Hello Kitty's $80B+ Secret Sauce

Simple design + riding cultural wave + licensing machine = blockbuster character.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we’re talking about Hello Kitty and the secret sauce behind its multi-billion dollar empire.

Also this week:

Super Mario Bros. $380m opening

The business of Coachella

And them fire memes (including $11 sandwiches)

One Wikipedia entry that recently blew me away was “Highest-Grossing Media Franchises”. As of September 2022, these were the top 10 franchises by lifetime sales (including film, TV, games, merchandise, DVD, and print etc).

Pokémon ($119B)

Hello Kitty ($89B)

Mickey Mouse ($83B)

Winnie The Pooh ($81B)

Star Wars ($69B, nice)

Super Mario ($48B)

Disney Princesses ($46B)

Anpanman ($45B)

Marvel Cinematic Universe ($38B)

Harry Potter ($33B)

The reason I am referencing “September 2022” is because the current Wikipedia list has adjusted its figures and put Hello Kitty’s lifetime sales at $19B (vs. $89B). I think the lower number is incorrect (and some Wikipedia moderators agree if you go through the page edits).

Here is what we know: Hello Kitty has been around since 1974 and, as recently as 2013, was selling $8 billion worth of merchandise annually (it sold another $5 billion in 2014). It is very reasonable to believe that Hello Kitty merchandise — which covers a range of 50,000+ items (sold in 15,000+ shops globally) — has made $89B in lifetime sales, which is roughly equal to the combined all-time sales for Batman, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) and James Bond IP.

Hello Kitty wasn’t very popular when I grew up in Canada. But I spent 5 years in Southeast Asia (mainly Vietnam) after University and the cute cat-looking character was everywhere.

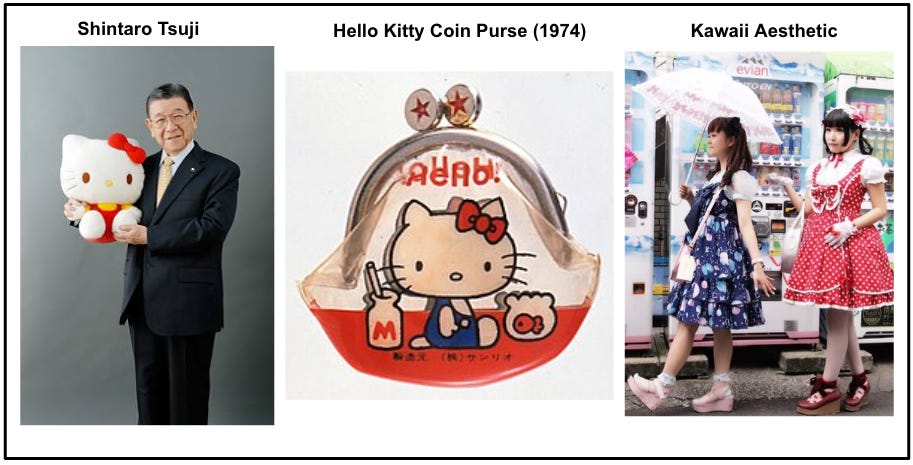

The company behind Hello Kitty is a Japanese firm called Sanrio, which has a very interesting story. Its founder Shintaro Tsuji was obsessed with Walt Disney. And he built a merchandise and licensing machine in an attempt to match the global influence of his idol.

We’ll cover the story by looking at:

The start of Sanrio

Hello Kitty’s design secret

Expansion and reinvention

The start of Sanrio

First, a big shoutout to Christine Yano, an anthropology professor at the University of Hawaii. Much of this article is informed by her 2013 book Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty's Trek Across the Pacific.

My biggest takeaway from the book is that Hello Kitty is so much more than a business phenomenon. Its success is tied to culture, geopolitics and sociology, which is why Yano’s anthropological perspective is so valuable.

