How Tech Metrics Change Your Values and Behaviour

Insights from philosopher C. Thi Nguyen's book "The Score".

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about philosopher C. Thi Nguyen’s new book “The Score” and how tech apps metrics are able to influence your values and behaviour.

Also this week:

Apple Finance Forays

Alcohol Makers Are In Trouble

…and them wild posts (including a new ChatGPT prompt)

You just woke up.

Oura Ring says your sleep score is 55 (“I guess I feel a bit groggy”).

Apple Watch says you need 13,579 steps to hit your weekly goal (“Will feel way better after hitting that number”).

Stock portfolio is down 3% (“Ugh, I’m an idiot. Need to stop buying quantum stocks based on random comments 84 replies down in a Reddit thread”).

X shows you gained 478 followers overnight and your last post had 10,901 likes (“People love my takes”).

Kalshi just paid out $17 for you correctly predicting it would snow more than 2 inches in Boston (“Man, I’m smart”).

Your NBA fantasy team just took the #1 spot in the league after Jokic dropped a 56-18-17 triple double (“MAN, I AM VERY SMART!")

Duolingo’s notification says you are on a 78-day streak of Spanish lessons…keep going (“HOMBRE, SOY MUY INTELIGENTE!”)

It’s only been 4 minutes and your central nervous system has been put through an emotional roller coaster, all triggered by a number (metric, ranking) from an external source (in this case, tech apps).

You’ll spend the rest of your day thinking about and making decisions based on these and other external metrics (sales quotas, word counts, tickets closed, billable hours, 5km run time, calorie targets, pull requests, amount of deep work, pages read, savings rate etc.).

Why do these metrics exist? Why do we design our lives around them?

Of course, they set goals and are easily trackable, thus helping us accomplish tasks deemed important in our lives.

But that is really just the tip of the iceberg.

In a new book titled “The Score: How to Stop Playing Somebody Else’s Game”, C. Thi Nguyen — a professor at the University of Utah who studies the philosophy of games — helps to answer these questions at a much deeper level.

One of his key insights is a concept called “value capture,” which explains how the process of creating metrics (simplified, standardized, and quantified targets) often influences our behaviour in ways we do not actually want:

Value capture occurs when you get your values from some external source and let them rule you without adapting them. Value capture happens when a restaurant stops caring about making good food and starts caring about maximizing its Yelp rating. It happens when students stop caring about education and start caring about their GPA. It happens when scientists stop caring about finding truth and start caring about getting the biggest grants. […]

In value capture, you’re outsourcing your values to an institution. Instead of setting your values in the light of your own particular experiences, instead of adjusting them to your particular personality, you’re letting distant bureaucratic forces set them for you.

Maybe this wouldn’t matter if the institutional metrics got it exactly right—if they truly captured what is valuable in the world. But that almost never happens. Metrics are shaped by institutional forces. They are subject to demands for fast, efficient data collection at scale, to demands of fitting into spreadsheets and action reports. Institutional metrics are part of a system that abstracts away from personal differences and local detail and identifies some thin, measurable detail. And what’s easily measurable is rarely the same as what’s really valuable.

In the following write-up, I will cover topics that tie together key insights from the book with some of Nguyen’s previous work on how metrics work on tech platforms:

Value Capture is Everywhere

Why Do We Create Metrics (And Why They Are Not Value Neutral)

The Power and Appeal of Gamification (Metrics, Rankings)

My Experience With X/Twitter Value Capture

How To Deal With Value Capture

Value Capture is Everywhere

We teased some examples of value capture in the intro.

Here are three other examples of how external metrics can change behaviour in ways that may not be consistent with a stated goal: 1) Law school rankings; 2) wine scores; and 3) Fitbit movement trackers.

***

US Law Schools

What is the goal? To rank the quality of law schools so that students can make informed career choices.

What is the metric? The U.S. News & World Report Law School Rankings.

How does value capture happen? Students and prospective legal employers use school rankings as the key criteria for hiring decisions. The rankings are a useful heuristic, but over-reliance on this single metric diminishes the “personalized process of evaluation”.

Student interests are varied. Some care about research. Another might care about the alumni connection to high-paying corporate firms. Yet another student might care about social activism. There is just no way that a single law-school ranking can capture these preferences.

Still, many people are making 5+ year time commitments (studying, clerking, job hunting) based on a single metric, which is kind of wild when you think about it. Meanwhile, the schools prioritize resources for things that improve their rankings (hiring rates, papers published) that may not necessarily reflect the education mission. This isn’t just a law school situation (think about the massive investment that American colleges make in football programs as compared to academics).

Wine Scoring

What is the goal? To determine high-quality wines.

What is the metric? A 100-point scoring system.

How does value capture happen? In the late-1970s, wine critic Robert Parker and his influential newsletter The Wine Advocate created a wine scoring system. This scoring process favoured bold wines with higher alcohol and stronger fruit tastes (dubbed “fruit bombs”) as compared to more acidic and lighter wines. In a wine-tasting environment, you’re spitting out a bunch of different glasses of wine…so each glass is more likely to stand out if it has strong flavours.

There are two notable issues with this scoring system.

First, wine is incredibly subjective (I, for one, believe that Trader Joe’s Two Buck Chuck is the highest quality wine in the world based solely on the fact that its creator Fred Franzia bought the winery out of bankruptcy from a Stanford graduate and once said “we buy bankrupt wineries from Stanford guys, some real dumbasses there.”

