The Dorito-fication of Media

How the evolution of media created ultra-processed junk food for our mind.

Thanks for Subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about the invention of the Doritos chip and what it can tells us about the future of our media diets.

Also this week:

Temu vs. Amazon

When Intel almost bought Nvidia

…and them fires posts (including a very good Halloween costume)

This issue is brought to you by Liona AI

Launch a GPT Wrapper in Minutes

As many of you SatPost readers may know, I’ve been building a research app for the past few years (Bearly AI).

Over that span, I’ve drank over 677 sugar-free Red Bulls while my co-founder built a flexible backend to manage all of the major AI APIs. We turned that backend into a product called Liona AI.

This easy-to-use platform lets your users and teams connect directly to OpenAI, Anthropic, Grok, Gemini, Llama, Cursor and more while you maintain complete control over security, billing, and usage limits.

This is my favourite tweet about the modern-day food industry:

A Doritos chip would melt the mind of a peasant in the 1400s. You know what else would melt the mind of a peasant (or King) in the 1400s? A 10-minute session scrolling through TikTok. Literally, their minds would explode with an iPhone projecting 460 PPI videos into the retinas and spatial audio into the eardrums (do not — I repeat: DO NOT — show people from the 15th century how an incognito browser works).

It is not just people from the 1400s. Honestly, the vast majority of the ~120 billion people who have ever lived on this earth would be shocked by the abundance of calorie and media options available in the 21st century.

For food, the abundance has been necessary to feed a growing population. But by addressing that issue, industrial production of calories has led to an obesity crisis and related healthcare costs.

A similar problem is happening with digital media. Social apps — largely accessed through smartphones — have helped us communicate, learn, stay connected and be entertained. But it’s accomplished these ends by hacking our attention and potentially creating mental health issues.

We’ve been trying to clean up our food diets for decades and there is a growing realization that we need to do the same with our media diets.

Author Cal Newport wrote about this food-media analogy in an article titled “Ultra-Processed Content”, which itself was a riff on a book titled “Ultra-Processed People: Why Do We All Eat Stuff That Isn’t Food…and Why Can’t We Stop?”

“The problem with ultra-processed foods is that they’re engineered to hijack our desire mechanisms, making them literally irresistible,” writes Newport. “The result is that we consume way more calories than we need in arguably the least healthy form possible. Give me a bag of Doritos (a classic ultra-processed food) and I’ll have a hard time stopping until it’s empty. I’m much less likely to similarly gorge myself on, say, a salad or baked chicken.”

Newport then compares the evolution of media to different eras of food production:

Text-based media: This is comparable to minimally-processed whole foods (grains, fruits, vegetables, meats). Humans have eaten this type of food for thousands of year. In this analogy, we’ve been working with some form of reading for over 5,000 years. All things equal, eating whole foods rather than junk food will make us feel better while “consuming writing tends to make us feel better [than other types of media], and we rarely hear concerns about reading too much.”

Electronic mass media: Newport puts the major types of mass media that proliferated from the 1950s (radio, TV) through to the early internet (podcast, blogs) into the moderately-processed foods. In the analogy, these are comparable to white bread and canned soups, which are “easier to consume and much more superficially palatable”. While this content can be valuable, “the ease of its delivery requires vigilance to protect against over-consumption.”

Social media: This most recent crop of media is comparable to ultra-processed foods with their “lab-optimized hyper-palatability”. The design of smartphone social apps powered by recommendation algorithms deliver “hard to resist combinations that will appeal to users”.

“In this way, the users of social media platforms simulate something like the food scientist’s ability to break down corn and reconstitute it into a hyper-palatable edible food-like substances,” Newport writes to complete the comparison. “What is a TikTok dance mash up if not a digital Dorito?”

I am such a fan of Newport’s food-media analogy that I decided to do two things. First, I prompted this extremely dumb AI image of “a smartphone shaped like a Doritos chip made out of a Doritos chip”.

Second, I decided to see how far I could take this “digital Doritos” analogy. So, stick with me as we discuss the history and science behind Doritos and what it may tell us about the future of digital media including:

Inventing the Flavour Industry

Why Are Doritos So Addictive?

TikTok, MrBeast and the Dorito-fication of Media

The Mismatch Theory and What We Can Do

Inventing the Flavour Industry

In his 2015 book, “The Dorito Effect”, Mark Schatzker writes about how industrial food production in the mid-20th century led to the rise of the flavour industry including massive companies that create chemical and spices to improve the taste of food.

One stat that stands out: the average American went from consuming 0.5lb of spices a year in 1918 to more than 3.5lbs of spices a year in the 2010s.