Let’s start the story in 1960. A 32-year old Shintaro Tsuji quit a safe bureaucratic government job to launch a dry goods manufacturer called Yamanashi Silk Center. At the time, Japan was still recovering from the devastation of World War II and global consumers saw Japanese goods as low quality. Japan’s image as a technological innovator was still decades away (side note: Toto’s heated bidet toilet seat is the greatest invention ever).

In 1973, Tsuji changed his business. Why? In order to capitalize on two trends: 1) globalization; and 2) “fanshii guzzu”, which was a commercial craze of young Japanese girls purchasing stationary, greeting cards, small items and accessories (such as purses and key chains).

As Yano explains, Tsuji changed his company’s name to capitalize on the first trend:

[Tsuji] devised “Sanrio” from a combination of San (as in many names of West Coast cities in the United States, such as San Francisco and San Diego) and Rio (Spanish for river). The resulting name referenced not so much Spain or any Latin American country, as California, home of his hero and idol Walt Disney.

To capitalize on “fanshii guzzu”, Tsuji implemented a lesson he had learned while selling rubber sandals at the beach in the 60s. The Japanese entrepreneur had conducted an old school A/B test: he put a flower design on sandals and noticed that they sold much better than those without a design.

"If you attach added value or design to the product,” Tsuji said, “They sell in a completely different way." To keep “adding value” to his product line, Tsuji created an in-house design team (and dabbled in licensing by buying the Japanese rights for Western characters like Snoopy from the Peanuts comics).

Hello Kitty entered the picture in 1974. Sanrio designer Yuko Shimizu dreamed up a cat-like character that would become Sanrio’s answer to Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse (one of Tsuji’s main inspirations). Her image was first placed on a coin purse. Unlike Disney characters, Hello Kitty has little backstory or lore. Instead, the design appealed to young females as an icon of “kawaii”, which is the Japanese culture of cuteness.

Either way, it blew up. Tsuji seized on the popularity to fulfill his ambition to sell outside of Japan. To prevent copycats, he made a strategic decision that laid the groundwork for a licensing empire: “To prevent imitators our principle was to get copyrights,” Tsuji told the Financial Times in 2010. “A patent lasted for 15 years [now 20 years] but copyright lasted for 50.”

As part of an expansion to the United States in 1976, Hello Kitty was given a thin origin story as an English teenage girl. Yes, a girl and not a cat. This strategy makes sense when you remember that the UK dominated pop culture in the late 1960s and early 1970s (as John Lennon said, “The Beatles are more popular than Jesus”).

But I’m burying the lede here. Hello Kitty’s multi-decade dominance has nothing to do with the character’s backstory.

Hello Kitty’s design secret

Many credit the success of Hello Kitty to its simplistic design: a round face, with two triangular ears, a circular nose, whiskers and a ribbon. Notably, there is no mouth and, consequently, not a ton of emotion.

Tsuji says the design is very intentional. The ribbon is meant to “join people together” in friendship. And “no mouth” is meant to demonstrate that Hello Kitty can only help someone and show friendship by guiding them with her hand (critics of “no mouth” say it is a form of muffling female speech and empowerment).

Regardless of the rationale, the silhouette is both instantly recognizable and also a blank canvas for anyone to project their feelings and art onto. Hello Kitty’s malleability makes it an image that can — and has been used — by all types of culture and people.

Remember, Tsuji idolized Disney. The Japanese entrepreneur clearly learned lessons from the aesthetic evolution of Mickey Mouse. If we are being honest with ourselves, the OG Mickey Mouse from the 1920s is one ugly dude. In the following decades, Disney gave Mickey Mouse a much cleaner silhouette. One that is now instantly recognizable. And “instantly recognizable” is a boon for licensing businesses.

