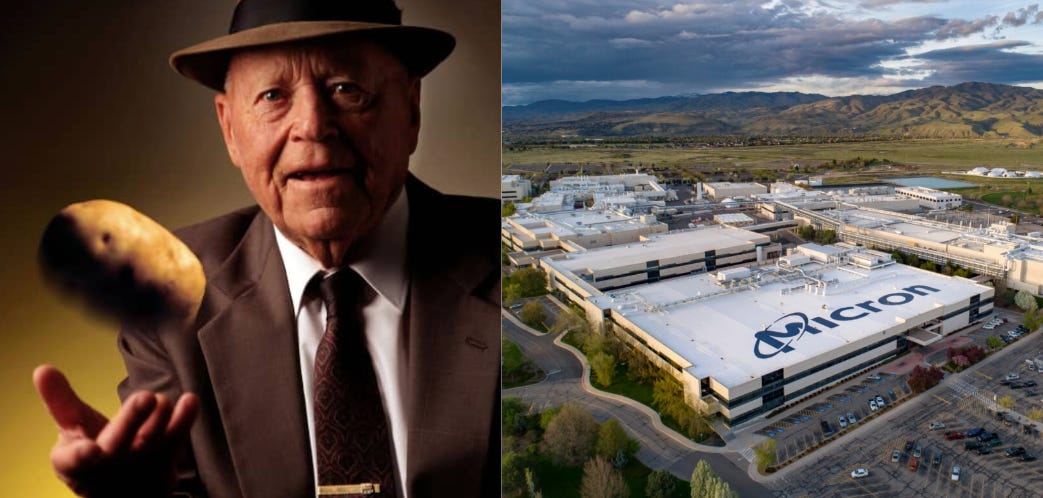

J.R. Simplot Became A Billionaire Selling Potato Chips (and then Semiconductor Chips)

How J.R. Simplot went from the largest seller of french fries to McDonald's in the 1960s to the largest shareholder of Micron Technology in the 1990s.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we will talk about J.R. Simplot, a potato farming billionaire who went on to build what is now the $220B+ semiconductor firm Micron Technology (an all-time business pivot with some lessons for the current AI gold rush).

Also this week:

ChatGPT x Walmart

MrBeast Thumbnails

…and them wild posts (…including Toy Story 5)

I recently finished Chris Miller’s book Chip War, which traces the geopolitical history of the semiconductor industry (and also serves as a 474-page reminder that I misallocated my portfolio during COVID to animal-themed NFTs and 15-leg parlays instead of Nvidia).

My favourite bit from the book was about J.R. Simplot, an Idaho potato farmer who used his understanding of commodity markets to spot an opportunity in the dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) segment of the semiconductor industry.

And by “an Idaho potato farmer”, I mean “the person who became a billionaire supplying McDonald’s with 50% of its french fries and used to drive around the city of Boise with a license plate that read SPUD”.

Just absolute boss moves.

In 1980, he invested $1m into Micron Technology for a 40% stake, which would eventually make him a billionaire again just from memory chips (or as Russ Hanneman would say, “re-billion-izing”).

Simplot’s unlikely career pivot was widely covered in the 1990s with some top-tier headlines:

1992: The Idaho Angel On Their Shoulders (The Washington Post)

1995: The Simplot Saga: How America’s French Fry King Made Billions More in Semiconductors (Fortune)

1996: From Mr. Spud to Mr. Chips (The New York Times)

While Simplot passed away in 2008, Micron Technology remains a major semiconductor player with a market cap of $220B+. The company has also been in the news in recent years as part of the US-China trade war.

We’ll discuss that later but first let’s walk through Simplot’s wild career journey from potato chips to semiconductor chips:

Simplot’s Potato Empire

Micron and the Memory Opportunity

Winning The DRAM Market

Micron, China and the Future of AI

Simplot’s Potato Empire

John Richard Simplot (aka “J.R.” aka “Jack”) was born in 1909. His family moved from Iowa to Idaho — America’s largest potato exporting state — when he a year old and Simplot would live for nearly another century.

His birth year is a great starting point to understand the unlikeliness of his later success in tech manufacturing.

Just look at the semiconductor industry’s most iconic names in the second half of the 20th century. They were all born much later than Simplot:

Jack Kilby invented the integrated circuit and was born in 1923.

Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore founded Intel and were born in 1927 and 1929, respectively (legendary Intel CEO Andy Grove was born in 1936).

Morris Chang was a key figure at Texas Instruments before founding Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and he was born in 1931.

Jerry Sanders co-founded AMD and was born in 1936.

Jensen Huang and his glorious collection of Tom Ford leather jackets wasn’t born until 1963.

