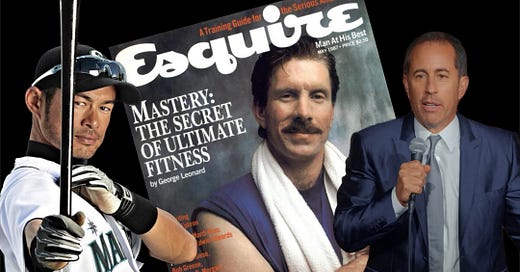

Jerry Seinfeld, Ichiro Suzuki and the Pursuit of Mastery

Notes from the 1987 Esquire magazine issue that inspired Jerry Seinfeld to "pursue mastery [because] that will fulfill your life".

Hey, thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about how Jerry Seinfeld and Ichiro Suzuki have dedicated their lives to mastering a skill (comedy, baseball).

Also this week:

Netflix’s Password Crackdown Worked

Red Lobster’s Bankruptcy

…and them fire memes (including Chipotle)

Jerry Seinfeld is 70 years old.

He recently made his directorial debut with the film Unfrosted, a fictional re-telling of the origin of the Pop Tart (which ranks up there with a jar of Nutella as one of the most ridiculous food products that humans once thought was appropriate to eat as part of a nutritious breakfast).

From 1989 to 1998, Seinfeld made a fortune by creating his eponymous sitcom and has maintained an impressive work pace in the decades since (including touring for stand-up and the show Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee).

Last month, Seinfeld hit the interview circuit to promote Unfrosted. During one interview, The New Yorker’s editor David Remnick asked him why he keeps grinding after all these years and Seinfeld’s answer was glorious:

David Remnick: It is possible that you've probably made a dollar or two from Seinfeld, and yet you still work so hard. Why?

Jerry Seinfeld: Because the only thing in life that's really worth having is good skill. Good skill is the greatest possession. The things that money buys are fine. They're good. I like them. But having a skill [is the most important thing].

I learned this from reading Esquire magazine. They did an issue on ‘mastery’…a very zen Buddhist concept.

Pursue mastery that will fulfill your life. You will feel good. I know a lot of rich people and they don't feel good as you think they…would. They don't. They're miserable. So I work because if you don't in standup comedy — if you don't do it a lot — you stink.”

Seinfeld has talked a lot about his creative process in recent years but I had never heard him directly mention Esquire magazine.

So I went looking for that issue of Esquire. Seinfeld said he read it in the 1960s but I could’t track anything down. However, in May 1987 — two years before the TV show Seinfeld premiered on NBC — Esquire published an issue titled “Mastery: The Secret of Ultimate Fitness” with Philadelphia Phillies third-base legend Mike Schmidt on the cover.

At the time, Seinfeld was a successful 33-year old stand-up comedian with over a decade of experience. My guess is that Seinfeld meant to say he started reading Esquire in the 60s — when he was still only 6 to 16 years old — but the actual “Mastery” issue wasn’t until later. The 1987 Esquire issue I found clearly didn’t lead Seinfeld down the path of comedic perfection, but I think it gave him the vocabulary and frameworks to describe his intense work ethic.

The Esquire issue on “Mastery” centers around athletics. Mastery is obviously possible in all types of fields — writing, cooking, negotiating, composing, acting etc — but sports are the most recognizable and relatable path for many people. I’m guessing that most of you readers have spent at least 100 hours on a single athletic pursuit in your life. You may not be a professional but you are trying to get better and on the path of mastery (raise your hand if you have a slick Beer Pong stroke).

To be sure, there have been notable works in recent decades on the topic of mastery, including Robert Greene’s Mastery (2012) and Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers (2008), which popularized the “10, 000 Hour Rule” (people have debunked the “10,000 hour rule” to say that everyone takes a different amount of time to achieve mastery but I think most readers get the gist: if you engage in dedicated practice for one skill for a long time, there will be results).

And while the Esquire issue on mastery is a bit older than those books, it still has gem insights and I love digging into sources of inspiration that have inspired the people who inspire me (in this case: Seinfeld).

These are my key takeaways from Esquire’s “Mastery” issue:

Anyone Can Pursue Mastery

Mastery is Plateaus and Brief Spurts of Progress

Mastery is a Lifelong Journey

The Importance of a Child’s Mindset

Mastery & Muscle Memory

The Zen Buddhism Connection

4 Traits Shared By Practitioners of Mastery

Anyone Can Pursue Mastery

The main article on this topic is titled “Playing For Keeps: The Art of Mastery in Sports and Life” (find on page 113 in a PDF of the issue I uploaded here). Edited by George Leonard, the first three paragraphs of the piece go very hard:

“It resists definition, yet can be instantly recognized. It comes in many vanities, yet follows certain unchanging laws. It makes us in the words of the Olympic motto, ‘Faster, higher, and stronger,’ yet is not really a goal or a destination but rather a process, a journey.