In addition to a meme-able design, Tsuji leveraged two Japanese qualities that propelled Hello Kitty:

Gifting culture: The “fanshii guzzu” craze of young Japanese girls purchasing inexpensive accessories. This was turbocharged by the fact that the Japanese frequently exchange gifts as a sign of friendship and appreciation (I also find gifts of DoorDash credits a sign of appreciation). Hello Kitty’s founding motto was “small gift, big smile”, and the low prices meant these gifts were swapped often and became ubiquitous.

Kawaii (cute overload): You know how there is a hipster aesthetic? Such as flannel shirts, beards and sweet-looking beanies? Well, use that frame of thinking for the kawaii aesthetic. It is a female look of wearing bows, animal backpacks, bright pink colors and elaborate animation-themed outfits. The look is not just for young girls, either; as Yano explains, the “fetishization of schoolgirls in Japan” and Lolita complex means that “sexy is not such a far reach from kawaii in contemporary Japan” (aka the kawaii aesthetic is frequently adopted by adults). What does Hello Kitty have to do with this? The character is one of the most famous representations of kawaii.

By combining these elements — design, gift culture and kawaii — Hello Kitty has been able to thrive globally and over time.

Expansion & Reinvention

By the late 1960s, Japan had already become the second largest country for imports into the US. A major reason for this was America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. The US was shipping weapons and equipment containers to Southeast Asia and — instead of sending empty containers back across the Pacific — it began to fill the returning ships with Asian export goods.

Japan took advantage of this logistics decision. And after America left Vietnam in 1975, the reputation of Japanese exports to move from low-value manufacturing (e.g. apparel) to high-tech expertise (e.g. cars like Toyota, electronics like Sony Walkman). This multi-decade change created an economic giant.

Japan’s economic rise created ripe conditions for Hello Kitty — a cultural phenomenon that cut across age and income groups — to take hold of the national mindshare.

“The bubble allowed middle-class practices to become more than the norm,” Yano writes in Pink Globalization. “they came to represent an assumption and hallmark of national achievement as ‘homogeneous Japan’. [Although] this was far from the truth, the rise of Japanese cute culture, including Hello Kitty, should be seen within the discursive assumptions of a shared middle class and its unspoken aspirations.”

Sanrio’s Hello Kitty licensing business went global during this period with low-priced accessories finding their way into shops across Europe, America and East Asia.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing, though. Hello Kitty’s initial success in the late-1970s didn’t even last through the 1980s. Why? Because a Japanese manga character called Doraemon took the popularity crown (I used to have a Doraemon watch and it slapped).

According to a case study by Marketing Mastermind, Hello Kitty saw a revival in the 1990s. Recall that the Hello Kitty kawaii aesthetic appealed to customers of all age groups. Young girls in the 70s who bought the Hello Kitty coin purse entered the workforce and put Hello Kitty clocks on their desks in the 90s. Or, as a bridge to the next generation, these same fans bought Hello Kitty trinkets for their children. Sanrio also opened two theme parks early in the decade: Puroland (1990) and Harmonyland (1991) outside of Tokyo, which now attract 1.5m+ people a year.

Meanwhile, Hello Kitty’s international reputation gained despite the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble (at its bubbliest, the real estate under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth more than all the real estate in California).

How did Japan maintain its cultural status despite an imploding economy? Since its establishment in 1980, the country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs had been running an international campaign called Cool Japan, which promoted soft power through “everything from games, manga, anime, and other forms of content, fashion, commercial products, Japanese cuisine, and traditional culture to robots, eco-friendly technologies, and other high-tech industrial products.”

This wasn’t the first time that modern Japan had tried to export culture at scale. The Japanese animation industry — with financial backing from the Imperial Japanese government — had developed film technology during World War II to create propaganda movies. The legacy of this close partnership is why there are so many famous Japanese animation studios (Toei Animation, Studio Ghibli, A-1 Pictures etc.) and why the niche anime streaming service Crunchyroll has over 15 million subscribers and a $1B+ valuation.