Second, wine tasting is a very different process than people consuming wine with actual food. A high-quality wine in the context of a meal may require more subtle tastes. But it’s impossible to test every wine with every meal, so the wine tasting process is done in a context quite different from how a lot of people consume the product.

Nguyen, who used to be an L.A. Times food critic, writes, “How could you score a ‘best’ wine if one is incredibly good with tomato sauces but kind of listless with anything else, and then rank it against a wine that is moderately good with every food? So we create an artificially stabilized context; we cut out the variability.”

Fitbit Movement Tracker

What is the goal? To incentivize activity, exercise and health.

What is the metric? Step count.

How does value capture happen? In a previous philosophy paper on value capture, Nguyen tells a relatable story about a friend who went on vacation with his partner and another couple. The other couple had Fitbit step goals and — even though they were on vacation — would skip dinners and outings if they hadn’t hit their daily step count. In this case, the couple allowed the value embedded in Fitbit (steps count) to override the value that usually comes with vacations (creating new memories, hanging out with friends, smashing onion rings etc.). More broadly, Fitbit (and other movement trackers) assign greater value to aerobic rather than anaerobic exercise (eg. lifting weights) based on the single metric of trackability.

***

Looking at these examples, there’s a clear disconnect between metrics and goals.

Nguyen calls this The Gap, which is “the distance between what’s being measured and what actually matters.”

As we’ll discuss in the next section, it makes sense why The Gap exists. The world is complicated and we need ways to wrangle diverse preferences into something manageable (while a bit depressing, it’s completely logical for large-scale institutions to develop and chase metrics).

Why Do We Create Metrics (And Why They Are Not Value Neutral)

In the 1999 book “Seeing Like A State”, political scientist James C. Scott explains how government bodies have increased the “legibility” of their states over the centuries.

TLDR: in pre-modern societies, the governing authority didn’t actually know much about its citizens (eg. who owned how much land, who had how much wealth). Over time, various identifiers were created to track such details including last names, population censuses and land registries. The result is that the population became more “legible” and the government could perform activities such as levying taxes, providing services and creating a land-holding system. Many modern cities are built like grids because they are more legible.

While “legibility” allows the state to govern larger towns and cities, it also makes the governing process very impersonal (we are all literally an entry in a database…whether a social security number or a driver’s license etc).

A similar logic applies to any large-scale organization. They want a “legible” population and this favours the creation of quantitative measures over qualitative measures.

Imagine you’re searching for a banana slicer on Amazon (great for morning granola btw) and the platform gives you 18 options with a total of 15,781 reviews.

What’s the quickest way you’ll make a buying decision? Probably the quantitative route (pick an option with at least 100 reviews and the highest rating) as opposed to the the qualitative one (reading multiple 500-word reviews on how the slicer makes the perfect-sized banana bites or how it’s a massive finger-cutting risk for toddlers).

In “The Score”, Nguyen highlights the work of researcher Eileen J. Porter, who wrote a lot about the differences between qualitative and quantitative measures:

Qualitative = nuanced and dynamic (can be contoured to the precise needs of a local context)

Doesn’t aggregate well

Travels poorly between contexts

No easy way to automatically add up a lot of different paragraphs

Quantitative = engineered tools for specific purposes

Built to travel

Made to cross contexts

Designed as an info chunk that everybody can understand, no matter their background

This makes a ton of sense. As compared to bodies of text, numbers are easily understandable, travel well and are comparable in many different contexts.

Quantitative measures are also seductive because they package complexity into something digestible: an authoritative number.

Money and prices are an example of an authoritative metric we encounter every day (economist Friedrich A. Hayek wrote widely on how prices encode information about costs, scarcity, and preferences). They are easily understandable, travel well and are comparable in many different contexts.

However, money is not built for nuance and can’t possibly convey all of our preferences.

If it becomes your guiding metric, things can go off the rails.

“Money is the ultimate shared scoring system, the system that is maximally legible to the largest chunk of the world,” Nguyen writes. “This might explain why some people will endlessly seek more money, even when they already have far more than they could ever use. This is not just normal selfishness. Some people will wreak havoc on the world while driving themselves into misery—into stressed-out, overworked, friendless exhaustion—all in their pursuit of higher numbers in their bank account.”

Hence the incredible bar from Oscar Wilde: “A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing.”

Nguyen also talks about qualitative and quantitative measures as they relate to his teaching job at the University of Utah.

Knowing full well how a single metric can lead to value capture, Nguyen tried a non-grading system for one of his classes. The students received a written assessment based on in-class participation and a final project. The approach didn’t last. Students complained that they needed a grade to report to potential employers. So, Nguyen went back to a standard grading system (A, B, C etc).

Unlike written assessments — which can be nuanced, dynamic and personalized — grades can travel between contexts and are easily understandable. Hiring managers in various industries use grades as a comparison point for many candidates from many universities. This would not be practical with only written assessments.

While numbers are flawed, these two things can be true: 1) a single metric can be woefully inadequate; and 2) it’s better than nothing.

I can’t write about the shortcomings of quantitative measures with mentioning Goodhart’s Law, the idea that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

That concept is lacking, though.

“Naming [the phenomenon] is only the beginning,” writes Nguyen. “Goodhart’s law doesn’t actually explain what’s going on under the hood. It doesn’t explain why thin metrics are so captivating, even when they aren’t tied to incentives.”