Simplot was more age contemporary with key figures from Bell Labs who conducted pioneering research on solid-state physics and transistors, but played less of a part in commercializing the technology: John Bardeen (1908) and William Shockley (1910).

While Simplot didn’t grow up in a computing revolution, he was no stranger to cutting-edge technology. It was cutting-edge agricultural technology, as explained by Fortune:

Mr. Simplot got his start in 1923 at the age of 14. After storming out of his father’s house in a huff, young Jack set himself up as a hog farmer. His break came during a harsh winter, when feed grain was in short supply, but potato scraps and wild horse meat were plentiful. He adapted the latest boiler technology into a rendering vat that produced a fortified hog slop. The next spring, when his competitors led their scrawny survivors to market, Jack Simplot made a killing with his fat hogs.

Simplot initially funded the business with some insane hustle.

His mom gave him $80 when he left the house. He found accommodation at $1 a night, then pulled an incredible arbitrage with local teachers he knew.

How? These teachers were holding interest-bearing paper called “scrip”. Some of the teachers needed cash up front and couldn’t wait until the scrip matured. So, Simplot offered cash for 50% of the face value of the scrip. He then took out a loan at a bank using that scrip as collateral and bought $600 worth of pigs.

AND ALL AT FOURTEEN YEARS OLD!!

I was making my way through a box set of Goosebumps books at the same age.

That was one high-agency pre-teen.

The next time a friend tells you “they’ve been grinding so hard”, ask them “how many pigs have you fed today by boiling potato scraps and wild horse meat?”

When they reply “huh?”, tell them “that’s what I thought” with a knowing nod and expect them to then cut off all future communications.

Anyway, that first score for the young entrepreneur put him down the path of not needing a formal education. Indeed, Simplot never graduated from high school. He just kept commercializing new machines that took potatoes as an input and filled his pockets with filthy fiat as an output:

The next machine that grabbed Simplot’s attention was an automatic potato sorter. Then still in his teens, Simplot and a partner ordered one of these machines.

Simplot owned a 50% share and won the other half in a coin toss. That machine gave him a monopoly on the fast sorting of potatoes in Idaho, and Simplot was on his way to his first million.

Another technological breakthrough: food dehydration. On a trip to California in 1940, Simplot saw an old prune drier adapted to drying onions. He ordered one and used it to create dehydrated potatoes, which fed the troops in World War II. That device helped make him an even wealthier man.

His next breakthrough was successfully freezing potatoes, which had never been done until one of Simplot’s engineers discovered that the trick was blanching and compressing.

The potato-freezing technology caught the eye of one Ray Kroc in the mid-1960s. A decade earlier, Kroc had started franchising McDonald’s locations and was in the market for frozen french fries (or “chips” for all you UK and Australian folk).

Simplot would soon supply McDonald’s with half of its spud requirements and became a billionaire in the process (and this was back when being a “billionaire” was a true rarity in America for anyone not descended from a Carnegie or Rockefeller).

You know what else was invented in the mid-1960s other than french fry freezing technology and hippies dropping acid while doing swinger swaps at outdoor music festivals?

A new type of memory architecture for semiconductor chips: dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), which set the table for Simplot’s re-billionization a few decades later.

Micron and the Memory Opportunity

In 1966, IBM researcher Robert Dennard began research on how integrated circuits could more efficiently store data. His eventual breakthrough with DRAM was crucial for the future miniaturization and personalization of computing.

Chris Miller explains the problem that Dennard was trying to solve:

Before the 1970s, computers generally “remembered” data using not silicon chips but a device called a magnetic core, a matrix of tiny metal rings strung together by a grid of wires. When a ring was magnetized, it stored a 1 for the computer; a non-magnetized ring was a 0. The jungle of wires that strung the rings together could turn each ring’s magnetism off and on and could “read” whether a given ring was a 1 or a 0. The demand for remembering 1s and 0s was exploding, however, and wires and rings could only shrink so far. If the components got any smaller, the assemblers who weaved them together by hand would find them impossible to produce. As demand for computer memory exploded, magnetic cores couldn’t keep up.

Dennard’s solution:

[Dennard] began envisioning integrated circuits that could “remember” more efficiently than little metal rings. Dennard had long, dark hair that flowed below his ears, then shot out at a right angle, parallel to the ground, giving him the look of an eccentric genius. He proposed coupling a tiny transistor with a capacitor, a miniature storage device that is either charged (1) or not (0). Capacitors leak over time, so Dennard envisioned repeatedly charging the capacitor via the transistor.

The chip would be called a dynamic (due to the repeated charging) random access memory, or DRAM. These chips form the core of computer memory up to the present day.

The DRAM patent was issued in 1968.

Intel was founded the same year and launched a DRAM chip in 1970. Along with Texas Instruments, Intel dominated the nascent DRAM market until competition from Japan (Toshiba, NEC etc.) totally changed the industry.