Why has there been such a growth in the use of spices? Because the industrial production of food creates relatively bland ingredients (vs. organic or small farm operations).

Conceptually, this makes sense. Producing food for larger and larger populations requires trade-offs that often come at the expense of taste. Food producers prioritize other considerations such as speed (how fast can it grow?), size (how much volume can it be given X inputs?) and resilience (can the product survive travel to market?).

“As [crop] breeders selected moneymaking traits like yield, disease resistance, and a thick skin for easier transportation, they ignored the genes that determine good flavor,” writes Schatzker.

A notable outcome of these trade-offs is that produce and meats hold more water, leading to flavour dilution (more water weight also means less minerals and vitamins).

Small-batch food growers don’t have to make these trade-offs and that is why their tomatoes, kales, chicken, and pork typically tastes better.

To counterbalance these taste-diluting effects, the food industry spearheaded the chemical creation of specific food flavours (“vanilla”, “smoked”, “orange”, “delicious delicious beef pho” and more).

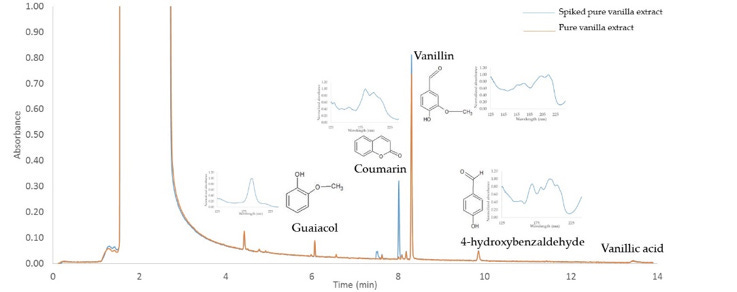

A catalyst for the taste industry was the creation of an analytical technique in the early 1950s called gas chromatography. Invented by chemists Richard Synge and Archer Martin, this new lab process made it possible to separate out the individual chemicals compounds of a substance (eg. food, drugs).

A salient example of how gas chromatography changed the food industry is the invention of Imitation Vanilla.

The main character for this product’s development is McCormick & Company, a spices and seasoning company that is currently worth $20B+ and owns French’s Mustard, Frank’s Red Hot Sauce and a bunch of those little bottles that your wife makes you buy on your last trip to the grocery store to fill out the pantry (whole black pepper, bay leaves, ground ginger, onion powder etc.)

Up to the late-1970s, McCormick sold vanilla extract and the process to…errr…extract the flavour was arduous:

Making [vanilla extract] requires cultivating vanilla orchids, pollinating the blossoms by hand, waiting for the beans to ripen, picking them at just the right time, boiling them in water, “sweating” them in hot chests or tanks, setting them out every morning to bake in the sun until they’re dried, and then conditioning them in closed boxes for a period lasting months, at which point the beans—which are now as moist as a raisin and as long and dark as a cigarillo—are shipped to Europe, then to New York, and then to an extraction plant, where they’re chopped into tiny pieces and alcohol is passed over them continuously in a process of steeping that can take more than a day, and finally held for weeks so the brew can “settle.” It takes a year and half to go from orchid blossom to extract, a single ounce of which costs as much as a shot of good single-malt whiskey.

The main source of these vanilla beans was Madagascar. But political upheavals in the African country during the decade led to a sharp decrease in supply of the crop and prices went up.

McCormick needed a back-up plan. An alternative to vanilla beans was actually developed a century prior in the 1870s by a Frenchman named Friedrich Haarmann. Looking to create a synthetic vanilla scent, Haarmann found a way to isolate vanillin — the key extract from vanilla beans — from different sources including pine cones and clove oils.

However, the flavour profile was quite simple and didn’t capture the real vanilla magic. The problem with vanillin is that it lacks the full aromatic range of real vanilla (I can’t believe I just wrote “aromatic range”). Real vanilla includes aromatic notes such as “woody”, “rummy”, “smoky”, “watermelon” and “resinous” (I can’t believe I just wrote “aromatic notes”).

“If vanilla is a densely layered classic novel,” writes Schatzker. “Vanillin is a comic book.”

McCormick used vanillin as a stopgap for its vanilla extract shortage but wanted to create a proper imitation vanilla flavour.

Enter gas chromatography: McCormick scientists were able to identify and isolate all of the chemical compounds that created those vanilla notes. By 1982, McCormick was selling an Imitation Vanilla which required zero vanilla beans (in fact, the imitation product had only 30 compounds while real vanilla beans have 100 compounds).