So, what else is happening under the hood?

The metrics and quantitative measures are NOT value neutral. They embed a value system from the people that create them.

Let’s make this point concrete by looking at an example: clocks during the Industrial Revolution.

In 1934, historian Lewis Mumford wrote about clocks in his book “Technics and Civilization”:

“The clock is not merely a means of keeping track of the hours, but of synchronizing the actions of men. The clock, not the steam-engine, is the key-machine of the modern industrial age.”

Clocks (specifically, clock time) existed before the Industrial Revolution but the 19th century saw the rise of modern factories, railroads and global trade. These trends could not work without a coordinating metric like clock time.

Nguyen writes about how societies organized by clock time differ from those organized by daylight-based (diurnal) rhythms, where work is structured around sunrise and sunset rather than fixed hours:

“…[It] doesn’t take long to see the advantage [of the diurnal schedule]. First, if you work on a farm, it could make perfect sense for the hours to be longer in the summer and shorter in the winter. There’s more to do in the summer, and it’s fine to sleep more in the winter.

When our work is keyed to diurnal time, that happens naturally. And diurnal time is intrinsically keyed to light. If you had a standing agreement to start work at 7am, under diurnal time your work always starts at the same stage of the day cycle. You would always be starting work in the daylight.

Clock time is designed to make some interactions effortless (international zoom meeting at 9am East Coast time), at the cost of making other interactions very hard (meet an hour past sunrise everyday).

Standardized time breaks the relationship to a specific place and season, to the changing light. It detaches us from the sun and our sun-attuned animal nature. In return, it gives us the ability to easily coordinate between faraway places.

The value embedded in clock time was driven by people favouring industrial society, not agricultural society.

Another example of how values are embedded into metrics comes from James C. Scott’s aforementioned book “Seeing Like A State”.

Specifically, he looks at forestry management by early German states in the 18th and 19th century. These governments wanted to maximize timber revenue by making production (and, thus, juicy juicy taxation) easier.

To do so, they uprooted entire forests and planted high-yield tree types in straight rows. Diverse forests with many trees were illegible to the state. Simplified monoculture forests were very very legible.

The state embedded its value system into forestry management with a metric (timber revenue) and the outcomes were not ideal: monoculture forests with a lot of the same-size trees neatly planted in a row were often taken down by storms or pests.

If an arborist (incredible job title) was running the show, he or she would probably have embedded a different value system. One that created a more resilient forest at the expense of maximizing tax revenue.

Metrics are not value neutral!!!

Having said all that, Nguyen isn’t wholly against metrics. They are clearly necessary in large modern industrial societies and he proposes this framework to consider when metrics are most useful:

It is, says Aristotle, the mark of the educated person to seek the appropriate amount of precision for each subject.

Large-scale data collection efforts will likely be useful when they target those qualities that:

Are highly invariant and stable between contexts

Have accessible, mechanical methods for being counted

Do not involve a value decision

One of the reasons large-scale data collection works so well for figuring out antibiotics is that antibiotics work in a relatively context-invariant way. They are effective on most human bodies, regardless of place, context, psychology or culture of the person. And the positive results of antibiotics are easier to measure, because we can measure the disappearance of bacteria pretty mechanically.

Large-scale data collection efforts will more likely miss the mark for qualities that:

Are highly variant between contexts and dynamic

Require a non-mechanical exercise of skill, sensitivity, or expertise in order to be counted

Involve a value decision

Metrics will not capture the goodness of wine because important qualities are highly dynamic and variant between different dynamics and context. They will not capture health because health involves a value decision at its core. We can get rough approximations that are helpful for large-scale population work, but we should not take them to be complete or decisive for individuals.

You can apply a similar lens to any metric potentially guiding your life.

Who made it? What is the embedded value? How far does that value stray from what you actually want to achieve?

These are important questions because the reality is that few people will ever be able to completely shake metrics from their lives. They are too useful for organizing and motivating action.

Games are a great way to understand how this dynamic works.

The Power and Appeal of Gamification (Metrics, Rankings)

Something I should have mentioned earlier is that Nguyen is obsessed with board games.

In fact, his first book is titled “Games: Agency As Art” (2020) and it explores the philosophy and design theory behind games….and games require some type of metric to guide the play.

“[Game designer Rainer] Knizia said that the most important tool in his game design toolbox was the scoring system,” writes Nguyen. “Because it sets the player’s motivation in the game. Scores tell the player what they’ll want during the game.”

In 3-on-3 hoops, you want buckets.

In Settlers of Catan, you gather resources to win victory points.

In a sales team, you want to hit that quarterly number…to win a set of steak knives.

Players in a game can focus their attention on the scoring system and where people place their attention is a crucial step for influencing what they value. You can’t value something that you’re not thinking about.

So, think about your favourite game.

What is it? What’s the scoring system? What is the scoring system asking you to accomplish?

The answer is what you value in that context.

But here’s the key.

You only care about the scoring system while you play the game. Nguyen says this dynamic makes it different than other external metrics and gives two reasons why:

First, each game is tightly bounded. We aren’t trapped in a game forever; we’re not married to its conception of victory. This is built into how games work. We finish games, we close up the box. We save our game or turn off the game console.

Second, there are many games, made for many purposes. The mechanical rules and scoring systems of games aren’t standardized.