It’s worth taking a quick detour to understand the Japanese economy after World War II. For the first two decades, the country moved up the manufacturing ladder with the assistance of American funds and consumer market. They started with textiles and other low-value add goods but were not known for high-end manufacturing or innovation.

Take Sony. It won plaudits in the 1950s for transistor radios but this was scaling up existing technology. In 1968, it scored a hit with the iconic Trinitron Color TV and the immortal Walkman came out 11 years later in 1979.

When Intel launched its DRAM product, American chipmakers trolled their Japanese counterparts by calling them the “click, click” country (the sound Japanese engineers made with their cameras to copy other people’s ideas).

But Japan levelled up its game for the that juicy DRAM cash. In fact, makers of American DRAM chips in the period showed failure rates — the number of malfunctioning chips — that were 4.5x to 10x higher than the same Japanese chips.

Further, the DRAM market was an ideal target for Japanese industrial policy that fused government and private sector interests. DRAM is a largely commodity (and low margin) product that requires a massive up-front capital investment for the construction of fabrication plants (fabs). These fabs takes years to complete, which leads to boom-bust cycles.

People demand memory chips —> Spend beaucoup bucks to build fabs —> By the time a new memory chip fab is ready, there is lower demand —> The market gets oversupplied and prices nosedive —> Less money to invest in new fabs —> People are forced to cancel streaming subscriptions and scale back DoorDash food delivery —> The demand for memory chips rise again —> Supply isn’t ready, so prices shoot up —> Spend beaucoup bucks to build fabs….

Japanese chipmakers were able to better navigate this cycle in the 1970s, per Miller:

[Japanese DRAM firms] got access to far cheaper capital. Chipmakers like Hitachi and Mitsubishi were part of vast conglomerates with close links to banks that provided large, long-term loans. Even when Japanese companies were unprofitable, their banks kept them afloat by extending credit long after American lenders would have driven them to bankruptcy.

Against this type of competition — which has many parallels with China in the 21st century — Intel couldn’t stay afloat in the DRAM market. By 1985, most American chipmakers stopped making DRAM and Japanese tech was ascendant, with the country responsible for 46% of global CapEx on semiconductors while America was at 35%.

Don’t cry for Intel, though. Andy Grove pivoted the chipmaker to microprocessors including a deal with IBM for home PCs, which led then led to the Wintel partnership with Microsoft and William Henry Gates III (well actually, you can cry for long-term Intel investors who are looking at basically the same market cap that INTC had in 2000).

Ok cool, what does any of this have to do with potatoes?

Well, in 1978, twin brothers Joe and Ward Parkinson decided to launch a DRAM manufacturing firm in Boise, Idaho. It was a long-shot idea considering the Japanese competition and industry economics. As a business venture, this had worse odds than Rob Schneider ever winning an Academy Award for Best Actor.

To compound the challenge, let’s just say the Boise Technology Angel Investing Facebook Group was not very active at the time (the famous angel check from that period was probably Ross Perot giving Steve Jobs $20m for 16% of NEXT Computer in 1986).

But J.R. Simplot was very much around and the DRAM market had a number of similarities to the spud market, as Miller explains:

Micron had to raise funds the hard way. Micron cofounder Ward Parkinson had gotten to know a Boise businessman named Allen Noble when he waded through Noble’s muddy potato field in a business suit trying to find a malfunctioning electric component in an irrigation system. The Parkinson brothers parlayed this connection into $100,000 in seed funding from Noble and a couple of his wealthy Boise friends. When Micron lost its contract to design chips for Mostek and decided to make its own chips, the Parkinsons needed more capital. So they turned to Mr. Spud, the richest man in the state.

The Parkinson brothers first met Simplot at the Royal Café in downtown Boise, pouring sweat as they delivered their pitch to Idaho’s potato plutocrat. Transistors and capacitors didn’t mean much to Simplot, who was as close to the opposite of a Silicon Valley venture capitalist as you could get. He’d later preside over impromptu Micron board meetings each Monday at 5:45 a.m. at Elmer’s, a local greasy spoon that served stacks of buttermilk pancakes for $6.99.

However, as all of Silicon Valley’s tech titans were fleeing DRAM chips amid the Japanese onslaught, Simplot instinctively understood that Ward and Joe Parkinson were entering the memory market at exactly the right time. A potato farmer like him saw clearly that Japanese competition had turned DRAM chips into a commodity market.

He’d been through enough harvests to know that the best time to buy a commodity business was when prices were depressed and everyone else was in liquidation. Simplot decided to back Micron with $1 million. He’d later pour in millions more.

Simplot received 40% of Micron Technology for that $1m. On signing the check, he said, “Boys, it’s a gamble, and we’re going to take it.”