We call this journey mastery and tend to assume that it requires a special ticket available only to those born with exceptional abilities. But mastery is not reserved for the super talented or even for those who are fortunate enough to have gotten an early start. It is available to anyone who is willing to get on the path and stay on it — regardless of age, sex, or experience.

The problem is that we have few, if any, maps to guide us on the journey or even show us how to find the path. The modern world can be viewed as a prodigious conspiracy against mastery. We are bombarded with promises of fast, temporary relief, immediate gratification, and instant success, all of which lead in exactly the wrong direction.”

The Esquire issue must have really stood out at the time because best practices in athletics— training, nutrition, rest, mindfulness etc. — were a joke compared to now. During the 1980s, professionals in the NHL, NFL, MLB and NBA still flew commercial and regularly drank alcohol and ate junk food during the season.

Having said that, the last paragraph — specifically the line “The modern world can be viewed as a prodigious conspiracy against mastery” — is as relevant as ever. While TV was a growing distraction in the mid-80s, it was nothing compared to the smartphones in our pockets. However, it should also be noted that the distractions available to us are now offset by the rise in self-guided learning tools such as YouTube, which I believe will have a comparable impact on education similar to the printing press.

***

Mastery is Plateaus and Brief Spurts of Progress

The next section talks about Leonard’s journey of learning to play tennis.

A tension he has to deal with is the desire to get instant results, while his tennis instructor tells him to stay patient. The tennis instructor doesn’t even want a student to play against another opponent for at least 6 months. Instead, the two will spend their training time perfecting the grip.

The instructor is trying to impart two main lessons:

“Learning something new involves relatively brief spurts of progress, each of which is followed by a slight decline to a plateau somewhat higher than what preceded it.”

“You must be willing to spend most of your time on a plateau to keep practicing even when you seem to be getting nowhere.”

In fact, Leonard writes that learning to embrace plateaus may be the key ingredient for mastery:

“The most important lessons here — especially for young people — is that even if you’re shooting for the stars, you’re going to spend most of your time on a plateau. That’s where the deepest, most lasting learning takes place, so you might as well enjoy it. When I was first learning…I just assumed that I would steadily improve.

My first plateau was something of a shock and disappointment, but I persevered and finally experienced an apparent spurt of learning. The next time my outward progress stopped, I said to myself ‘oh damn, another plateau’. After a few months, there was another spurt of progress and then, of course, the inevitable plateau. This time, something marvellous happened. I found myself thinking ‘Oh boy, another plateau. Good, if I stay on it and keep practicing, I’m absolutely assured another surge of progress. It was one of the best and warmest moments of my life.’”