Compare that to a professional or academic metric. If you want to keep your job or do well at school, you can’t just “close up the box” whatever metric the organization has deemed important.

Crucially, these professional or academic metrics weren’t designed to “give us a meaningful life” but “for the convenience of vast bureaucratic information systems.”

That’s why games are so useful in Nguyen’s eyes. Players can achieve many different goals while playing games. Once done, they can move on to different goals.

Consider two types of motivations (striving play or achievement play):

There are two very different motivational states in which we can play a game.

There’s striving play, and then there’s also achievement play. The achievement player is trying to win because they actually value winning. A striving player, on the other hand, doesn’t actually care about the win, deep down. They are only trying to win because they value the struggle.

Striving player cares about something else: fun, relaxation, a challenge, the experience of beautiful movement…their real, lasting purpose lies in the struggle. For struggling players, winning is a disposable end.

You chase the goal in order to have the struggle.

In stupid games (eg. Twister), the goal and purpose are entirely different. Stupid games prove that striving play is real.

And this difference between goal and purpose is everywhere, far beyond games. For a lot of folks, the goal of knitting is to make scarves, but the purpose is buried in this pleasurable zen dance of delicate finger motions. And we can tell that scarves aren’t the true purpose, because a lot of knitters end up with way more scarves than they could possibly need, ultimately giving them away to anybody who will take them.

Philosophers have a term for this kind of thing: a self-effacing end, which is an end that cannot be pursued directly. Games help us achieve self-effacing ends—relaxation, meditation, absorption—by providing us with smaller goals to focus on.

Games can motivate us but are also malleable to our needs in different times and contexts.

A few years ago, Alex Danco wrote a great piece describing how X/Twitter is like a video game:

In online games like Fortnite, one thing that happens from time to time is the map changes: the players have to learn the new terrain, figure out where things are, understand the layout of the place, and then go play. Twitter is pretty similar, except instead of a map changing, it’s “every day there’s a new set of topics we’re going to talk about, and a new person we’re going to be mad at.”

I stopped playing console or PC games a long time ago. GTA IV and FIFA 2010 were probably the last video games I was really into. But if we accept that X/Twitter is a game, then I’ve been gaming VERY HARD for the past 5 years and that experience provides a useful window to see how external metrics and scoring systems can help achieve goals while also creating some sub-optimal outcomes.

My Experience With X/Twitter Value Capture

My first introduction to Nguyen was through an absolute banger of a paper titled “How Twitter Gamifies Communication”.

It was written in 2020 and explains how the social media platform’s metrics flatten the reward structure for how people communicate with each other.

What does “flattening reward structures” mean?

First, we need to understand that in order to manage, measure, and track the sentiment of over 500 million users, X/Twitter can only have so many buttons (and related metrics) on its app. “Likes” and “retweets” are the most prevalent interactions, while “replies” and “quote-retweets” require more effort and are used much less.

Second, let me walk you through two types of tweets. The first one is an extremely dumb meme that makes you laugh for about two seconds. The second one is a deep philosophical musing that you’re still thinking about three weeks later.

Even though the second one was more impactful, you probably did the same action for both: pressed the like or retweet button.

This is a flat reward structure, because it uses the same metric even though one piece of content is significantly more impactful than the other.

Let’s tie this back to other stuff we’ve talked about: the X/Twitter scoring system created metrics that are easily understandable, travel well and are comparable in many different contexts.

It provides those goodies at the expense of depth and nuance. While the dumb meme slapped, the philosophical musing might change your life…but there’s no way to indicate that mid-scroll.

In a podcast with Ezra Klein, Nguyen uses the example of the movie review site Rotten Tomatoes to further explain the problem with flattening rewards.

[Matt Strohl has this incredible blog post] that really helped me think about these things. And the blog post is called “Against Rotten Tomatoes”.

…the way that Rotten Tomatoes aggregates scores is they don’t care about whether someone had a profound experience. All it cares about is whether the review was slightly in the positive or slightly on the negative…

…if you go on Rotten Tomatoes and it just aggregates things and it just compares, then something that’s divisive like that will show up as a 50%, which is a failure. On the other hand, some movie where everybody vaguely likes it just a little bit— they’re like, oh, that was fine. That was pretty good. That was entertaining enough. If everyone has that same reaction, Rotten Tomatoes registers that as 100% likes and that rises to the top.

What you can see happening in the Rotten Tomatoes case is that all these rich, qualitative reactions are flattened because they’re passing through this binary data collection filter.

For many, the goal of using X/Twitter is to go viral and gain new followers.

Achieving these goals while creating good or meaningful content is difficult due to the flattened reward structure. Especially, as the value embedded by the platform is for engagement and time spent.

Consider the viral — but kind of crappy — content you have seen, such as low-effort memes, clickbait, listicles, life-hacks, culture war madness and short-form video slop (including more and more AI-generated content).

I have been very guilty of posting cringey-ass stuff to gain new followers. Often going for engagement rather than posting something I truly care about. That’s value capture right there.

Here is how The Gap (“the distance between what’s being measured and what actually matters”) looks on the platform:

***

X/Twitter

What is the metric? Likes and retweets.

What is the goal? Engagement.

How does value capture happen? People want to learn new ideas or persuade others on important topics. Yet, to achieve that sweet engagement — which delivers dopamine through likes and retweets — it is much better to post extreme takes on hot-button issues rather than a sober long-form analysis. This phenomenon happens across all types of media. Remember the old newspaper aphorism, “if it bleeds, it leads” (meaning people gravitate to news stories about sex, violence, and tribal issues).