However, it was less of a gamble than it looked because Simplot’s was one of the world’s foremost experts on the following combination of words: “commodity market”, “prices were depressed” and “everyone else was in liquidation”.

He had a playbook.

Winning The DRAM Market

With Simplot’s backing, the Parkinson twins wasted no time and proved their mettle.

They built a chip fab in 1981 for ~$10m, which was 10% the typical construction cost and were selling 64k DRAM chips the next year.

Then, Micron Technology went public in 1984 just as the Japanese firms turned the competition dial to 11.

“They dropped the price of DRAMs from $2 to 25 cents and kept it there for 18 months,” Simplot said about the period. “They were dumping!”

Intel and 10 other American DRAM makers dropped out of the market, leaving Micron Technology and IBM as the domestic producers (and IBM kept the chips for internal use).

How did Micron Technology hang around?

They followed Simplot’s motto of becoming “the lowest-cost producer of the highest-quality product.”

A few key factors:

The Idaho Advantages: Micron had access to cheaper land and energy (particularly hydroelectric power) as compared to Japanese and California competitors. Also, ambitious people in Idaho who wanted to work in tech didn’t have many other options (in Chip War, one Micron employee says, “We didn’t have something else to do. We either made DRAMs, or game over.”). The difficult boom-bust DRAM business also meshed well with the state’s “hardworking, blue collar work ethic.”

Manufacturing and Process Innovation: Per Miller, “…most of [Micron’s] competitors were fixated on shrinking the size of transistors and capacitors on each chip, [but] Ward realized that if he shrunk the size of the chip itself, Micron could put more chips on each of the circular silicon wafers that it processed.

Next, Parkinson and his lieutenants simplified the manufacturing processes. The more steps in manufacturing, the more time each chip took to make and the more room for errors. By the mid-1980s, Micron used far fewer production steps than its competitors, letting the company use less equipment, cutting costs further.

They tweaked the lithography machines they bought from Perkin Elmer and ASML to make them more accurate than the manufacturers themselves thought possible. Furnaces were modified to bake 250 silicon wafers per load rather than the 150 wafers that was industry standard. Every step of the fabrication process that could handle more wafers or reduce production times meant lower prices.”Flaws in Japan’s Business Model: We talked about how the Japanese DRAM firms had access to cheaper capital and other forms of government support. While this arrangement kept the factories humming during market pullbacks, it also meant the manufacturers had less cost discipline. Output was more important than profit.

On the last point, Micron Technology became one of the loudest voices for the US government to take action against unfair Japanese trade practices.

Micron Technology had become the industry’s lowest-cost producer and was ready for a price war but it still wanted government assistance to deal with Japanese firms “dumping” of product.

This trade issue was also personal for Simplot. The Japanese had put tariffs on his spuds (reminder: Japanese potato sticks go so hard) and he was not happy:

“They’ve got a big tariff on potatoes. We’re paying through the nose on potatoes. We can out-tech ’em and we can out produce ’em. We’ll beat the hell out of ’em. But they’re giving those chips away.”

Ultimately, his lobbying helped lead to the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Trade Agreement in 1986. The Reagan administration placed a 100% tariff on $300m worth of Japanese semiconductors and Japanese chipmakers agreed to reduce the quantity of exports. Further, the Japanese government agreed to allow foreign firms to gain up to 20% share of the Japanese market.

This wasn’t the first time that Simplot played hardball in business. We’re talking about someone that survived The Great Depression and lived through World War II. He went a bit too hard in the late 1970s and was even booted off of the New York Mercantile Exchange for manipulating Maine potato futures (what a wild sentence and no wonder the subtitle for his biography reads “A Billion The Hard Way”. ).

The U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Trade Agreement would prove controversial. Why? The lower supply of DRAM chips hurt many American electronic manufacturers downstream because they had to deal with shortages and pay higher prices.

These higher prices brought in new competition from South Korea (keep this in mind).

Meanwhile, Micron Technology lobbied itself into a sales increase of 6x between 1986 and 1988. Those margins were so so thin, though. In its first decade of business, Micron Technology saw revenue grow 100x from $3m in 1981 to $300m+ in 1990 (profit was only $5m, equal to a teeny tiny 1.6% profit margin).

But as a low-cost producer, Micron capitalized on economies of scale to stay in the game along with South Korea’s Samsung and SK Hynix (while nearly every other Japanese and American competitor dropped out).

“In 1993, the U.S. retook first place in semiconductor shipments,” Miller writes in Chip War. “In 1998, South Korean firms had overtaken Japan as the world’s largest producers of DRAM, while Japan’s market share fell from 90% in the late 1980s to 20% by 1998.”