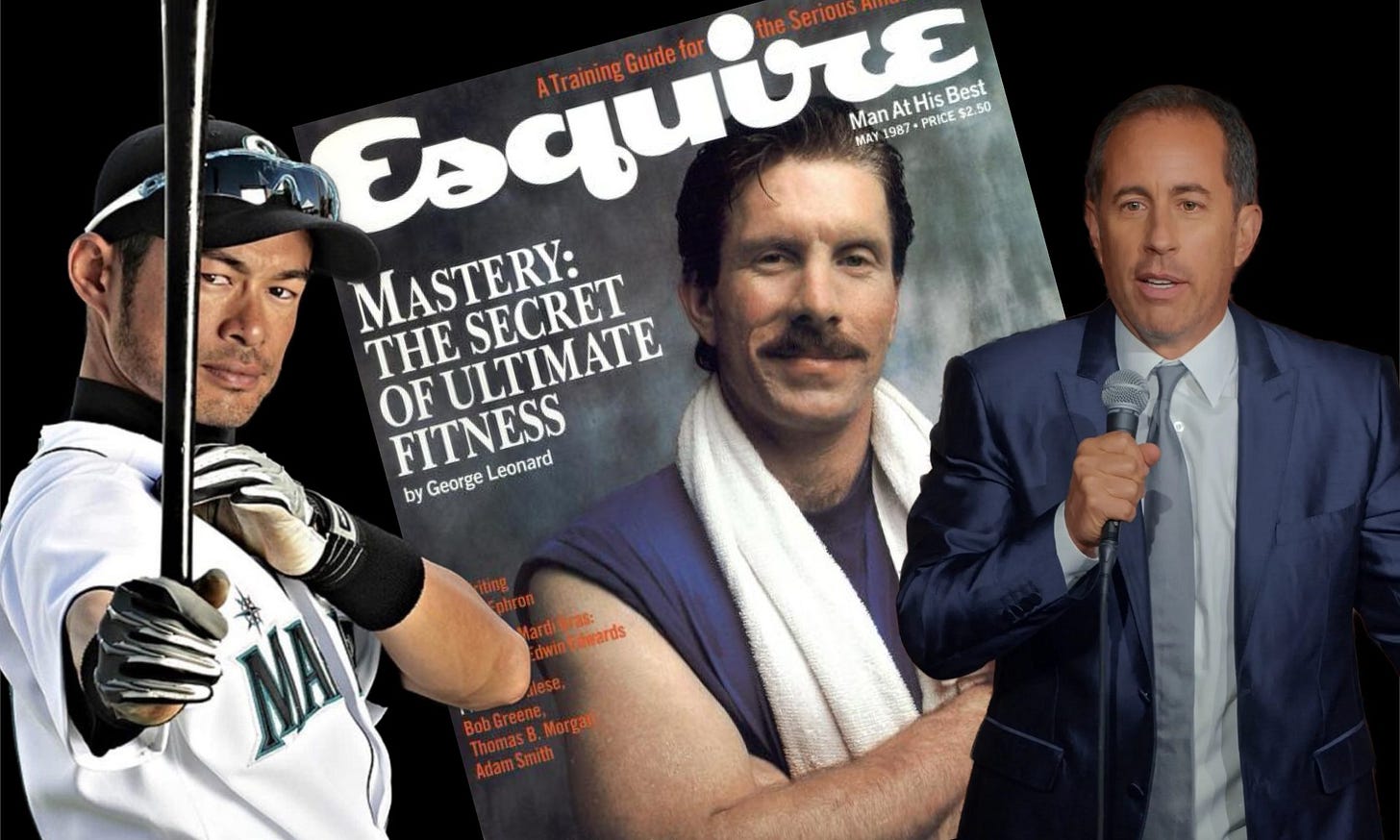

Below is an image of the mastery journey that includes “brief spurts of progress” and “spending most of your time on a plateau”.

Esquire contrasts this ideal version of the mastery journey with three sub-optimal paths (each with an accompanying visual):

The Dabbler: “The Dabbler approaches his new sport with great enthusiasm. He announces proudly to everyone he knows that he is going to take up tennis, golf, martial arts, bodybuilding, running, swimming, whatever. He loves the shiny new equipment [and] the spiffy training suits. When he makes his first spurt of progress, his enthusiasm knows no bounds. He demonstrates his form to family, friends and people he meets on the street. He can’t wait for the next lesson.

The falloff from his first peak comes as a shock. The plateau that follows is incomprehensible. His enthusiasm quickly wanes. He starts missing lessons. His mind fills up with rationalizations. This really isn’t the right sport for him. It’s too competitive, non-competitive, aggressive, nonaggressive, boring, dangerous, whatever. He tells everyone that it just doesn’t fulfill his unique needs. Starting another sport gives the dabbler a chance to replace the whole scenario. Maybe I’ll make it to the second plateau this time, maybe not. Then it’s on to something else.”

The Obsessive: “The Obsessive is a bottom-line kind of guy. Not one to settle for second best. He knows results are what count and it doesn’t matter how you get them, just so you get them fast. In fact, he wants to get the stroke just right on the very first lesson. He stays after class talking to the instructor. He asks what books and tapes he can buy to help him make progress faster. He leans toward the listener when he talks…his energy is apparent when he walks. The Obsessive starts out by making robust progress. His first spurt is just what he expected. But when he retrogresses and finds himself on a plateau, he simply won’t accept it. He redoubles his effort. He pushes himself mercilessly. He refuses to accept his instructor’s counsel on patience and moderation. Somehow, he manages to keep making brief spurts of progress followed by sharp declines — a jagged roller coaster ride toward a sure fall. When the Obsessive is finally forced to quit, it’s quite often due to an injury.”

The Hacker: “The Hacker has a different attitude. After he sort of gets the hang of a sport, he is willing to stay on the plateau. He doesn’t mind skipping stages essential to development of a master player if he can just go out and hack around with the fellow hackers. If it is golf, he gets locked into an eccentric but adequate swing and is satisfied with it. If it is tennis, he develops a solid forehand and figures he can make do with his backhand. If it’s martial arts, he likes the power but not the endless discipline. His idiosyncrasies become his game. He shoots in the low nineties on the links, spends most of his time on the court working around his weaknesses and wears a martial arts brown belt until it’s faded and frayed. He’s a good guy to have around but he’s not on the journey of mastery.”

Man, these sub-optimal archetypes hit home. While I was reading this section, I kept thinking “bro, just @ me”. Although I never went into “obsessive” mode, I did a lot of “dabbling” and “hacking” in my teens and 20s trying to improve at billiards, swimming and hoops. Looking back, the skill plateaus definitely dissuaded me from going further.