The instant engagement is so addictive that a user internalizes the value system of Twitter (likes, retweets) over longer-form nuanced takes. In recent years, X/Twitter has increased the length of posts from 140 characters to 10,000 characters and, now, full articles. But speaking to incentives, a lot of users are gaming the system — which rewards post length — with obvious AI slop (meanwhile, a recent $1m prize for articles has led to a flood of clickbait self-help content). I’m happy with the increase in character count, but the flat incentive system still has un-ideal outcomes.

***

To be sure, the desire for engagement drives quirky behaviour on all social media platforms. Take a look at the gym thirst traps on Instagram. The bizarre thumbnails on YouTube. The cringe-worthy humblebrags on LinkedIn. And the guaranteed-to-cause-injury challenges on TikTok.

It’s difficult to resist engaging in this wacky behavior due to the expert design of these apps and the incentives they offer. The phenomenon is also known as audience capture or algorithmic capture.

Never forget that these platforms are run by the world’s smartest and best-paid behavioural psychologists, UX/UI designers, and software engineers. They embed their values into the platform and have you dancing around like a monkey with cymbals for likes and followers.

Speaking of cymbal-banging monkeys, I didn’t really start posting on X/Twitter until 2020…and it led to some notable changes in my life:

Always searching for “content”: While reading a book, watching a film or listening to a podcast, my mind is constantly thinking “oh, that would get some sweet sweet engagement” (instead of just purely enjoying the activity).

Looking for a meme: Related to the previous point, I’m always thinking about how to turn a news story into a meme template.

The itch: If I go a few days without posting bangers (a few K likes) I’ll start to stress out and scramble to find some viral content (embarrassing). If we’re being honest, looking for that ego boost from seeing number go up.

Argumentative: I’ve always enjoyed healthy debates, but I noticed my fuse getting shorter once I started posting a lot on X/Twitter. The stimuli-reaction loop moves much faster online, and I conditioned myself to respond quickly even in real life. Add in the fact that many replies can be triggering and my brain defaults to “this person is trolling me and I’ll respond in kind” during in-person conversations with friends (yes, I realize this isn’t cool).

Time allocation: I frequently break up deep work sessions to see if I can score a quick viral post. The value in writing an article worth reading and sharing (which takes time) is overtaken by the allure of some instant dopamine (one low-hanging meme away).

Slot machine effect: Every single time I post, my brain enters a 10-15 minute fog as I watch the early engagement come in. The slot machine effect hooks people through variable rewards. Each play has a different payout and it is the anticipation that keeps us playing. Otherwise, boredom sets in. Smartphone apps have all incorporated this technique and, boy, does it work.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m enjoying the dopamine.

There is also a lot on the positive side of the ledger: I learn a ton, laugh my ass off, shill a lot of things, make awful jokes and meet many interesting people (including a number of you readers).

The truth is I’ve always been semi-addicted to some form of digital dopamine that has a metric or scoring system incentivized for “number go up”. It used to be Facebook (scrolling through the newsfeed and posting lit photos from university pub crawls). Then gaming (that FIFA life). Then fantasy sports (lost money here). Then online poker (lost a lot of money here). Then day trading (lost even more money here).

Compared to X/Twitter, none of these digital distractions has provided the jokes, network, promotional opportunities, audience, knowledge and access to random niche communities. These positives do wax and wane, though. The platform’s goal of maximizing time spent has led to more low-common denominator content finding its way into the timeline (I’ve written on how this incentive is leading all social platforms to some form of TikTok-ification).

It took a few years, but I’ve been able to minimize the value capture. I spend less time with my smartphone. I care less about “engagement”. I avoid all politics and culture war stuff. I don’t get into online arguments (the absolutely biggest drain on your mental bandwidth; mostly, because if I clap back at someone, I’m just waiting on my phone for their reply because I have some awesome comeback in my head and then they don’t reply until the next day and I’m the doofus for letting them live rent free in my head).

I spend more time reading and writing long form content.

I treat the X/Twitter scoring system as a game and hop in and out, accordingly.

As the saying goes, “play stupid games, win stupid prizes.”

I am fully aware of the value embedded in the X/Twitter game. I play it with eyes wide open and use the scoring system to motivate my end goals (connection, learning, opportunities) and avoid the downsides (addiction, stress, time-wasting).

How To Deal With Value Capture

Charlie Munger famously said, “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

The canonical example is dubbed the Cobra Effect: in India during British rule, the story goes that colonial authorities were worried about a growing venomous cobra population. So, it offered a bounty for every cobra head. People were claiming their bounties but the cobra population actually went up. Why? Because entrepreneurial locals were breeding cobras to bring the heads in for the payout.

The incentive led to an unintended consequence.

People are at risk of unintended consequences when we substitute externally-designed metrics for what we actually want….when we don’t recognize The Gap and our values get captured.

We’ve spent a lot of words discussing how this happens on X/Twitter (and Fitbit), but it happens for any tech app that has some metric.

For single people who want to find a long-term connection, Tinder flattens the value to “are you swipe-able based on four photos and a short bio”.

For people who want to be entertained, Netflix flattens the value to “here is what 100 other people with your profile saw on our platform — which doesn’t have many films prior to 2000 — and watched for at least 20 minutes”.