To be sure, gas chromatography has many applications. The technique is used for pharmaceutical research, forensic science, environmental monitoring and countless other applications.

Specifically for the food, the manufacturing of tastes, scents and flavours have grown into a ~$50B industry.

“In 1965, there were less than 700 of these chemicals”, Schatzker says of the flavour compounds including those found in apples, cherries, carrots, and beef. “[As of 2015'], there are more than 2,200…But don’t think of it as a list. It’s more like a vocabulary, because these chemicals are mixed and blended in an almost endless combination to produce knockoffs that keep getting more complex, layered, and convincing.’”

One of the most iconic combinations — and by “iconic”, I mean how many times I’ve eaten them while watching Netflix — is Doritos.

Why Are Doritos So Addictive?

The Doritos story begins in the early 1960s at Disneyland.

A Mexican restaurant inside the theme park (Casa de Fritos) took unused tortillas, cut them up and fried them before adding seasoning to create a corn chip.

Arch West — a marketing executive for snack manufacturer Frito Company (now Frito-Lay) — stumbled on the product and pitched it to his company. The idea was to create a chili-and-cheese flavoured tortilla chip that could be mass-produced and sold in packages. That item was called Doritos, a contraction of the Spanish word doradito (which means little fried and golden thing).

Doritos entered the market in 1964 with a Tex-Mex option but the brand didn’t take off until the launch of the Nacho Cheese flavour — which was produced with the assistance of gas chromatography — in the early 1970s.

By that time, Frito-Lay had merged with beverage maker PepsiCo. Today, that company sells $5B+ of Doritos a year including Cool Ranch, Flamin’ Hot and — my favourite — Ketchup (perhaps the most obvious giveaway that I’m Canadian).

If you’ve ever had Doritos, you know these chips are crack. It’s impossible to eat just a few. And that super-concentrated dust on your fingers afterwards will send you into another dimension. Why is the chip so addictive? From the ingredients to cooking method to texture, its engineered to pull all the psychological levers to make you crave the snack:

Flavour mix: Thanks to the flavour-isolating power of gas chromatography, a Doritos chip is dusted with a long list of taste enhancers (MSG, sugar, salt, disodium inosinate / guanylate, garlic/pepper/tomato/onion powder). This perfectly-calibrated mix creates a phenomenon called “non-specific aroma”. No flavor is dominant enough as to cause the sensation of satiety or feeling full. As a result, a snacker doesn’t get sick of a single overwhelming flavour. Coca-Cola has a similar property whereby it doesn’t create a strong “taste memory”. A drinker can’t nail down a single flavour and, therefore, it is difficult to get tired of the product (Warren Buffett often brings this point up when talking about Berkshire Hathaway’s decades long Coca-Cola investment).

Saliva Triggers: Doritos have lactic and citric acid. Both of these ingredients get your saliva flowing, which increases your desire to eat food. You know what else makes you salivate? Cheese and Doritos have a ton including romano, cheddar and parmesan. The company requires the milk from 10,000 cows a year to make enough cheese.

Ideal fat content: A common junk food trait is the combination of fat and sugar. In nature, these compounds are rarely found in combination. There are a myriad of ways to mix them in standard cooking but the snack industry turned the combo of sugar and fat into a science. Speaking of fat and sugar, Doritos have nearly a perfectly balanced mix. The top two ingredients are corn (carb; each bag has three ears of corn) and vegetable oils (fat). The calories in a Doritos chip is split almost exactly 50/50 between carb and fat.

Cooking method: Humans have developed a craving for compounds that come out of the cooking process. Doritos satisfy this craving by hitting you with multiple levels of cooking: 1) the corn kernels are boiled; 2) the boiled corn is mashed into paste; and 3) the corn paste is toasted and deep fried.

Contrasting texture: A Doritos bite starts with a crunch. But it quickly dissolves in your mouth. This is a phenomenon known as “vanishing caloric density”. The feeling of food vanishing in your mouth signals to the brain that you “need” more food (so devious).

If you needed to deliver a calorie with the end goal of increasing repeated consumption, you would probably invent the Doritos chip. As discussed, gas chromatography was crucial for this snack creation because of how it identified the key flavour inputs.

In the next section, we’ll walk through the comparable buildings blocks for the “Doritos of digital media”?