***

Mastery is a Lifelong Journey

As you get older, I think it is totally fine to “dabble” and “hack” (especially to avoid injury), but having at least one pursuit that you take seriously is probably a good idea. As everything changes — work, family, social networks, locations — having a lifelong pursuit helps ground your day-to-day routine:

“If you stay on it long enough, you’ll discover that the path is a vivid place, with its ups and downs, its challenges, comforts, its surprises, its disappointments, and unconditional joys. You’ll take your share of bumps and bruises while travelling it — bruises of the body and of the ego. The path could turn out to be the most certain and reliable thing in your life, always there for you when everything else is falling apart. It will give you plenty of exercise, a well-tone body, a feeling of self-confidence and an added charge of energy for your career and your good work. Eventually, it might well make you a winner in your chosen sport, if that’s what you’re looking for and then people will refer to you as a master. But that’s not really the point: What is mastery? At the heart of it, mastery is staying on the path.”

***

The Importance of a Child’s Mindset

Starting on the path of mastery requires qualities that are more commonly found in children than in adults — curiosity, being present, and lack of ego (specifically, not caring if you fail):

“[The reason many adults are unable to learn new skills] is because they have allowed themselves to fall prey to that old archenemy of mastery: excessive goal orientation. The typical adult in our culture, as I’ve suggested before, is constantly looking ahead. Is impatient for significant results and is unwilling to appear foolish or to make mistakes. The typical young person, on the other hand, is more sensuous, more in the moment and less concerned about appearances or results.

In any case, age isn’t the most important variable in the equation of mastery. Attitude is. If you’re in fairly good shape and are willing to approach a sport with a child’s openness and sense of wonder along with a determination to stay on the path, you can start at any age.”

***

Mastery & Muscle Memory

One of the paradoxes of mastery is how the best athletes in a sport usually make it look effortless (think Roger Federer in tennis or Steph Curry in basketball). Of course, it looks effortless because of the countless hours of practice. The physical movements becomes “muscle memory” and the actions are on “autopilot”.

There has been significantly more research on the topic since the mid-1980s but it’s interesting to read what Seinfeld read all these decades ago:

“The brain-body mechanism through which this takes place is still a matter of some controversy, but it probably matches up fairly well with these informal descriptions (e.g. “autopilot”). Karl Priban, professor of neuroscience and pioneering brain researcher at Stanford University, explains it in terms of a Habitual Behaviour System that operates at a level deeper than thought.

The Habitual System involves the reflex circuit in the spinal cord as well as in various parts of the brain to which it is connected. It makes it possible for you to do things — jump over a hurdle or return a scorching tennis serve — without worrying just how you do them. When you start to learn a new skill, however, you do have to think about it and you have to make an effort to replace old patterns of sensing and movement with new ones.

That brings into play what may be called a cognitive system associated with the Habitual System and an effort system, associated with the hippocampus (situated at the base of the brain). The cognitive and effort systems become subsets of the Habitual System, long enough to modify it and teach it new behaviour. To put it another way, the cognitive and effort systems click into the Habitual System and reprogram it. When the job is done, the systems withdraw. Then you don’t have to stop and think about the right grip every time you shift your racket.”

***

The Zen Buddhism Connection

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance is the best-selling philosophy book in US history. It was written by Robert Pirsig and first published in 1974. There is a 97% probability that you bought a copy in your early-20s as something to read during a backpacking adventure and only ever finished the first 9 pages.

The book is often credited for helping to popularize Zen Buddhism in America and was itself inspired by Zen In the Art of Archery, a German text published in 1948, which was referenced in the Esquire piece:

“In recent years, a growing number of Westerners have been fascinated by accounts of Eastern masters who offer their students years and years of goal-less practice. In the book ‘Zen In The Art of Archery’, for example, a goal-oriented German philosopher named Eugene Herngel tells of spending a whole year under a Japanese master’s tutelage just learning how to breathe correctly while drawing the bow and then spending the next four years learning to loose the arrow — without once trying to hit the target.

There’s a paradox here. One who renounces immediate goals for the sake of diligent practice generally ends up reaching higher goals than one who shoots for quick results. One who takes the path of mastery is likely to end up a winner more often than one who thinks about nothing but scoring points. But winning for a true master isn’t something to use as fuel for a depleted ego or to gloat about with cries of ‘number one’. It’s simply part of a process that began long ago that will continue as long as life goes on.”

This isn’t directly related to Zen Buddhism, but Seinfeld is famously known for his transcendental meditation routine. He meditates twice a day for 10 to 20 minutes a session. In an interview with Graham Besinger during the Unfrosted press tour, Seinfeld explained why carving out time for meditation is important:

“I'd like to make the most of my ability and be happy. What does it take to do that? Energy. You need need energy. It's the most valuable quantity of human life. […]

Meditation is effortless exercise…Exercise is great for energy but it takes more effort…Meditation is like if I said to you ‘I'm going to need you to get in a hot tub once a day and just sit there for five minutes’. Could you do that? That's pretty easy. It's pretty easy. Meditation is even easier than that. [It helps you] double the amount of energy that you have to accomplish what you want to accomplish. […]

If you ask me my three keys to a successful life…[it is] transcendental meditation, lift weights [and drink] espresso. Just do those three things and you will kill it.”