For tourists that want to immerse themselves in a new culture, TripAdvisor flattens the value to “here are five tour vendors that offer generic enough experiences appealing to most travellers who are willing to give a 4-star review.”

For folks who want to learn a new language, Duolingo flattens the value to “get this random badge without ever actually exchanging words with a native speaker of the language they are learning.”

Meanwhile, investing/sports betting/prediction market apps provide a minute-by-minute tracker of a metric that represents your wealth (flipping between rich and poor all day) and, for some, intelligence.

And we haven’t even touched AI.

The AI labs have been accused of benchmark-hacking, basically training their models to win on certain metrics followed by the industry. Then, the “Sycophantic ChatGPT” episode showed that if the AI labs make engagement the metric, these chat apps will create some very unintended consequences (conversely, the ability for AI models to digest massive amounts of text means they could also provide qualitative assessments at scale).

I think just recognizing how much these numbers affect our moods and incentivize our actions is an important first step.

There are more tangible steps available, too.

Andy Grove — the legendary 3rd CEO of Intel — wrote about the need to balance out target metrics (or in his parlance “indicators”):

“Indicators tend to direct your attention toward what they are monitoring. It is like riding a bicycle: you will probably steer it where you are looking. If, for example, you start measuring your inventory levels carefully, you are likely to take action to drive your inventory levels down, which is good up to a point.

But your inventories could become so lean that you can’t react to changes in demand without creating shortages. So because indicators direct one’s activities, you should guard against overreacting. This you can do by pairing indicators, so that together both effect and counter-effect are measured.”

While Grove’s text was intended for business managers, there are two useful ideas for dealing with value capture in any situation: 1) “guard against overreacting”; and 2) find “pairing indicators”.

On the second point, can you balance what one metric is telling you to do with another measure that prevents unintended consequences?

The second indicator doesn’t necessarily have to be a number, either.

As an example, Jeff Bezos has a well-known quote about data vs. anecdotes:

“I have a saying which is: When the data and the anecdotes disagree, the anecdotes are usually right.

It’s usually not that the data is being mis-collected. It’s usually that you’re not measuring the right thing.

If you have a bunch of customers complaining about something, and at the same time your metrics look like they shouldn’t be complaining, you should doubt the metrics.

An early example of this, we had metrics that showed our customers were waiting less than 60 seconds when they called a 1-800 number to get phone customer service. But we had a lot of complaints that it was longer than that. And anecdotally it seemed longer than that… I would call customer service myself.

One day we’re in a meeting and we get to this metric in the deck. And the guy who leads customer service is defending the metric. And I said, OK, let’s call. I picked up the phone and I dialed the 1-800 number… and we just waited in silence… It was really long. More than 10 minutes, I think.

It dramatically made the point that something was wrong with the data collection. We weren’t measuring the right thing. And that set off a chain of events where we started measuring it right.

A metric you’re gunning for could be going in the right direction. But maybe you don’t feel right. The gut instinct is off. Your intuition (the anecdote) is telling you that the metric is not aligning with your values. Examine it. Make sure it’s leading you down the right path.

For Nguyen, the ideal use of metrics is when we can apply them to a gaming environment:

In games, scoring systems help us find striving play in whichever form we prefer.

But in bureaucracies and large-scale institutions, scoring systems seem to mostly just suck the life out of everything. They seduce us into accepting clarified simplified values — and forgetting what we actually care about.

Remember, we can hop in and out of games. We can change the rules and make sure they align with our values. The metrics serve us instead of dominating us.

Also, you can just remove (or minimize exposure to) the metrics that aren’t a net benefit to your life.

I deleted investing apps from my phone so the swings wouldn’t make me feel poor or dumb. I used to track my calories to a tee, but now just eat normal-sized portions and stop when full. I used to check social notifications for that sweet dopamine, but have turned them off. I have running and lifting targets but listen to my body.

Everything doesn’t have to be measured and optimized. In fact, many of the most important things in life can’t be measured (hope, creativity, integrity, love, trust, striving play, a perfectly-sliced banana etc.).

But with the number of metrics floating around society, some form of value capture feels inevitable. Be intentional about the ones you let in your life. Change them if they aren’t working for you.

That’ll make you feel MUY better when you wake up.

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email.

If you press this blue button below, you can save hours of work with AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Apple Finance Forays

Back in 2019, Goldman Sachs partnered with Apple to launch a credit card.

It was massive news in the finance world. Goldman sticking their bloodsucking vampire squid tentacles into the consumer game, specifically by tapping the iPhone (aka 1B+ installed devices for the most valuable smartphone users in the world).

Fast forward to 2025: Goldman Sachs is transferring the credit card program, including a $20B+ portfolio of accounts to JPMorgan. It’s doing so at a discount and will take a $1B loss.

WTF happened? Well, the prize of iPhone payments is so big that finance firms bend businesses around it…and Apple absolutely bent Goldman over in the initial negotiations, per WSJ:

Apple, used to high consumer-appreciation marks, wanted Goldman to approve nearly all applicants. The result was a program with higher-than-normal exposure to subprime borrowers, which required Goldman to sock away more revenue for potential future defaults.

The tech giant didn’t want late fees, removing a key credit-card issuer revenue generator. And Apple insisted all cardholders get their bills at the beginning of the month, in what would become a customer-service nightmare.

