamp excursion in India to learn more of the company’s background).

All of these elements hit the spot on my visit to Dishoom.

The most memorable part of my meal in Glasgow was definitely the energy, the Okra Fries and my attempt at trying to roll a 6 on the dice to get a free meal.

This 16.67% expected value dice game discount was inspired by Matka, the Hindi word for “pot” that also refers to “the illegal underground lottery that sprang up in Bombay in 1962.”

There’s just something about the gambling aspect that takes an objectively meh discount to the next level.

“Do you smell that?” I asked my wife when we were seated.

“Jasmine? Tandoor?” she guessed.

“No, it’s the smell of a free meal,” I told her before making an unnecessarily large order on the expectation that I wasn’t going to have to pay for it (and that’s why universal healthcare systems have the concept of rationing).

Ogilvy’s Vice Chair and leading advertising exec Rory Sutherland relays a similar story about the appeal of Dishoom’s dice game:

There were these guys from Chicago [who didn’t know we worked with Dishoom].

They go, “Oh, you’re from London? Every time we got to London, we have to go to Dishoom. We go before 6 o’clock…and we bring a guy along from London who we think has a hot hand.”

What was weird…is that half [these people] could have bought the f**king restaurant.

These people wouldn’t have crossed the road for a 16.67% discount. I don’t know why [other restaurants] haven’t nicked this. Because one of the advantages is that if there is a 1 in 6 chance of getting a meal for free, you spend more.

Because you’d feel a bit of a dick if you skimped on everything then [you] ended up winning your meal.

Unfortunately for me, there is a notable caveat with Matka: you had to have eaten at least once at Dishoom before (after that first meal, they give you a keychain charm that you can show them before rolling the dice on a future visit).

Damnit. This is understandable, since you want to incentivize loyalty and don’t want one-time tourists just throwing dice around. But, damnit.

Still, I was happy to pay full price for the meal and they let me roll for fun anyway. I got a “1” like a total loser. To add insult to injury, here I am writing about it and giving them free word-of-mouth (there are countless clips of people at Dishoom playing Matka on socials).

But now I know the rules. So will many more people in North America once the Dishoom New York expansion kicks off in 2026.

Which leads us to the billion-dollar question: can Dishoom keep scaling without destroying the soul of the business?

If the chain had to take an investment, the LVMH-linked L Catterton is definitely an ideal partner.

LVMH is among the handful of go-to firms in the world for bringing luxury experiences to the masses. It does so by carefully managing brand by limiting supply and creating demand.

However, this is a very difficult balancing act.

A recent L Catterton case study is instructive: Birkenstock.

Between 2012 and 2022, sales for the iconic sandal brand grew 5x from ~$250m to $1.3B. Amidst the sales boom, L Catterton bought Birkenstock for $5B from its founding family in 2021 with an eye to grow the brand even more.

Birkenstock went public in October 2023 at an $8.6B valuation. Sales in 2025 are expected at $2.5B while the market value has slipped to $7.3B.

Has Birkenstock saturated its addressable market? Is it at risk of losing its appeal because it’s too available?

Obviously, an Indian restaurant chain is different than a 250-year old brand inspired by footwear worn in the Bible.

Dishoom seems a long way from being saturated, though. It still has many more regions of the world to conquer and the fact that it is an IRL experience is a tailwind as people get sick of being on their smartphone 10 hours a day.

In fact, L Catterton made another high-end dining experience bet a few days prior to its Dishoom investment by acquiring Kisshokichi, the world’s largest Kobe beef restaurant chain.

These guys are not dummies and the Dishoom/Kisshokichi combo of deals seems to be a bullish signal for the future of the accessible fine dining industry. More broadly, it’s a bet on IRL. The same bet that Ari Emanuel — the CEO of TKO Group (UFC/WWE) and owner of other live events (tennis tournaments, Frieze art fairs, car auctions) — is calling “Anti-AI” bet, the thesis that AI-powered productivity will lead to more human free time and higher demand for social experiences.