While the DRAM market changed in the mid-1990s, Simplot remained the largest owner of Micron Technology with a ~20% stake and overall net worth of ~$5B (William Henry Gates III was the world’s richest person at $15B).

While Simplot wasn’t working day-to-day at the Micron fabs — and even had a falling out with the founding Parkinson brothers (who both left the company) — he was instrumental in decision making, as detailed in the Fortune piece:

During Micron’s crisis years [in the 1980s], the board began meeting every Monday morning at Elmer’s Pancake House. It’s a habit that stuck like syrup to a napkin.

Even though the company now [in the 1990s] has billions in revenue, the board still gathers at Elmer’s — where two ceramic pigs stand guard on top of a rotating cake display — once a week at 5:45 A.M.

Get there after six and Simplot will cock his head and ask, “What’s the matter, did you sleep in?”

For breakfast Simplot passes on the short stack (which isn’t bad) and orders a bowl of raisin bran. He’s known to steal a few strips of bacon from the plates of other board members.

The “did you sleep in” combined with sniping bacon strips is just S-Tier psychological warfare. But for Micron execs, giving up that bacon was worth it and they made the bacon because Simplot used experience he gained in building a potato empire to win the DRAM battle: from deploying capital to understanding commodity markets to working the political system.

Micron, China and the Future of AI

Today, Micron Technology is worth $220B+ and is one of the largest employers in Boise. It still dominates the DRAM market along with SK Hynix and Samsung (the three have a combined market share of 90%+ in DRAM and also the specialized high-bandwidth memory, aka HBM, architecture used widely in generative AI).

The last major Japanese competitor was Elpida. It was a consolidation of failing Japanese DRAM firms and Micron ended up acquiring the operation in 2013.

Taiwan spent billlies trying to enter the DRAM market but couldn’t manufacture the chips profitably.

In 2015, the Chinese state-backed technology firm Tsinghua Unigroup tried to buy Micron for $23B and…c’mon…that wasn’t going to happen. This overture began a decade of Micron Technology becoming a pawn in the US-China trade conflict.

In 2020, Micron says China stole valuable IP. In 2023, China banned the use of Micron in critical infrastructure. Just last week, Micron completely exited China’s AI data centre market. The Idaho-based chipmaker is still allowed to sell to Chinese automakers and mobile firms but will definitely take a hit on its $3.4B of Chinese-linked revenue (equal to 12% of its $28B in the past business year).

The other part of the Micron story that remains relevant in the age of AI is Simplot’s wild business pivot.

One quote summarizes it perfectly. During the release of Windows 95, someone asked Simplot about using computers. Well, Simplot never owned a PC and he hammered home the point by dropping this bar: “Hell, boy, I came before the goddamn typewriter.”

With or without a PC, Simplot’s knowledge of potato economics proved extremely valuable for Micron.

The current AI boom is so all-encompassing that we’re seeing the value of different industry experiences driving everything forward.

Elon’s career in energy innovation and running massive manufacturing plants was pivotal in xAI building a $6B AI data centre in 122 days (a feat that typically takes 2-3 years).

Sam Altman’s previous career running start-up incubator Y-Combinator made him one of the world’s foremost dealmakers, fundraisers and capital allocators. These tools are coming in handy since OpenAI needs to financially engineer $1T in capex spend and scale a business to $100B in revenue in less than 5 years.

In 50 years, we’ll look back at this period and find stories of people in wildly different industries applying random domain-specific knowledge that unlocked AI in a new way…although it’s unlikely any of them would have started their careers by boiling wild horse meat and potato scraps.

This issue of SatPost is brought to you by Bearly AI

Are you looking for a no-logging, encrypted and anonymized AI chat tool?

Then try the Bearly AI research app, which provides an easy-to-use UX for the newest models from OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, DeepSeek, Gemini and more.

While some AI providers keep chat logs indefinitely even after a user deletes them...Bearly AI has a default no-logging policy and user chats are encrypted while requests to LLM providers are completely anonymized.

Try one month FREE of the Pro Plan using the code BEARLY1.

ChatGPT x Walmart

We briefly touched on Sam Altman’s deal-making in the piece about J.R Simplot and Micron…but it’s worth unpacking the recent run of OpenAI announcements because it’s getting out of control.

ChatGPT is the most important consumer AI product and AI is basically propping up the entire US economy right now: AI data centre buildout accounts for ~2% of US GDP and was responsible for ~40% of GDP growth in the first half of 2025.

With 800m weekly users, ChatGPT is gonna hit the billy club soon along with Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, Telegram, YouTube and — damnit — LinkedIn.

This is 3 years after launch. Insane.

The math doesn’t look to be mathing on the financials, though. For 2025, OpenAI is projected to lose $20B on revenue of $13B while it’s committed to 26GW of AI data centers worth more than $1T.