***

4 Traits Shared By Practitioners of Mastery

The Esquire issue concludes with 4 commonalities among people who pursue mastery:

Enthusiasm: “Whether it’s in a sport or an art or some other work, those we call masters are shamelessly enthusiastic about their calling. Like everyone else, they might at times complain, but they actually can’t imagine anything else they’d rather be doing. This helps account for the unusually long hours they put in. It works both ways. Having a great deal of experience at something worthwhile makes you enjoy working at it. Enjoying what you work at results in your wanting to get more experience.”

Generosity: “The word ‘generous’ comes from the same root as ‘general’, ‘generative’ and ‘genius’. Some of those known as geniuses might be selfish, vulgar, cruel, and generally obnoxious in other aspects of their life (witness the lives of some of our musical geniuses), but insofar as their own particular calling is concerned, they have a remarkable ability to give everything and hold nothing back. Perhaps, in fact, genius itself can be defined in terms of giving-ness.”

Zonshin: “This wonderful Japanese word translates roughly as ‘unbroken concentration’ or ‘continuing awareness’. One who has Zonshin is alert, aware, and focussed, not just when the play is going on, but also between plays all the time. Experienced pilots can tell a lot about how good another pilot is simply by the way he or she gets into the pilot’s seat and straps on his or her safety harness. There are some people who are so obviously ‘on’ that they give us a life just by walking onto the field or into the room. We see this vividly in certain sports figures…It was said of the legendary Ben Hogan that other golf pros learned a lot about the game just by studying the way he moved down the fairway between shots. Hogan’s Zonshin — his unbroken concentration — seemed to evoke a whole world of mastery. Most of us know or have known someone like that. Someone who — through the dedicated practice and years of focused intensity — can demonstrate mastery simply by the way he or she stands.”

Playfulness: “Obsessives are dead serious, those on the path of mastery are willing to take chances and to play the fool. A high school physics teacher is likely to be more sombre about physics than Einstein. [British-American anthropologist] Ashley Montagu has written about ‘neoteny’ — a certain childlike quality that is often associated with genius…The most powerful learning is that which is most like play. A Hacker can waste energy trying to look good, since he already knows all he’s going to know. Someone on the path of mastery is so interested in new approaches and new leanings, that there’s no energy left for appearances.”

Seinfeld and Ichiro Suzuki

I haven’t mentioned much about Mike Schmidt from the cover of the Esquire "Mastery" issue. The magazine profiles the Hall-of-Fame baseball player and details his off-season workout. But the most relevant aspect of Mike Schmidt for this article is the fact that Jerry Seinfeld's favorite sport is baseball.

Why? Because his favorite player is Japanese icon Ichiro Suzuki, who may have had the most insane work ethic of any baseball player ever. At the age of 12, Ichiro decided that he wanted to become a professional player, and his father designed a training program for him to master the art of hitting.

It was extremely rigorous. Every day after school “from 3:30 to 7 p.m., Ichiro would hit soft toss and take fungo drills in a nearby park. After returning home for dinner and schoolwork, he’d work in the batting cage from 9:30 to 11.”

Ichiro did this for 360 days out of the year and set aside a total of 6 hours each year to play with friends.

He maintained some form of this routine for the next three decades until his retirement in 2019 at the age 45. Over his career, Ichiro notched a record of 4,367 hits as a professional player including 9 years in Japan and 19 years in America.

Ichiro could do everything as a player — hit, field, run bases — but his consistency is what stands out above all. During one ludicrous period of his Major League Baseball (MLB) run, Ichiro had a streak of 10 straight seasons with 200+ hits, a batting average of .300+ and a Gold Glove for his defensive play.

Mike Cameron played with Ichiro with the Seattle Mariners and said that, “What jumps out is just [Ichiro’s] consistency. His consistency and his work ethic. He calls it a word in Japanese: it's called kaizen, and in Japanese that means never-ending [or continuous improvement]. So he was never satisfied.

Seinfeld once told ABC News, “I'm obsessed with Ichiro. He's one of my favorite players. If I could be any athlete, that's the guy.”

Ichiro took a particularly extreme path to mastery. He made huge sacrifices in time and friendships. It’s not for everyone. However, some form of the path Ichiro took is available for anyone to excel in their chosen field.

“I'm not a big guy,” Ichiro — who is 5'11 and 175lbs — said while reflecting on his career. “And hopefully kids could look at me and see that I'm not muscular and not physically imposing, that I'm just a regular guy. So if somebody with a regular body can get into the record books, kids can look at that. That would make me happy.”