For Dishoom, a notable restaurant comp might be Din Tai Fung. Founded as a cooking oil business in 1958, it rebranded as a noodle shop in 2000 and has expanded to 180 locations in 13 countries. Known for its soup dumplings, Din Tai Fung has brought higher-end Taiwanese-Chinese cuisine to the world. Annual sales have reached $440m and Din Tai Fung has the highest average unit volume per restaurant in America ($27m per restaurant across 17 locations).

For his part, Shamil Thakrar’s motto on building the Dishoom brand is “deepen, don’t dilute”.

Stick to that philosophy — while continuing to convince Vietnamese-Canadian travellers in Glasgow that a 16.67% expected value discount is the greatest deal ever — and Dishoom’s restaurant journey may just be getting started.

This issue of SatPost is brought to you by Bearly AI

Are you looking for a no-logging, encrypted and anonymized AI chat tool?

Then try the Bearly AI research app, which provides an easy-to-use UX for the newest models from OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, DeepSeek, Gemini and more.

While some AI providers keep chat logs indefinitely even after a user deletes them...Bearly AI has a default no-logging policy and user chats are encrypted while requests to LLM providers are completely anonymized.

Try one month FREE of the Pro Plan using the code BEARLY1.

The wild economics of smoking

Around the late-2000s, one of the most jarring business and social changes I remember was the disappearance of cigarettes from bars, clubs and restaurants.

It’s so crazy that people used to go out at night, step into a bar or restaurant and instantly smell like an ashtray. Just all over our clothes in our hair. We probably didn’t realize it because everyone smelt like an ashtray.

Then inside smoking was banned and we all moved on, requiring 2-3 fewer showers per day.

This jarring change was a whiplash for me, though.

Because just as cigarettes disappeared from public spaces in North America, I moved to Vietnam.

Today, about 80% of the world’s cigarette smokers live in low or middle-income countries. Those devious tobacco execs had aggressively marketed to young and female smokers in developing markets to make up for lost smokers in the West.

They lobbied like crazy, kept prices low, made flavours for local markets and did packaging “innovation” (selling individual smokes).

I saw it everywhere while living in Southeast Asia for 5 years.

Since then, my mental model of tobacco companies has been that they are completely cooked in North America while thriving in the poorer regions.

Turns out I underestimated those wily tobacco execs.

The Economist has a fascinating article on how tobacco stocks have outperformed tech stock (NASDAQ in the recent years and it’s a textbook example of “price-inelastic” buyers:

Over the past decade, the # of US smokers has declined by 20m and the total # of cigarettes sold is down by a 1/3rd.

So, cigarette firms have charged more to their most committed smokers (operating margins have grown from 50% to 60%).

In 2025, cigarette makers in the US will make operating profit of $22B.

Certainly, some of that stock performance may be due to tobacco’s pivot to vapes and chewy pouches.

But cigarettes are still very much part of the story. While the industry goes away, only the most addicted smokers are left. And cigarette companies have been raising prices increasingly faster (with no impact on demand).

In 2017, a pack of Marlboros went up 2.9% YoY (vs. inflation of 2.1%). In 2024, they raised the price of Marlboros by 7% (vs. inflation of 3%).

Imperial Brands said on an earnings call, “[W]e can continue to take pricing to offset volume declines” (while British American Tobacco recently stated its “price/mix more than offset volume decline.”)

Winston Churchill Loved Stonks

While we’re on the topic of the British Empire (Dishoom) and stock markets (smokes), we need to talk about how much Winston Churchill loved YOLO-ing equities.

Andrew Ross Sorkin has a new book on the 1929 stock market crash (“1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History--and How It Shattered a Nation”), which is obviously super timely because the current AI wave is looking a bit…ugh…bubbly.