This is why Altman is throwing Olive Garden Never Ending Pasta Bowl levels of spaghetti at the wall, per the Financial Times:

OpenAI is working on new revenue lines, debt partnerships and further fundraising as part of a five-year plan to make good on the more than $1tn in spending it has pledged to create world-leading artificial intelligence.

OpenAI is planning on deals to serve governments and businesses with more bespoke products, creating more income from new shopping tools, and new sales from its video creation service Sora and AI agents, said multiple people familiar with the start-up’s efforts.

It is also weighing ways to cash in on its intellectual property by developing new AI infrastructure, making forays into online advertising and plans to launch consumer hardware products, including a new AI-powered personal assistant device, with former Apple star designer Jony Ive.

Over the past few months, it’s clear that the market wants to believe that Altman’s high-wire act will pan out and many tech stocks have popped on OpenAI announcements:

Oracle received a $300B data centre commitment from OpenAI (ORCL gained +36% on news)

Shopify and Etsy were added to ChatGPT checkout feature (SHOP +6%, ETSY +16%)

Nvidia intends to invest $100B into OpenAI (NVDA +5%)

SK Hynix and Samsung agree to partnerships with OpenAI for advanced memory chips (SK Hynix +10%, Samsung +4%)

AMD agreed to sell OpenAI 6GW worth of chips for AI data centers and also gave the startup warrants worth 10% of AMD (AMD +23%)

Broadcom announced a partnership to build a custom chip for OpenAI (AVGO +10%)

The most recent major OpenAI partnership came last Tuesday: shoppers will soon be able to buy non-perishable Walmart items directly from ChatGPT.

Did Walmart’s stock pump on the news? Is the Pope Catholic?

Of course it did. The Bentonville, Arkansas retailer took Altman’s pixie dust and gained 5% to a record market cap of $850B.

It’s the latest tech move by the world’s largest seller of individual bananas (true story) to take on Amazon (which it has sharply outperformed in the past 5 years: WMT +131%, AMZN +34%):

Walmart’s e-commerce sales hit $100B in 2024; while still short of Amazon’s $480B, WMT’s online business is growing 20% a year (vs. 10% a year for AMZN).

Online ads were $4.4B in 2024, up 30% YoY (while less than 1% of Walmart’s total sales, high-margins on ads make it 10% of Walmart’s operating profit).

Walmart has turned its supercenters (which usually stock 120k SKUs) into online distribution hubs (100s of millions of SKUs now).

Wall Street is recognizing the change and Walmart’s P/E is ~40, more than that of Amazon, Apple, Meta or Microsoft (WMT has outperformed all of them in the past year).

Walmart’s digital success is bolted onto the largest real-world retail operation, per The Economist:

“With $680B in revenue [for 2024] and 2.1m workers, it is the largest company in the world on both measures.”

“In America it takes in a 1/10th of all retail spending, excluding cars, and a quarter of the outlay on groceries.”

“Walmart has some 5,000 stores across America; 90% of Americans live within 10 miles (16km) of one.”

Uses its size to get major discounts and items are 4-5% cheaper than Target (and 8-10% cheaper than other grocers).

How will Amazon respond?

The $2.3T behemoth founded by Big Daddy Bezos is actually in a tricky position. While ChatGPT is an important (and perhaps dominant future) distribution channel, Amazon has spent decades building an e-commerce walled garden and has a lot more at risk than Walmart.

Still, Ben Thompson believes the trade-off is worth it:

Now the big question is: Will Amazon follow Walmart’s lead? The answer is not obvious (and Amazon isn’t saying). Unlike Walmart, Amazon is the dominant e-commerce site, so doing anything to encourage shoppers to go elsewhere could be counterproductive. Moreover, working with ChatGPT or another chatbot would be an admission that its own AI features aren’t cutting it. (When was the last time you used Amazon’s e-commerce chatbot, Rufus?) Plus, having more shoppers search outside Amazon’s site would likely undercut its gargantuan advertising business, which is largely made up of merchants and brands paying to boost their products in search results on its website.

On the other hand, if you believe a big chunk of online shopping in the future will take place through chatbots, refusing to work with OpenAI in 2025 could be akin to refusing to let Google index your website in 2000. What’s more, if Amazon were to do a big e-commerce deal with OpenAI, it could pave the way for OpenAI to someday become a large Amazon Web Services customer, just as OpenAI has signed up to use Oracle and even Google Cloud. AWS and OpenAI took a tiny step in that direction in August, when AWS finally started offering OpenAI models to customers—more than two and a half years after ChatGPT became a household name.

