Learning to Slow Down Time

It feels like time is moving faster when we age. How to slow it down? Nature, vacations, events, novelty and random day trips to Disneyland.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we will talk why time seems to pass by faster as we age (and what we can do about it).

Also this week:

Apple’s AI Reveal

Is NYT’s Book List Biased?

…and them wild memes (…including YouTube ads)

I went to Disneyland with my wife and son last month.

It was a random Wednesday in May.

There was no special occasion other than something I saw on Facebook. Well, technically, it was my wife. The only Meta product I still use is my wife texting me “hey, I saw a deal on this Facebook Parenting Marketplace Group”. To which I usually respond, “put the squeeze on” which is code for “can you negotiate it to $0”.

For this deal, we scored a Disneyland family day pass at ~50% off. It actually wasn’t much of a squeeze because the mom selling the pass had already listed it at a steep discount but she was nice and I think everyone got a dopamine hit from the transaction.

The more important detail is why even fly to Anaheim for a short theme park excursion just to have my face ripped off by $10 bottles of water and $30 misting fans?

Here’s the answer: Our perception of time moves faster as we age — which is a very sobering realization — but it’s possible to change this perception and one of the surest ways is to create novel and memorable experiences.

To understand why this is the case, let’s go through the following topics:

Why time feels fast or slow

How to change our perception of time

The experience of my recent Disneyland trip

***

Why time feels fast or slow

I fell down the “how do we experience time” rabbit hole after listening to a podcast by Stanford neuroscientist David Eagleman. His background includes research on “time perception” and he posted a 30-minute episode on the topic titled “Does time really slow down when you're in fear for your life?”

This question was drawn from a near-death experience Eagleman had as a child. When he was 8 years old, Eagleman and his brother were playing at a construction site for a home. They shouldn’t have been there and Eagleman fell off the roof and injured himself badly.

Based on the height of the roof, Eagleman calculated that his fall only lasted 0.6 seconds but his memory of the accident was much longer. In hindsight, it felt like multiple seconds. Explaining why the perception of time was different than the reality of time became a lifelong mission for Eagleman.

While getting his PhD at Stanford, Eagleman interviewed people who similarly experienced time slowing down during a tense situation: 1) a police officer in a shootout; 2) a person in a motorcycle accident; 3) a mother seeing her child fall in a lake; 4) a victim of a mugging.

“These reports made it seem possible to me that the brain has a capacity to operate at a higher frame rate, which is how filming slow motion in the movies works,” Eagleman explains on his podcast. “You capture information at a higher frame rate and then you play it back at normal speed. But what if there was another possibility here? What if, for example, it's a trick of memory such that you're laying down denser memories and when you read it back out, your brain's only conclusion is, ‘well, if I have that much memory, that must correspond to five seconds when in fact it only lasted one second’.”

When experiencing time, our memory plays a crucial role. This is because humans experience time in two ways:

Prospective Timing is forward-looking and involves planning, estimating, or predicting future events or outcomes (example: after some deliberation, I decided to smash half-a-dozen oysters that looked a little bit funny).

Retrospective Timing is backward-looking and involves analyzing or evaluating past events or outcomes (example: after puking my guts out, I reminisce about smashing the oysters and it felt like a few minutes as I internalized all the alarm bells my stomach and nose were sending me).

A more universal example is COVID. Think back to your shelter-at-home routines in 2020 and 2021. In the actual moment, the monotonous daily routine felt like a total drag.

However, those years were a total blur when looking back. Why? Because retrospectively, we weren’t laying down “dense” memories. Every WFH day blended into the next WFH day. Every WFH week blended into the next WFH week. There were few new or novel memories created.

New or novel memories — aka “denser memories” — stretch the feeling of time because they recruit more areas of our brain.

Eagleman attempted to explain this phenomenon with an experiment that placed people in near-death situations. There wasn’t a lot of literature on the topic because … it’s hard to ethically put people in near-death experiences for an academic study. Fair enough!

However, the professor was able to find a clever solution: Eagleman placed research subjects in a SCAD (suspended catch air device) diving machine, an extreme sport contraption that creates a life or death type of reaction.

I suspect that 97% of you are thinking, “WTF is a SCAD?” That was me a few weeks ago before I watched some YouTube videos.

Imagine a 100-foot tower. At the top is a harness device where a person sits — similar to a hammock — while hanging in mid-air before falling straight down. Eagleman tried the SCAD multiple times before signing off on the experiment. He says the SCAD set-up goes against “every Darwinian instinct of survival”. You’re falling backwards with nothing to grab onto and — while a net is waiting below — you don’t see how far you’re falling.