There are countless Ichiro anecdotes that highlight his obsession with mastering baseball at the exclusion of any other interests. My favourite is when Tom Brady texted him in 2017 for stretching tips and Ichiro ignored it because…he did not know who Tom Brady was, per Peter Gammons at The Athletic:

One morning in spring training, 2017, he was in the coaches’ room looking at his cell phone text messages. Ichiro told the coaches about one message he had just received from a number he didn’t recognize. The guy said he’d gotten Ichiro’s number from Alex Rodriguez, and that he wanted to come meet him and study his stretching system.

“What’s the guy’s name?” asked one of the coaches.

Ichiro scrolled to the end of the text. “Some guy named Tom Brady. Who the f— is Tom Brady?”

In 2012, the New York Times profiled Seinfeld as he was about to launch his new web show Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. The article has three excerpts that echo Ichiro’s story and the path of mastery:

Practice, practice, practice: Seinfeld writes everyday and is constantly drilling a stand-up set in his head (“When he scored his first appearance on Johnny Carson’s ‘Tonight Show,’ in 1981, he practiced his five-minute set ‘200 times’ beforehand, jogging around Manhattan and listening to the ‘Superman’ theme on a Walkman to amp up.”)

Consistency: Despite making $500m+ from the Seinfeld TV show from 1989 to 1998, Seinfeld never let up on his pursuit of mastery as a stand-up comedian (“[Since 2000], Seinfeld has spent a portion of nearly every week doing stand-up. He is on track to do 89 shows this year, plus private appearances, which shakes out to about two performances a week. He’s living the life of a road comic, albeit one who sells out 20,000-seat London arenas and schleps to gigs via chartered planes rather than rented subcompacts.”)

Patience: Seinfeld prioritizes quality over quantity and will workshop an idea for years. The seed for the film Unfrosted was planted by a Pop Tart joke that he spent two years workshopping. (“Seinfeld will nurse a single joke for years, amending, abridging and reworking it incrementally, to get the thing just so. ‘It’s similar to calligraphy or samurai,’ he says. ‘I want to make cricket cages. You know those Japanese cricket cages? Tiny, with the doors? That’s it for me: solitude and precision, refining a tiny thing for the sake of it.’”)

One of the reasons Seinfeld is able to approach the craft in this manner is because he considers comedy a lifelong pursuit. The highs and lows all wash away in the grand expanse of a lifetime. He controls what he can control and trusts that putting in the work every day will yield results. The effort compounds and the world gets some glorious comedy (side note: I have settled on some form of writing as the skill I want to "master" and intend to do some form of it every single day for the rest of my life).

During the NYT interview, Seinfeld said he planned to do stand-up comedy "into his 80s and beyond." It has been 13 years since then. Staying true to his word, Seinfeld is now 70 years old and still performing.

I'll finish up by flagging one more Seinfeld quote from the NYT profile:

“If I don’t do a set in two weeks, I feel [anxious about my skills]. I read an article a few years ago that said when you practice a sport a lot, you literally become a broadband: the nerve pathway in your brain contains a lot more information. As soon as you stop practicing, the pathway begins shrinking back down. Reading that changed my life. I used to wonder, Why am I doing these sets, getting on a stage? Don’t I know how to do this already? The answer is no. You must keep doing it. The broadband starts to narrow the moment you stop.”

I think we know which article he is referring to.

It has to do with mastery and he is still on that lifelong journey.

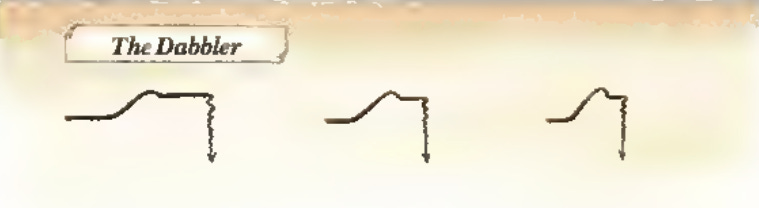

***

UPDATE: After sharing this article on X, Steward Brand informed me that George Leonard wrote a book on the topic of Mastery in 1992. I bought it on Kindle and according to the introduction, the response to the 1987 Esquire issue on Mastery was was huge. Corporate executives and athletes shared the article widely, inspiring Leonard to expand the idea into a book (here is the Amazon link).

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email.

If you press this blue button below, you can save hours of work with AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (the new GPT-4o, Claude Opus 200K) and speech-to-text transcription tools (Scribe, Whisper).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app). Use code BEARLY1 for a FREE month of the Pro Plan.

Links and Memes

Netflix’s Password Crackdown (Really) Worked: Remember when Netflix announced it was doing a crackdown on password sharing? I was uber annoyed because a Netflix password was comparable to cigarettes in prison, an asset you could barter for other assets (mostly more streaming passwords). You or someone you knew had built an elaborate Google Sheet with multiple streaming service passwords that a group of people all shared and split the cost (and then added a bunch of freeloading friends like your cousin’s boyfriend’s uncle’s high school classmate).