Anyway, there are some incredible tidbit on Churchill aka The British Bulldog being extra bullish on American stocks right before The Great Depression:

Churchill no longer had the kind of money his parents did; he did not inherit significant sums and he wasn’t an heir to the family estate at Blenheim Palace, which belonged to his cousin. Desperate to achieve the wealth of those around him, he quickly opened a new trading account, intent on reserving his funds, valued at about £20,000, for speculation. “This ‘mass of manoeuvre’ is of the utmost importance,” he told his wife, “and must not be frittered away.” […]

Churchill’s mind remained on money. He was fascinated with the American way of investing. He gave his new friend at E. F. Hutton control over his share account while he was traveling. “His firm has the best information about the American market,” he told his wife. “All this looks very confiding—but I am sure it will prove wise.” […]

Inspired by such tales and the confidence “Barney” had in the current market, Churchill began to play the market even more heavily. His account had a trading volume in stocks—buying and selling—of more than £400,000 in a week, much of it on margin. […]

Two of the most popular comments when I posted this on X was “incredible, he’s a degen” and “one of us, one of us”.

Churchill was in New York on Black Monday and despite seeing the madness, had this to say, “No one could doubt that this financial disaster, huge as it is, cruel as it is to thousands, is only a passing episode in the march of a valiant and serviceable people who by fierce experiment are hewing new paths for man, and showing to all nations much that they should attempt and much that they should avoid.”

It took Churchill a long time to financially recover from this L:

Through the 1930s, he remained functionally broke, barely staying ahead of creditors by taking writing fees to publish a torrent of articles, including one about being hit by the car in Manhattan. After a long-overdue bill from his shirtmaker threatened to push him into personal bankruptcy, an Austrian-born financier named Sir Henry Strakosch bailed him out. When Churchill became prime minister, he finally had an expense account to match his appetites. A massive book deal for his World War II memoir, as well as relatively lavish sums for film rights to previous books, gave him the financial security he had lacked for most of his life, and when he died in 1965, he had money to leave his heirs.

Links and Memes

Red Bull’s Mt. Everest Stunt May Have Been Its Most Dangerous: Energy-crack-drink-gasoline-tasting-beverage firm Red Bull is legendary for its marketing stunts.

A related stat: Red Bull spends 35% of sales on marketing, which is significantly more than Coca-Cola or Pepsi (<10% of sales).

Anyway, Red Bull went wild for its latest marketing play. Polish ski mountaineer Andrzej Bargiel climbed Mt. Everest and then ski’d down…and did it all without supplemental oxygen. Going sans bottled oxygen was a world’s first and — let’s be honest — none of us even knew “ski mountaineer” was a job.

This was particularly dangerous because Bargiel spent 16 hours in the “Death Zone”, which is incredibly ominous. And it’s so named because that describes a part of Everest that is above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) of altitude where oxygen levels are 33% of normal and insufficient to sustain human life for more than 18-20 hours.

The 31-minute YouTube video has some insane visuals and a spot-on top comment: “this is somehow simultaneously one of the most peaceful and terrifying videos I’ve ever seen”

Hilariously, Bargiel had to chug a Red Bull after completing the stunt, which is probably the last thing in the world you need to do after spending 16 hours in the “Death Zone” but, hey, the bill isn’t going to pay itself.

***

Some other links for your weekend consumption:

New Toy Story 5 trailer dropped…and the villain looks like an iPad. This is obviously ironic since Steve Jobs yelled at enough people to make both Pixar and the iPad become successes. It’s an interesting idea but I’m with Quentin Tarantino, who says that the first three Toy Story films were the perfect trilogy and there is no creative reason to make more.

“Bring the big leagues to Mexico City”…Nate Silver makes the case for the NBA, MLB, NFL or NHL to bring a team to Mexico City (which is the largest North American market without a Big 4 sports team).

Nothing in the world can prepare you for how Boris Johnson…pronounces the words “AI” and “ChatGPT”.

The step-by-step Dream Sheet that Shohei Ohtani…created in high school to help achieve his baseball goals.