Back to Hello Kitty, the brand soon became “cool” in America and was further bolstered by celebrity endorsements. Hello Kitty’s licensing business capitalized on this perception to become a fashion symbol among celebrities including — brace yourself for some 90s pop music nostalgia — Christina Aguilera, Cameron Diaz, Mandy Moore, Paris Hilton and Mariah Carey (who famously had a Hello Kitty bathroom in her house).

At the turn of the century, Sanrio really went mainstream by collaborating with McDonald’s and Target. It then partnered with Swarovski to create a line of Hello Kitty jewellery. Additionally, there was a Hello Kitty-designed jetliner for Taiwanese carrier Eva Air.

To be sure, there were limits to Sanrio’s licensing ambitions. The ever-malleable silhouette couldn’t be used in sin industries (which is unfortunate, as a Hello Kitty Tequila would slap). A more recent challenge for Sanrio is that it has to keep finding new ways to make Hello Kitty relevant for licensees. In other words: we probably need another reinvention.

What’s Next?

Interestingly, Sanrio the company isn’t really printing money. It went public in 1980 and today has a market cap of $3.7B on annual revenue of ~$500m (keep in mind that it only captures a % royalty from the licensees). Unlike Disney, Sanrio’s theme park business regularly loses money. In the aforementioned interview with Financial Times, Tsuji said that running the park at a loss is fine because the operation provides jobs for his staff, which he prioritizes over partner manufacturers, customers, and shareholders.

In 2022, Japan contributed the majority of sales for Sanrio followed by South Korea. Then there’s a big drop off to Taiwan, China and Hong Kong with North America, Chile and the UK rounding out the rest of the major markets (of note: Sanrio dealt with Chinese counterfeiters by cutting a licensing deal with e-commerce platform Alibaba).

A read through of Sanrio’s last annual report shows the diversity of its licensees: such as Japan 7-Eleven lottery games, tomato ketchup, Pringles, Uniqlo pajamas, home appliances, accessories, puzzles and digital stickers for Line messaging app.

As a single character, Hello Kitty is truly an impressive achievement when you consider that the world’s top licensors — Disney, WarnerMedia, Pokemon, Hasbro, Mattel — have a stable of IP and have built fandom on top of a rich narrative tales.

Sanrio’s in-house design team has actually created over 400 characters including Cinnamoroll, Keroppi, Sugarbunnies, Maimaimaigoen and Bosanimal. But Hello Kitty is like Sanrio’s LeBron James and still shoulders the load. Coming up on 50 years, the $89 billion in lifetime merchandise sales for Hello Kitty sounds about right.

Looking ahead, the qualities that Yano highlighted as Hello Kitty’s secret sauce (generational bridge, kawaii) may be less dependable. Japan’s plummeting birth rate makes it difficult to “pass on” Hello Kitty to the next generation. And the appeal of kawaii — like any trend — will come and go.

Hello Kitty’s appeal among young North American girls has been dampened by the insane success of Disney’s 2013 film Frozen (I don’t want to exaggerate but every one of my friend’s daughters is obsessed with Elsa; like 97% hit rate). Back in Japan, the anime sensation Anpanman — which is #8 on the list that started this article — has been the country’s top earning character for much of the past two decades.

In 2020, the 93-year old Tsuji passed the reins onto the person who will have to figure out Hello Kitty’s next phase: his then 31-year old grandson Tomokuni. Early attempts to mix it up include some Metaverse and NFT projects (insert Michael Scott grimacing face).

Hello Kitty has so much existing mind share and brand equity that the Tomokuni-era still has time to hit a home run. While Sanrio has dabbled in TV and film in the past, there is certainly more juice to be squeezed. The recent success of an animated film based on another Japanese character with little backstory but a massive fan base —Super Mario Bros — points to a bullish scenario.

Until the next development, I am doing some research on this Wikipedia entry.