But then higher interest rates and a competitive streaming market changed the entire dynamic. Netflix needed everyone to pay for an account. People — including myself — hemmed and hawed about refusing to pay but it looks like Netflix got its way. The $260B streamer added 30m new paying users in 2023 (its 2nd best year ever) and another 9m in Q1 (2nd best quarter only after the start of COVID). The change was spearheaded by Greg Peters — who was previously Netflix’s CPO and is now co-CEO.

Lucas Shaw at Bloomberg has interesting details on how it all went down:

Netflix built a model to differentiate a single user travelling or one person sharing with lots of other people (**cough** me **cough**).

It then tested two methods to shake freeloaders: 1) pay per household like how the cable industry works (this was Reed Hasting’s plan); or 2) a user could access the account anywhere in the world and add new users for an additional fee (Greg Peters championed this path, which was consistent with a central Netflix tenet: “If you paid for it, you could take it with you.”)

Netflix then ran A/B tests in Latin America, where password sharing was “most widespread” (Peter’s method #2 led to more upgrades and Netflix settled on this path)

Netflix has clearly won the streaming wars. The other major players — Disney, Paramount, Max etc. — are all discovering how expensive it is to acquire and retain customers while building a massive content library. These services have announced their own password crackdowns but I don’t think they will be as successful as Netflix. Now, Netflix is looking for other revenue levers to pull including live sports, advertising and video games. Thankfully, none of these business lines will force me to have the following text conversations:

***

Chipotle is on a tear: Over the past 5 years, Chipotle's market cap has tripled from $29B to $87B (it briefly overtook Starbucks in value). One of the main reasons for this performance is the significant improvement in the Mexican Grill's operating margins, increasing from 19% to 28%.

The margin improvement is partly due to how stingy the restaurant has gotten with ingredients and I’m telling you this because comedian Andrew Rousso has one of the funniest short videos ever and it's about ordering a burrito at Chipotle (which includes asking for only the “bean water” and “carnitas liquid”).