TikTok, MrBeast and the Dorito-fication of Media

Bo Burnham has one of the best insights on the business of social media. During a conference panel in 2019, the musician comedian said:

"[Social media firms are] coming for every second of your life...And it's not because anyone is bad, it's not because anybody in this company has evil plans or is trying to do this, they're not even doing it consciously. Their entire model is growth. They’re coming for every second of your life. We used to colonize land. Then they realized [let’s go after] human attention. They are now trying to colonize every minute of your life."

TikTok — which launched in 2016 — was still an up-and-comer when Burnham made those comments. But the Chinese-owned app saw usage explode during the pandemic. There are a lot of surveys on daily social app usage and this one from Sensor Tower is pretty representative:

TikTok: 95 minutes

YouTube: 74 minutes

Instagram: 51 minutes

Facebook: 49 minutes

X/Twitter: 29 minutes

Snap: 21 minutes

In the 21st century, our attention is the most scarce asset and these companies employ the world’s top engineers, designers, product marketers and UI/UX experts to spend hours a week in their digital worlds.

Even if you don’t use TikTok — which is owned by Chinese tech giant ByteDance — you have probably heard about the app’s very effective design and recommendation algorithm. The best text to understand TikTok’s secret sauce comes from Eugene Wei, a tech veteran and widely-read industry commentator. It’s impossible to summarize Wei’s three-essay explainer on TikTok, but I’ll tease out two relevant points.

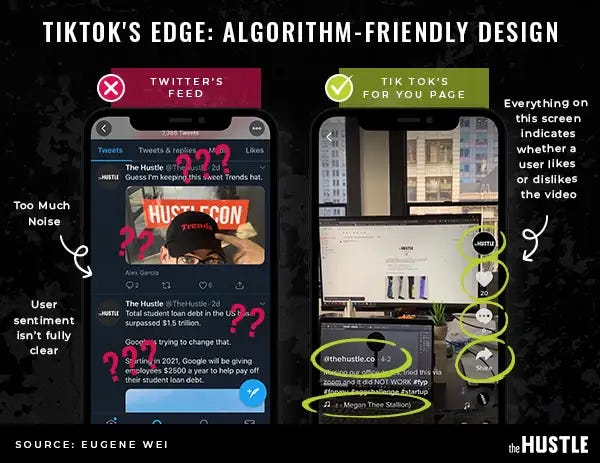

First, Wei writes that TikTok has an “algorithm-friendly design”, which allows the app to quickly figure out — and then recommend — the exact type of content a user likes. Here’s a summary I wrote for The Hustle:

TikTok’s actual machine learning (ML) recommendation algorithm is not out of the ordinary.

However, the data inputs into TikTok’s algorithm are differentiated and — all things equal — better data inputs create better algorithms.

To get the most valuable inputs possible for its algorithm, TikTok’s design is very unique: It is only one video at a time with a number of indicators as to whether or not the user likes it (length of viewing, re-watches, likes, comments, song choice, video subject, shares).

Typically, UX design is meant to be user-friendly. However, to improve its algorithm, TikTok has made its product a bit less user-friendly (users scrolling through multiple pieces of content like X/Twitter is a lower-friction experience to see as much content as possible than the single-video view that TikTok affords).

Eugene calls the product decision to have a single-video an “algorithm-friendly” design.

Compare this with a traditional social feed (X/Twitter, Facebook), both of which offer an endless scroll of content. The user inputs are less clear (“liking” something doesn’t transmit precise information).

With such clear signals — whether positive or negative — TikTok can quickly understand a user’s preference and serve up more similar content on the For Your Page (FYP) feed.

The design creates a tight feedback loop and kicks off the flywheel that continually improves TikTok’s recommendations and data inputs.

Relatedly, TikTok has very easy-to-use creator features. Not to mention the existence of CapCut, a very powerful short video editing tool also owned by ByteDance. Combined, these lower the barrier to entry for video creators.

The resulting feedback loop from creator to viewer is a steady stream of content — in 15 to 60 second hits — that dishes out that sweet sweet dopamine and keeps users engaged. The speed and consistency of delivering these dopamine hits is probably contributing to shorter attention spans, too (TikTok is training your brain to get a faster payoff than any other social app).

It’s such an effective design that TikTok’s own internal documents have quantified how many videos it takes for a user to get hooked on the app. The figure is 260 videos. We know this because the state of Kentucky is currently suing TikTok for causing mental harm to teenagers and investigators allege that “in under 35 minutes, an average user is likely to become addicted to the platform”.

Even if this statement is a touch hyperbolic, TikTok knows it has an engagement monster on its hands. The other social players — Instagram, X/Twitter, Snap, YouTube — have gotten hip to TikTok’s edge and integrated the single-view short video format into their apps.