Amazon has successfully navigated a similar “frenemy” relationship with TikTok—a large AWS customer but also an increasingly significant competitor in e-commerce. Though Amazon competes with TikTok in online shopping, it decided to start placing shoppable ads on TikTok. That followed an internal debate about whether doing so could hurt Amazon by further boosting TikTok’s appeal as a shopping destination, as we reported last year.

If Amazon was purely a retail company, then CEO Andy Jassy’s calculus of whether to work with ChatGPT’s Instant Checkout might be simpler. But he’s leading a huge conglomerate where what’s good for one business can hurt others. That makes it tough to handicap his final choice.

Either way, I can’t wait until OpenAI goes public and we get this announcement on CNBC.

MrBeast Thumbnails

Bloomberg’s Lucas Shaw has a great profile on Jimmy “MrBeast” Donaldson, the absolute gorilla on YouTube with over 400m subscribers.

MrBeast has taken his massive audience and started selling them products he directly owns under the banner of MrBeast Industries.

In 2024, it made $450m and that was evenly split between videos (300 employees) and his Feastables chocolate bar brand (150 employees). MrBeast Industries also does a Lunchables competitor (Lunchly) but it’s not at the same scale.

The operation was valued at $5.2B after a recent funding round but is still running at a loss:

Right now, however, Beast Industries is hemorrhaging money. It’s had three years of losses, including more than $110 million in 2024. The viral videos account for all of it, overwhelming the profits from Feastables. Donaldson has been spending between $3 million and $4 million on every video he produces for the main YouTube channel, most of which lose money. In 2023, Beast spent $10 million to $15 million shooting videos it never released to the public because they weren’t up to its standards. He also lost tens of millions of dollars producing Beast Games, a popular show for Amazon Prime Video in which 1,000 people competed for $10 million by, among other things, moving a 10,000-pound boulder.

MrBeast recently hired 55-year old Jeff Housenbold, a veteran of Silicon Valley (eBay, Shutterfly) to professionalize MrBeast Industries. In recent weeks, they’ve announced plans to get into banking and mobile phone plans. These make a lot of sense. The lifetime value (LTV) for these industries are high. The offerings between competitors aren’t too different. So, the ability to acquire customers cheaply is a major advantage.

And here’s my favourite example of Housenbold finding some low-hanging fruit:

Donaldson has learned, though, that he doesn’t always need to spend more money to drive viewership. There isn’t a huge difference between giving away $1 million and $100,000; an average viewer sees both numbers as big and will tune in for the results. In fact, giving away $1 million sometimes suppresses viewership. “We definitely found the point where more money doesn’t equal more views,” Donaldson says. “If I were to give a random person on the street a million dollars, a lot of people who see that video, especially because we have a very international audience—they just don’t think it’s real.”

Final fun fact: MrBeast employs more than a dozen people to make YouTube thumbnails…and they really are the best to do it. INSTANT CLICKS RIGHT HERE.

Links and Memes

Some other links for your weekend consumption:

RIP Diane Keaton: The legendary actress died at 79. Her 50+ year career included a range of roles from drama (The Godfather trilogy) and comedy (Annie Hall, Father of the Bride, Something’s Gotta Give). She won Best Actress opposite Woody Allen in 1977’s Annie Hall and probably has the most iconic ending shot in film history.

United Airlines is offering Starlink Wi-Fi…on its mainline fleet. Last year, WSJ’s Joanna Stern explained why Starlink’s Wi-Fi is so much better than existing airplane Wi-Fi. TBH, crappy airplane Wi-Fi was one of the best ways for me to smartphone detox and actually finish books. I’ll need to find a new reading hack.

The World’s first Waymo DDoS attack…”50 people went to San Francisco’s longest dead-end street and all ordered a Waymo at the same time”. Great piece of performance art but also idiotic for protesting automation when you realize how many lives will be saved by autonomous vehicles.

OpenAI top 30 token users…aka people who have used over 1 trillion tokens including Duolingo, Salesforce, Indeed and Shopify.

Drake sued UMG for promoting Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us”…but the judge dismissed the lawsuit because when Kendrick called Drake a ped0, he did so in the context of a rap beef. No, for real, the judge literally went line-by-line through all the songs and opined on the relevant lyrics. It’s an incredible read.

Speaking of edgy songs…absolutely nothing in the world will prepare you for the lyrics (or music video) for a raunchy country song called “Country Girls Make Do” that has gone extremely viral on TikTok because people make reaction videos of their family listening to it for the first time.

“Using a Urinal Wearing Khakis”…is one of the funniest clips I’ve seen in 2025 via comedian Andrew Rousso.

Spotify will post video podcasts from The Ringer on Netflix…both of these companies are competing with YouTube (which just dominated in total view time). A comparison I’ve seen thrown around is YouTube is Amazon while everyone else in e-commerce (eg. Shopify, Walmart, Etsy, Instacart, Google Shop) try to work together to win share. The reality is that YouTube’s monetization and distribution is so good that posting exclusive to Spotify/Netflix isn’t worth it (even Joe Rogan went back to YouTube).