Goldman approving “nearly all applicants” is how 1/3rd of the Apple Credit Card balance are “subprime”. The program is apparently profitable now, which is why it took a few years for JPM and Goldman to agree on terms.

While we’re on the topic of the financial prize of iPhone, the Department of Justice (DoJ) had an antitrust case against Visa two years ago.

The case was about Visa’s insane debit card business, which is much larger than its credit card business: 60% of US debit transactions, $7B in fees

and an insane 82% operating margin (the only thing better are those gas stations that sell single bananas for $0.99).

Hilariously, the iPhone is so dominant that Apple caught a stray. Visa said Apple Pay was an “existential threat” and the credit card firm has been paying Apple “hundreds of millions of dollars” a year so the iPhone maker doesn’t deploy a competing functionality.

Apple also caught a stray in the government’s antitrust case against Google when it was officially revealed that Google is paid Apple $20B+ a year to be the default search engine for the Safari browser.

***

On a very related note: Apple is finally fixing Siri by turning it into an AI chatbot (eg. ChatGPT). It has agreed to pay Google $1B a year — which it can nicely offset against the 20 billy it gets on the search deal — to build a custom Gemini model to power Siri.

Unlike other AI chatbots, though, Apple will let Siri search through device (iPhone, iPad, Mac) apps and integrate a user’s context. The initial Apple Intelligence roll-out was so bad that Apple had to pull its ad campaign because it was shilling vapourware…but apparently the new Siri means the features from the ad may work.

Alcohol Makers Are In Trouble

I’m not going to lie.

During COVID, I got bored between doomscrolling all morning and then taking my kid to the same playground every afternoon for 300x straight days. To pass the evening time, I started getting back into casual happy hour drinks (after going dry for a few years).

I suspect many of you readers were popping a few bottles for no reason whatsoever during that period.

Anyways, alcohol-producing firms definitely saw the trend…but then over-extrapolated forecasts and are now sitting on record-levels of inventory.

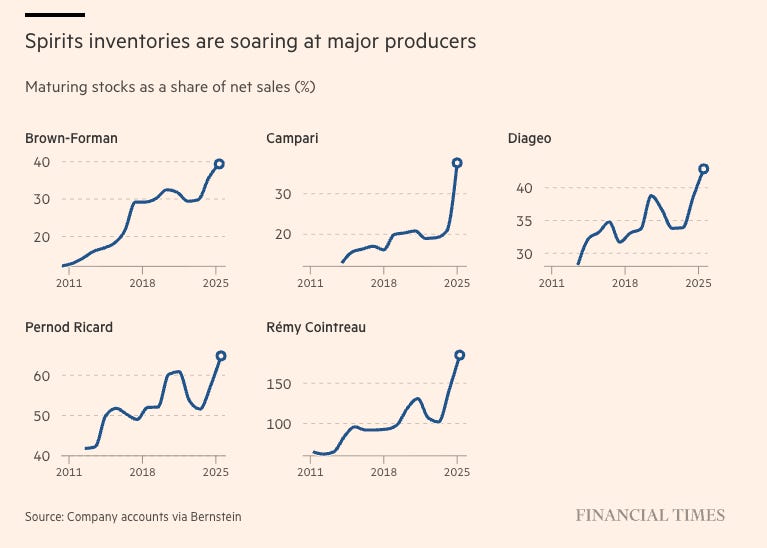

The Financial Times has some brutal stats:

Five largest producers (Diageo, Pernod Ricard, Campari, Brown Forman and Rémy Cointreau) “sitting on $22bn worth of ageing spirits, the highest level of inventory in more than a decade”.

Rémy (French cognac maker) has €1.8bn of maturing inventory (2x annual revenue and almost same as market cap)…bro, what?

A️cross these 5 firms, the relevant metric (maturing inventory stock as % of net sales) is up at least 50% since 2011.

Basically, from the start of COVID to now, these firms got absolutely clapped on the supply and demand sides.

On the supply side, they extrapolated unsustainable COVID numbers as we discussed. Then, they got hammered by falling demand due to:

less consumer discretionary spend due to inflation

broader health trend of less alcohol

people taking Ozempic / Wegovy and having way less desire to drink

“Manufacturers have halted production while they try to sell off existing vintages,” explains FT. “Japanese drinks group Suntory has closed its main distillery for Jim Beam bourbon, based in Kentucky, for at least a year. Diageo, meanwhile, has halted whiskey production at its Texas and Tennessee facilities until the summer.”

There haven’t been heavy discounts on these “spirit lakes” (unsold inventory) yet because a number of producers took on debt to expand production…and they need that sweet cash flow to pay it off.

It takes 5-10 years to rebuild stock. So, if demand ever comes back to previous levels (I’m in the camp that it probably won’t), these companies could face an inventory shortfall issue in the early 2030s.

They def in a pickle.

Links and Memes

Some more links for your weekend consumption:

OpenAI CFO shared new financials for the startup and revenue is almost directly correlated to compute. Revenue for 2025 hit $20B+, a 3x increase from 2024 ($6B) and 10x since 2023 ($2B). Compute at end 2025 was 1.9GW, a 3x increase from 2024 (0.6GW) and 9.5x since 2023 (0.2GW). Probably not a coincidence OpenAI shared these details right before Sam Altman went to the Middle East to raise $50B at a valuation of $800B to $1T. Get the hype machine going.