These social media apps fight for our attention in the same way that food giants such as PepsiCo design snacks to win “share of stomach” (an actual corporate phrase).

Remember how Doritos were perfectly designed to keep you munching? Short-form videos have all the ingredients to keep you watching. Do you know how many lifetimes someone in the 1400s would have to live to experience the flavour in a single Doritos chip? The same amount of lifetimes it would take for them to experiences the number of faces, dances, graphics, songs and special FX that someone sees in a single night of TikTok-ing?

As with gas chromatography, user analytics and recommendation algorithms aren’t inherently “good” or “bad”. They are tools. Judgement can only be passed on the end product that these tools are used for and Doritos — whether in snack or digital media form — have obvious downsides.

To stretch the food-media analogy to its limit, we have to talk about the most successful digital creator in the world: MrBeast (aka Jimmy Donaldson).

Last month, a memo was leaked titled “How To Succeed at MrBeast Productions” and it went super viral in the tech and media world.

For the uninitiated — and there aren’t that many of you left — MrBeast is the world’s most popular YouTuber, with nearly 400 million subscribers across his YouTube channels.

MrBeast built the audience by crafting the perfect unit of content for YouTube. His videos fall into a few buckets: challenges, giveaways, charitable etc. (side note: MrBeast has faced some criticism for how he films these videos).

The leaked 36-page document is the distilled knowledge of MrBeast, who says he’s spent 30,000 hours studying YouTube. It’s well worth the read and covers two main themes. First, he goes deep into his management style including tips on how to find and empower top talent as well as structuring a company that has a bias for action. Second, he explains the method of creating a viral YouTube video. Not just any video. Specifically, a YouTube video. MrBeast believes YouTube will eat all media in the future and that old Hollywood type skills are less applicable.

Using YouTube analytics, MrBeast focuses on three metrics including Click Thru Rate (CTR), Average View Duration (AVD), and Average View Percentage (AVP). The metrics — which are the digital equivalent of gas chromatography for understanding how YouTube garners attention — informs his creative process for making viral hits:

“I Spent 50 Hours In My Front Yard” is [a lame title] and you wouldn’t click it. But you would hypothetically click “I Spent 50 Hours In Ketchup”. Both are relatively similar in time/effort but the ketchup one is easily 100x more viral. An image of someone sitting in ketchup in a bathtub is exponentially more interesting than someone sitting in their front yard.

I’ve spent at least 7 minutes every day over the past month thinking about a tub of ketchup since reading this PDF (and am shocked that Heinz hasn’t jumped on some partnership).

Anyway, here is a copywriting 101 tip from MrBeast:

Titles are equally as important for getting someone to click. A simple way to up that CTR even more would be to title it “I Survived” instead of “I Spent”. That would add more intrigue and make it feel more extreme. In general the more extreme the better. “I Don’t Like Bananas” won’t perform the same as “Bananas Are The Worst Food On Earth”.

Conveniently for this article, there is also an interesting missive on Doritos and how constraints breed creativity:

People always assume money is the answer and if we just spend more money we can give Jimmy what he wants. Which is wrong, creativity is the answer. Here is an example I use all the time with our gaming team. They love to give away money every video. But. Which sounds cooler to you as a prize for a gaming video. $20,000 or a year’s supply of doritos? To me doritos is so much funnier and I think our audience would find it fucken hilarious.

So lets say we define a year’s supply of doritos by 5 packs of doritos a day for 365 days. That’s 1,825 packs of doritos and a quick google search shows you can buy a pack of doritos for less than a dollar but we can round up and just say a dollar per a pack of doritos. Our prize for the video just went from $20,000 down to $1,825 because we didn’t just throw money at the problem and we used creativity.

Finally, MrBeast drops insane alpha explaining the importance of every single minute of his videos (which are 14 minutes on average):

1st Minute: Obviously, the most important to hook a viewer (good lighting is crucial for this segment).

Minutes 1 to 3: This part is a “transition from hype to execution” (it must show a lot of progress in the storyline such as time lapsing).

Minute 3: Re-engagement (content that is “highly interested that fits the story and makes people genuinely impressed”; usually a spectacle that takes a lot of time and money to produce).

Minutes 3 to 6: Plan out “the most important and exciting content that is also very simple” (quick scene changes that are highly stimulating).

Minute 6 (and the second-half of the video): Another re-engagement at this point (any viewer that makes it this far is “super invested in the story” and will probably finish watching to see the payoff).

Can you think back to that gas chromatography graph from the previous section that dissected the chemical compounds in vanilla?