Since the Gold ETF (GLD) launched in 2004…it has outperformed the S&P 500 (SPY) ETF. Holy smokes. This is what happens when the money printer goes brrrrr, boosting asset values instead of stocks advancing on merits of innovation.

The battle over rare earths…Peter Harrell gives a great overview of how China is weaponizing its monopoly over rare earth refining (and what the rest of the world can do about it).

Apple won US F1 TV rights with a $750m bid over 5 years…the annual rights spend of $150m is significantly more than $90m a year that ESPN was paying. This news comes a few months after Brad Pitt’s film F1 made an Apple-record $630m at the box office. Vincenzo Landino has a great breakdown of the F1 deal numbers.

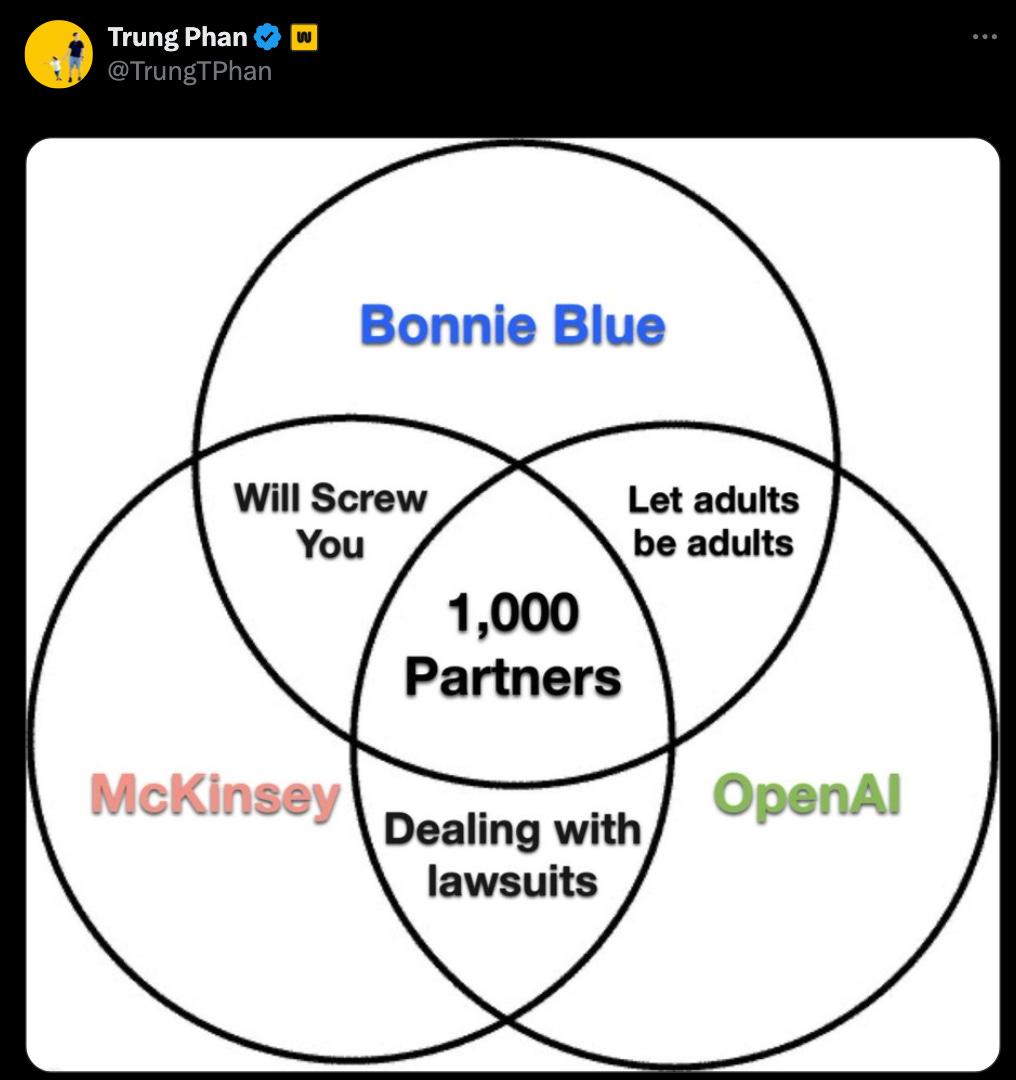

…and them wild posts (including how OpenAI says it will allow adults to generate erotica content in the same week that Google announced it had used AI to discover a “new potential cancer therapy pathway”):

Incredible content/story. Love it!

Love this!