The CEO of Walmart Doug McMillon is retiring at 59…he grew up in Bentonville, Arkansas and went to the University of Arkansas. His first job at Walmart was as an hourly summer associate in 1984 and then took the top job in 2014. In the past decade, Walmart stock is up more than 3x and McMillon built an e-commerce beast second only after Amazon.

Berkshire Hathaway invested $4.3B into Alphabet…which makes it the 10th largest position for the stock conglomerate. This was probably one of Buffett’s final greenlights on the investing front. Berkshire famously shunned tech before smashing it out the park with its Apple investment in 2016. But, interestingly, Munger and Buffett have regretted missing Google’s IPO. They actually had insight on the company because GEICO was buying so many insurance search ads and they knew how effective it was. Full circle.

Google also released its new Gemini 3 model this week…and it’s very impressive. The model has been used to “one shot 3D LEGO editors” and create full games from a text prompt. Professor Ethan Mollick has a great breakdown on the very very impressive Gemini 3.

Big Daddy Bezos is BACK…in his first official operating role since leaving the Amazon CEO job in 2021. He is now co-CEO of Prometheus Projects, an AI startup that has poached dozens of employees from OpenAI and DeepMind and has raised $6.2B (mostly from money in Bezos couch cushions). The startup is part of the “physical AI” wave and will use AI to discover new engineering and manufacturing techniques for computers, cars, and spacecraft.

Famed short-seller Michael Burry…has made notable bets against major AI plays including Nvidia and Palantir. He also recently de-registered his hedge fund and looks to ride these bets out on his own (without investor money). QTR Fringe Finance has a solid breakdown of the play and what it says about the market.

Microsoft Satya Nadella CEO…replied to a Bearly AI post about Microsoft Excel with maybe the greatest hoodie ever seen in Corporate America.

…and them wild posts:

Finally, the absolute wildest meme of the week was definitely billionaire hedge fund manager Bill Ackman sharing dating advice on X and included the idea to approach a potential romantic partner by asking “May I meet you?” and the post went nuclear with 35m views.

Now, before making any knee-jerk jokes, I want to say that I think he’s coming from the right place. Ackman frames his advice around the idea that “many young men…find it difficult to meet young women in a public setting” and “online culture has destroyed the ability to spontaneously meet strangers.

I got into a long-term relationship before Tinder and Instagram. Based on everything I’ve heard from my single friends, that sounds like a huge blessing. Sounds like past decade of online dating has scarred people.

But obviously, the internet went full cynical by noting that Ackman is a billionaire and could literally say anything to close the deal. His advice was for pre-billionaire and single days, though. But then people noted he’s 6’3 and a good-looking dude (his current wife was reported to be seeing Brad Pitt when Ackman started courting her).

While “May I meet you?” has some serious 1920s energy and is massively dorky, it’s not the worst thing ever. It was just so out of left field. The hit rate on this opener is probably under 0.8% but...as...Wayne Gretzky...Michael Scott said...”you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take”. That’s the real point here and, also, the whole thing popped off because of how awkward “May I meet you?” sounds. Net-net, there will be at least one more baby conceived because of this post.

The Know Your Meme page has a solid blow-by-blow and ny favourite observation was from Lulu Cheng Meservey:

Unironically, “May I meet you” has just become a killer pickup line for this exact demographic: 1) gets a laugh; 2) inside joke creates shared connection; and 3) signals interest with low pressure.

But the only reason I’m telling you any of this is because the memes were absolutely out of control including a YOLO DM to Sydney Sweeney and people from both sexes trying the pick-up line….and these absolute gems:

Great post! Dishoom was a highlight of my work trip to London. Super vibey spot in Shoreditch and I was impressed by the customer service (chai in line, drinks while waiting for table).

Hi Trung, this is the second SatPost in a row I didn’t receive via email. I can’t seem to see a way of subscribing again so I’m not sure if I’ve fallen off or if something else has happened - not sure if you’re seeing any drop in your email views but I’m certainly not getting any more!

Still loving the work though, will just have to manually check sporadically.

All the best,

Tim