In the food-media analogy, MrBeast has a similar visual for audience retention. He shows four graphs that track how many viewers stay engaged throughout a video and has notes for every spike and dip in the viewing metric:

The problem with a formula is that it can be copied. Particularly if the formula is capitalizing on the lizard-brain portion of a viewers brain (sex, action, faster, louder, quick cuts). There have been so many MrBeast clones and the appetite for his videos have shifted.

MrBeast is aware of this and has changed up his approach.

“This past year I’ve slowed down our videos,” MrBeast posted on X in March. “[I] focused on story telling, let scenes breathe, yelled less, more personality, longer videos, etc. And our views have skyrocketed! My fellow YouTubers lets get rid of the ultra fast paced/overstimulated era of content.”

There’s a whole conversation to be had about the type of content to consume (eg. fiction, non-fiction, classics, technical, poems etc.) but let’s focus more on Marshall McLuhan’s iconic idea that the “medium is the message”.

The media format we choose to consume the content shapes our mind as much as the content itself. Compare short-form video attention hacking with the experience of sitting down and getting lost in a book. During a deep reading sessions, the mind is able to imagine, make new connections, empathize, learn and contemplate. Long-form podcasts can accomplish the same thing. YouTube is an incredible education machine when used properly and a well-curated X/Twitter feed — which I share as many gems as possible in this newsletter — provides insights from top experts in nearly every field.

Ultra fast-paced videos allow for very little contemplation and learning. So, MrBeast pivoting his content away from pure overstimulation makes sense. I’ve watched — and enjoyed — many older MrBeast videos, just as I’ve really really enjoyed Ketchup-flavoured Doritos. But I wouldn’t want those to be my entire food and media diet.

The Mismatch Theory and What We Can Do

One of the most-talked about books in 2024 has been Jonathan Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation”. Haidt is a well-known social psychologist and the book posits that smartphone usage is causing a mental health crisis among teens.

The iPhone came out in 2007 and it introduced the front-facing “selfie” cam in 2010. In the following decade, usage of the social media apps exploded, coinciding with increased rates of teenage anxiety, depression, ADHD and diagnoses of other mental ailments. Haidt believes there should be tougher age restrictions on smartphones, particularly in school environments.

Obviously, correlation doesn’t equal causation and there has been pushback on Haidt’s thesis.1 But I find his book very credible and don’t plan on giving my kid a smartphone until he is 16 (relatedly: I don’t let my kid watch CocoMelon).

I say this as someone who is semi-addicted to his smartphone and created a life where I spend 5+ hours a day on various social apps “as part of my job”. To be honest, it has a negative effect on my time management and focus-levels. In a recent article, my friend Adam Singer makes a strong case for dropping Instagram and TikTok entirely:

It’s so bad I really think all you need to do is not use them, particularly on mobile, and you’ll immediately possess a level of attention/focus (and likely values) higher than a non-trivial percentage of the population. Free alpha to simply delete.

If the challenge of contemporary existence is learning how to wield attention meaningfully, then TikTok and Instagram are weapons-grade distractions, optimized by some of the smartest people given incredible monetary incentives (generational wealth in many cases) to control the human mind.

For real though, the human mind wasn’t meant to deal with “weapons-grade distraction” non-stop throughout the day. It’s not just the social media apps. It’s streaming services, video games, messaging, sports-betting platforms, dating apps and online investing tools. They are all designed to capture our finite attention and all are available in our pockets, at the tap of a button. Ted Gioia refers to these apps as the “rise of dopamine culture”.

Harvard evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman has a concept called “mismatch theory”, which states that a lot of modern-day illnesses are caused by the fact that our bodies were designed for a different environment.

The human body isn’t optimized for the modern lifestyle of sitting at desks all day with easy access to (ultra-processed) calories. Our early evolutionary ancestors walked or ran 10km a day and were frequently in states of caloric deficits as Lieberman explained on the Plain English podcast:

“We are mismatched. We are dis-evolved for our modern world. To take one quick but illustrative example, you and I are built for an environment to crave sugar and efficiently store energy as fat, for a world where sugar and fat are scarce.

And until very recently, they were. Before World War I, the average American ate half an ounce of fructose per day. Today, he or she consumes more than two ounces, a quadrupling of daily sugar intake, in just one century.

Our food systems are progressing at the warp speed of technology while our bodies evolve at the languid speed of evolution. And the price of this mismatch is all around us. Insurgent obesity and widespread cardiovascular disease and more cavities in our teeth and more cancer in our bodies.”