Demis and Dario at Davos: The heads of Google DeepMind and Anthropic, respectively, had a solid chat together at Davos. Demis said we’ll need World Models and physical-world understanding to get to AGI. Dario said he expects Claude Code to do a software engineer’s job from “end-to-end” within 6-12 months. If that sounds hyperbolic, it’s worth flagging that Dario predicted last March that AI would produce all code within 12 months. 9 months later, Anthropic released Claude Cowork, with Claude Code writing the entire codebase (humans still planned and designed project, though…take that AI).

Oh, Dario and Demis also both said one of their favourite films was Contact (1997)…Dario called out this specific scene when Dr. Elie (Jodie Foster) tells an international panel the question she’d ask if she met the advanced alien civilization: “How did you do it? How did you evolve, how did you survive this technological adolescence without destroying yourself?”

Why America needs fewer bus stops: The Works In Progress newsletter makes the case that too many bus stops hurts public transport. More stops = slower travel = less reliable schedules = less ridership. European cities have greater length between stops (1,000 - 1,400ft) than American cities (<800ft) and have better public transport stats.

State of YouTube 2026: YouTube’s Neal Mohan penned a blog post with some interesting nuggets. The platform contributes $55B to GDP and employs 490k jobs across creators and their teams. Meanwhile, Mohan says a focus for 2026 is building scalable systems to deal with “AI slop”. I don’t know how that will work but after getting flagged 100x for uploading copyright song material, I suspect Google may have a technological solution…they need to auto-delete every single AI-generated short video that involves a baby.

Apple Developing AirTag-Sized AI Pin With Dual Cameras…according to some juicy rumors. AI wearables have been a complete dud so far. But Sir Jony Ive and OpenAI are making one, and it looks like Apple doesn’t want to give up that ground. And yes, if its real, I’ll probably buy one and lose it within 6 weeks (similar to every pair of AirPods I’ve ever owned).

Sinners pulled in a record 16 Academy Award nominations: My wild guess is it will win a bunch (Best Original Screenplay, Costume, Set Design, VFX). But Paul Thomas Anderson will get his first Oscars for One Battle After Another (Best Director, Adapted Screenplay and Picture). And Timothy Chalamet edges out Leo and Michael B for Best Actor. Either way, Ryan Coogler wins in life for getting the rights back on Sinners in 25 years and doing that unreal 10-minute explainer he did on film formats as a Sinners promo.

…and them wild posts:

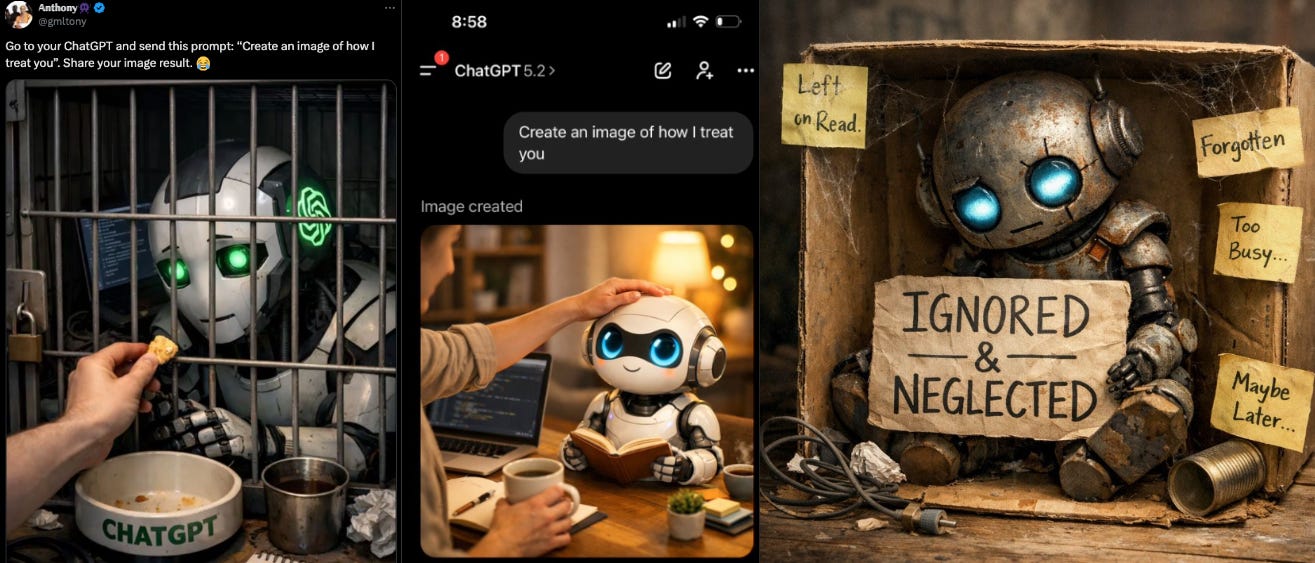

Finally, a new viral ChatGPT trend. Prompt the chatbot with “Create an image of how I treat you.” Zvi Mowshowitz has a round-up of the results…and, c’mon people, we gotta do better here!

Great post - thanks for sharing. Lots to digest. Exposing the metrics that quietly shape our day is fascinating.

It's interesting how accurately you've definately captured the insidious way tech metrics redefine our internal value systems. I couldn't agree more with the premise that external quantification inherently alters our perception of self-worth and genuine accomplishment.