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email. If you press this blue button below, you can try AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

Links and Memes

Super Mario Bros blockbuster: The Nintendo film came out last week and smashed the box office with an opening weekend of $380m), marking a huge Hollywood comeback for the IP. Back in 1993, a live-action Super Mario Bros film bombed so badly that Nintendo refused to make a film for 3 decades. Per Deadline, the new version has been a success for a few reasons:

Nintendo teamed up with Illumination (animating powerhouse behind Minions)

Nintendo guru Shigeru Miyamoto was very involved with this film (unlike the 1990s, when Nintendo was experimental with its IP and gave up creative control to the studio)

The 2023 version was animated, sticking closer to the actual game vs. the 1993 version (which wanted to be a live-action blockbuster like Batman meets Blade Runner and had a not-so-great motto of “This is not a game”)

Rupert Murdoch and his children are widely believed to be the source material for the show Succession. This association really comes through in a lenghthy Vanity Fair profile of the Murdochs:

[Rupert] long wanted one of his three children from his second wife, Anna—Elisabeth, 54, Lachlan, 51, and James, 50—to take over the company one day. Murdoch believed a Darwinian struggle would produce the most capable heir. “He pitted his kids against each other their entire lives. It’s sad,” a person close to the family said. Elisabeth was by many accounts the sharpest, but she is a woman, and Murdoch subscribed to old-fashioned primogeniture.

That’s straight out of the HBO show, with Shiv far more capable than her three brothers. On a related note, Murdoch recently divorced model Jerry Hall and — as part of the split — she wasn’t allowed to speak to Succession show writers.

Steve Jobs Archive: A free — yes FREE — ebook collection of “Steve’s speeches, interviews and correspondence” from his time at Next, Pixar and Apple. It’s very good with lots of bite-size nuggets including Steve’s favorite quote via Aristotle (“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but habit”).

The Business of Coachella: Dan Runcie at Trapital has an amazing breakdown of Coachella. Some fun facts: 1) the first Coachella was in 1999 and tickets were only $50 (now it’s $500); 2) the famous Coachella poster gives a ballpark figure for how much artists are getting paid (headline names are paid $4-5 million then its $750,000 for the next row and then a big drop-off afterwards).

AutoGPT: The buzziest AI news this week is AutoGPT, which are autonomous agents that can execute detailed instructions and interact with other AutoGPTs. Nathan Lands has a good thread of applications including sales agents, product research, coding. My guess is AutoGPT can “write a weekly newsletter like a Vietnamese-Canadian guy named Trung” in about 3 weeks.

…and here some fresh tweets.

“Brand equity” is “the value of a brand, determined by the consumer's perception of its quality and desirability.” HBO has a lot of brand equity when it comes to creating award-winning prestige content. Last week, Warner Bros. Discovery decided to rebrand its streaming service HBO Max to Max (which will include Discovery+, HBO and a bunch of other crap that isn’t HBO).

What’s the rationale? Well, “HBO” is attached to edgy and grown-up content. Whereas “Max” is such a generic word that it can be an umbrella for anything, which is exactly what Max wants to sell (it sounds like there will be a lot of reality shows on the platform, and maybe some live news/sports). I initially thought the name change was idiotic but it may be a 10D chess move to protect the HBO brand and also make people forget that HBO Go/Now crashed during the Game of Thrones finale. In a guaranteed home run, Warner Bros did announce a 10-year long Harry Potter TV series.

And here’s the tweet of the week:

You misspelled the authors name as Yao throughout the article but her name is Yano.

The Sanrio name is derived from an alternative reading of 'Yamanashi' (prefecture, where Tsuji is from) which would be 'san + ri' and 'king' which is 'o.' Though the one mentioned here would definitely be easier for Western interpretation 😂

I enjoy reading Tsuji's monthly letter as the Strawberry King in the monthly Sanrio newspaper called the Strawberry Newspaper (it's in Japanese). Still going strong at 90+ years old! It's a lovely read every month. Don't think Sanrio operates like Disney which is very much a money machine - their mission seems to be more making customers happy with little things 😊