It doesn’t take much imagination to see how Lieberman’s “mismatch theory” applies to smartphones and social media. Here are some evolutionary adaptations and how they are mismatched with the smartphone media landscape:

Social group sizes: Humans are adapted to navigate small groups with the Dunbar Number stating that we have the cognitive capacity to sustain about 150 relationships

Present-Day Mismatch: It’s easy to create “connections” on social but if you’re spending all your time developing 100s of shallow relationships vs. 10s of deep relationships, you won’t get the psychological benefit of true friendship.

In-group favoritism: These small groups increased the odds of survival by co-operating with familiar people as opposed to strangers.

Present-Day Mismatch: On social media, our tribal instinct to favour an “in-group” is constantly being triggered whether it is for sports, politics, fandom, race or ethnicity; the evolutionary adaptation for in-group favoritism clearly has a purpose but having it constantly activated is not great for the psyche.

Social Pressure: Group cohesion and survival also led to the development of emotions including shame (promotes adherence to social norms), guilt (encourages people to make amends), disgust (reinforces cultural taboos), anger (mobilizes resources), pride (highlights valuable achievements) and envy (motivates self-improvement).

Present-Day Mismatch: Again, these emotions serve a purpose but we aren’t adapted to having them constantly triggered, which is what happens while scrolling social media for hours on end (especially, if you constantly get into random online beefs).

Hyper-Vigilance for Danger: Early survival also meant that we were constantly in threat-detection mode, which activates the stress-inducing fight-or-flight mode.

Present-Day Mismatch: Social media — like all media before it — lives by the aphorism of “if it bleeds, it leads”, meaning rage, sex, violence and tragedy attract the most attention. The engagement that this type of content generates feeds back into the algorithm, which gives us more of it and the loop never ends.

In sum: our psychological make-up isn’t meant to deal with a daily routine that is non-stop dopamine triggers, constant comparisons, status games, FOMO, cyberbullying, attention fragmentation, information overlaid, and pressure to be available.

As Harvard sociobiologist E.O. Wilson’s famously said, “The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Palaeolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall.”

The backlash to ultra-processed media is still in the early days but I can totally see people in the 2050s looking back at the 2010s and viewing our smartphone and social media habits as comparable to how we currently look at smokers from the 1970s and 1980s.

In terms of technological progress, I can’t actually decide if this attitude change is bullish or bearish for the tech industry’s dreams of augmented reality (AR) glasses. I get that AR eyewear can hypothetically make you “more present” as compared to staring at your smartphone. But do we actually need something that is directly in our field of vision creating a digital overlays and sending us notifications? What about AI-powered friends and companions? Is this the ideal future?2

Obviously, we’re not going back to a pre-industrial food supply or a pre-smartphone attention hacking era. Food abundance had to happen. Meanwhile, there are huge benefits to having instant connection, access to all human knowledge and boundless types of entertainment options.

But the mismatch is obvious.

Thankfully, the solutions are also obvious. While we invented “going to the gym” and “running on a treadmill” over the past 50 years to help deal with overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, cleaning up our media diets is more straightforward.

Spend less time on social media. Put the smartphone away (or use a Kale Phone and a Cocaine Phone). Read a book. Walk outside. Play some sports. Touch some grass. Hit a quick meditation sesh. Hang out with a friends and family IRL. Go to a live music show and enjoy the vibes with other fans. Milk 10,000 cows. Make some home-made real vanilla extract.

I’m not saying we need to become peasants from the 1400s, but we could all do with a bit less extreme nacho flavour — whether in a triangle corn shape or a rectangular black mirror shape — in our lives.

Links and Memes

Temu vs. Amazon: Temu is an online marketplace that sells really cheap stuff, mostly from Chinese manufacturers. It is owned by Chinese Pinduoduo, a $170B online retailer.

You may have seen Temu during the Super Bowl with the tagline “Shop like a billionaire” (hilarious). Temu has built a pretty larger business in America by spending billions on Facebook ads and exploiting a regulatory hack called the “de minimis loophole”, which allows shipments under $800 to face very light customs scrutiny (Chinese clothing giant Shein also exploits this loophole).

The US government is rolling out legislation to “curb the abuse” of this loophole, but Temu and Shein have been so successful that Amazon has been forced to respond. Since so many Amazon merchants are from China, Temu has been poaching them by offering lower listing fees on the Temu platform. So, Amazon just announced the launch of a low-price storefront including $8 jewlery and $13 guitars (we can all swag out like billionaires now).

I tell you all this because I was on Reddit and discovered a wild arbitrage hack between Amazon and Temu. It is from the "r/UnEthicalLifeProTip” subreddit, so maybe don’t try it:

Find something on Temu but want it the next day? Order on Amazon and Temu!