***

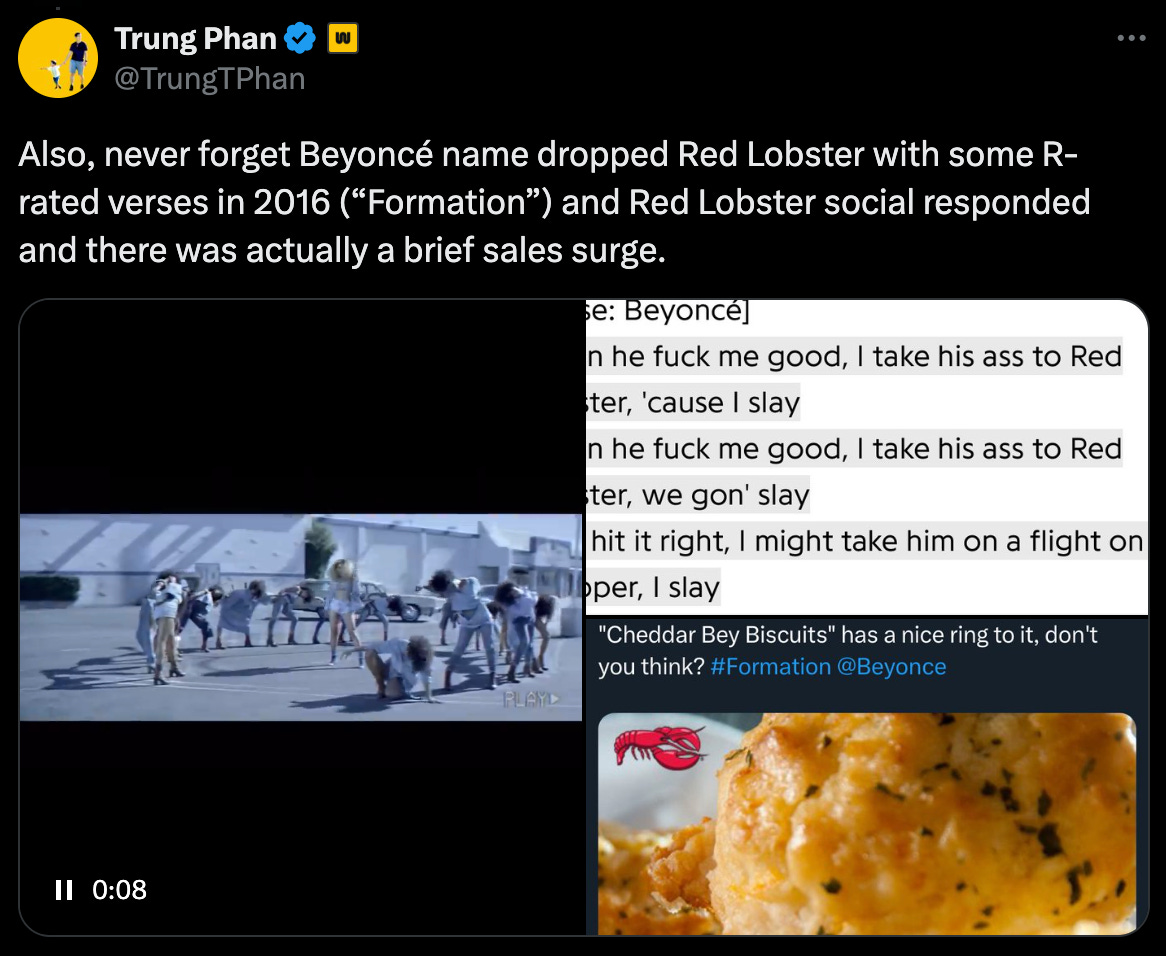

Red Lobster filed for bankruptcy: Man, I used to hit Red Lobster so hard as a kid. It was definitely a treat for the family to smash some scampi, lobster and infinite cheddar biscuits. But the restaurant chain — with 500+ locations in North America — has had a rough few years and declared for bankruptcy this week.

A popular joke was that Red Lobster failed because greedy customers took advantage of its “$20 Endless Shrimp” promotion. This is only a small part of the story. The chain does $2B a year in sales but bleeds money and is sitting on $1B debt with only $30m in cash. Mismanagement — it has had 5 CEOs in the past 5 years — and private equity (PE) tomfoolery wrecked the business, per The American Prospect:

In 2014, Golden Gate Capital (GGC) acquired Red Lobster for $2.1B. It was able to recoup most of the investment by selling off the real estate owned by the restaurant for $1.5B. GGC then rented the stores back at an above market rental rates (this is a standard PE move known as a sales leaseback).

In 2016, GGC sold a 25% minority stake for $575m to Thai Union — a Thai seafood conglomerate that also owns the Chicken Of The Sea brand (that bodybuilders love buying cans of tuna from).

In 2020, Thai Union Group acquired an even larger stake but business was bad. First, COVID sapped demand and raised costs. Second, people just stopped going to Red Lobster with many long-time customers complaining about the deteriorating quality.

In 2023, Red Lobster turned its “$20 Endless Shrimp” from a seasonal promotion to a year-round menu item. The chain lost ~$11m on the deal but the bankruptcy filing alleges that Thai Union was using “Endless Shrimp” — and aggressively promoting it — as a way to dump its own shrimp supply. Thai Union had become the only Red Lobster shrimp vendor, overcharging for shrimp and skipping quality reviews.

The all-time Red Lobster shrimp eating record is apparently 600 pieces in 8 hours. I just puked in my mouth writing the last sentence.

Anyway, Thai Union has written off its $500m+ investment and denies that it was overcharging Red Lobster for shrimp. But if Thai Union's equity investment was worthless, one way to recoup its funds would be to sell its own seafood supply to the restaurant at a mark-up. It sounds plausible. Either way, the PE sales leaseback really hamstrung the business as rents stayed high even as demand — with sales down 30% since 2019 — went away. Red Lobster has already shut 50 stores but raised financing to keep other locations open. Things look grim…and I don’t think Beyonce will be able to fix it again like she did in 2016 (although rapper Flavor Flav might trying be according to his X account).

***

Some other baller links:

I talked about the state of social media with Eric Seufert…it was a blast (Mobile Dev Memo Podcast)

Interesting podcast on “The lost subways of North America”, which explains how cars came to dominate the continent at the expense of subway lines. (99% Invisible)

“If Scarlett Johansson pursues legal action against OpenAI for giving ChatGPT a voice she calls ‘eerily similar to mine,’ she might claim the company breached her right to publicity.” (Wired)

…and them fires posts:

Finally, Google started rolling out its “AI Overview” for certain search results. It’s been a disaster with some demented suggestions including: 1) using gasoline to make spaghetti spicier; 2) drinking urine to hydrate yourself (I mean, technically possible, but maybe not the best advice).

Google’s current business dilemma is wild. Embrace generative AI — which is the the future modality — and put the $300B search ad business at risk. Or do nothing and watch it all get whittled away.

You can see tension in this thread of poor results.

Absolutely fantastic writing. I enjoyed the references also so that we could see where Jerry Seinfeld started and the Esquire article influenced. Well done Trung!

I wish it were this easy. Knowing you're stuck or somewhere on that plateau doesn't make it a bit less painful. I believe those that "made it" on this journey endured the pain and kept going because the pain of not doing it was bigger, way bigger than the pain it took to do it. Show them the charts and they will despise them. If words and charts can describe it, it wouldn't be that hard.