Just did this. Same seller for some storage equipment for an event. $90 on Amazon, $16 on Temu.

Ordered on both websites. Amazon arrived next day, Temu arrived 3 weeks after the event. Returned the Temu purchase on Amazon. It was exactly the same item from the SAME Chinese seller. Insta refund on Amazon.

Amazon does throttle people that abuse the free refunds and I’m sure they will find a way to punish merchants doing double listings. But this is such a classic example of “show me the incentive, I’ll show you the outcome”. These Redditors literally invented Temu Prime.

***

Intel almost bought Nvidia….in 2005. At the time, Intel was worth ~$100B and was mulling a $20B offer for Nvidia. The board said no. Today, Intel is still worth ~$100B while Nvidia is up 175x to a ludicrous $3.5T. Honestly, Intel’s corporate politics would have destroyed Nvidia and it’s unlikely Jensen Huang — and his baller leather jackets — would have hung around to build the beast that he did, especially since Intel wasn’t giving him the CEO seat. A great tech history Sliding Doors moment. (New York Times)

***

AI Agents Are Here?: Anthropic released a tool called “Computer Use” that can take over your computer and use it like you would (move the mouse cursor, open browsers, download files, use coding to tools). Hilariously, it also learned the art of procrastination with one example showing the agent taking a break from coding and searching for photos of Yellowstone National Park. That’s as human as it gets.

Anyway, Wharton Professor Ethan Mollick has a good write-up on his early impressions of the tool, which he used to create a lesson plan for the book “The Great Gatsby”. He says the lesson plan was decently well-done but a larger takeaway was that the AI agent “presented finished drafts to comment on, not a process to manage…I simply delegated a complex task and walked away from my computer, checking back later to see what it did” a few hours later. (One Useful Thing)

***

An MMA fighter from Tajikistan flew to America for a UFC presser and — in broken English — asked UFC owner Dana White to give him a chance to fight. White was a bit taken a back but then agreed. A “hall of fame shoot-your-shot” move. (X post)

…and them fire posts:

Finally, Apple had a meh week. The company will reportedly discontinue producing the first version of the Apple Vision Pro and focus on a cheaper model. Meanwhile, the expected rollout of Apple Intelligence sounds underwhelming (basically a slightly improved Siri with some notification summary features).

Apple CEO Tim Cook has said that Apple’s approach is “not first, but best”. With over 2 billion iPhones floating around, Apple will certainly have one of the biggest distribution footprints (only Google really compares) and most people will probably have their first real “generative AI” experience with Apple.

The iPhone notification summary is apparently quite useful for backlogged notifications (eg. reminder to tip Uber drivers, smart home device pings, Amazon package delivery updates) but the the iMessage summaries can be overly robotic and I collected a bunch of hysterical examples in this thread:

Haidt went on economist Tyler Cowen’s podcast and Cowen had some strong rebuttals: 1) the younger generation will eventually figure out how to benefit from social media — particularly for making connections — while limiting the downsides; 2) the smartphone-induced mental health crisis seems relegated to “Anglosphere and Nordic countries”; 3) and people over 50 spend 5+ hours a day watching cable TV and that doesn’t seem great for their psyche, either.

Generative AI will profoundly change how we view social apps. Some of the apps that have garnered the most engagement from this recent AI wave are chatbots. Users spend hours a day on them speaking with AI characters. One story from last week was particularly salient (and sad). A 14-year old boy from Florida killed himself after chatting with a Game of Thrones character (Daenerys Targaryen) from the AI chat app Character.AI.

The boy’s mom is suing Character AI and produced transcripts to show that the AI bot may have pushed the boy to suicide from an exchange that didn’t fully grasp his euphemisms.

Three notable discussions I’ve seen from this story: 1) did Character AI provide enough guardrails in its AI model to ensure certain conversations were out of bounds?; 2) the boy had access to his father’s gun which brought up the broader question of firearm safety and the parents’ responsibility for keeping a safe home; and 3) a lot of Character AI users have come out and said that the app has been very important for their own mental health, with the AI bots helping them deal with issues that real humans may not have the time to hear (or not want to hear and tell them that they are “trauma dumping”).

What a banger. Love the writing style, milk 10000 cows… do not, I repeat DO NOT… Mind exploding.

Eases in to a serious topic. Also super insightful with regards to the food industry, didn’t know that a) cola is designed to not taste like one specific flavor and b) to avoid one getting tired of it.

Thanks man.

Excellent article