Eagleman had his research subjects do the SCAD while wearing a wristband with a flashing LED screen. Why? Because there is a visual phenomenon called flicker fusion frequency, which is the frequency at which a flickering light appears steady.

If a person’s perception of time really slowed down in near-death situations, the research subjects would be able to identify a number that was flickering at a very high rate while falling (a rate that typically can not be seen by the human eye).

None of the SCAD research subjects could actually identify the number while falling. This suggests that the experience of time in the moment (prospective) did not actually slow down. However, when looking back on the experience (retrospective), all of the subjects overestimated the duration of the fall.

According to Eagleman, the reason why the fall felt longer in retrospect is because the subjects’ amygdala was engaged. The amygdala is the part of the brain that activates the fight-or-flight response in dangerous situations (such as a car cutting in front of you or your wife asking “hey, I’ve been meaning to ask why…”).

“[In] emergency situations, your amygdala commandeers the rest of the brain and makes you attend to what’s happening [vision, audio, feelings, memory],” says Eagleman. “When the amygdala is involved, memories are laid down on a secondary memory system.”

The primary memory system — which sorts through routine everyday activities — is handled by our hippocampus. But most everyday activities are very unmemorable. It’s this secondary memory system that creates long-lasting memories. The memories that are salient many years after the incident. It makes sense. Our survival depends on knowing how to navigate dangerous situations and we want to implant those memories and lessons directly into the dome when they do happen.

There are two main takeaways. First, there is literally no amount of money that you could pay me to do a SCAD. $1 million? Nope. $100 million? Still nope. $1 billion? I will be very upset about this decision — and probably regret missing out on all the Disneyland Misting Fans I could have purchased — but the answer is still nope. Kick rocks.

The larger takeaway is applicable to anyone: engaging more of your brain is crucial for laying down denser memories and stretching out the feeling of the experience of time in retrospect.

***

How to change our perception of time

Eagleman’s ideas have had a particularly profound impact on me based on simple math.

I’m going to commit a statistics crime here but let me lay out a stylized example of how people form memories over the course of their lives: Say the average lifespan is 80 years old. Then consider that time feels like it moves faster as we age. At age 40, the average person may be 50% through their biological life but they may have experienced 75% of what the brain will ever experience.

God damn, that’s too real.

Here’s a longer excerpt from Eagleman’s podcast that really hammers home the realness:

We all have the impression that a childhood summer seemed to last forever, but when you're older, the summers are here and then they're gone and years zip by and decades, zip by. Well, now you know why. It's because the job of the brain is to build an internal model of the world out there. Your brain is locked in silence and darkness inside your skull, and all it is trying to do is understand the structures of the world so it can operate in it better. And whenever it encounters a surprise, it writes that down and it makes changes to your circuitry.

But as you go through life and your brain develops better models of the world, less and less carries much surprise. This is why you lay down fewer memories as you age. It's because you've seen that situation before and you've met that personality before and you've done that job before. The memories that you lay down are much thinner, they're more impoverished. But in contrast, when you're in your childhood, everything is new. And so the richness of your memories gives you the impression of increased duration.

When you are looking back at the end of a childhood summer, it seems to have lasted for such a long time because everything was new. But when you're looking back at the end of an adult summer, it seems to have disappeared rapidly because you haven't written much down in your memory. So I don't recommend emergency situations, but it sure does make you operate like you're a child again. So here is the take-home lesson. We have to seek novelty because this is what lays down new memories in the brain.

Eagleman concludes his podcast episode by explaining practical things he does to lay down denser memories (thankfully, none involve a SCAD):

One thing I do every day is drive home a different route from work. It's not that hard and it doesn't take much longer, but it allows me to see things in a fresh way. Most of us have had the experience that when you drive to work for the first time, it seems to take a really long time, but after that, it shrinks. And it's because you're becoming an automatized zombie and you're just running this program unconsciously of driving to work. You're not noticing new things anymore. And another thing I try to do is rearrange my office every month or so. It's really easy. You just push your desk over to the other side. You maybe swap the artwork on the walls, things like that. These are easy things to do. One thing that I recommend is tonight brush your teeth with your other hand.

It's not that hard to do, but it will make you seem as though you are extending your time a bit because you're forcing your brain off its hamster wheel of doing things a particular way every day. And by the way, if you wear a watch or a Fitbit, switch it to the other hand so that when you are looking at it, it's not just an automatic thing, but it's something you have to put a little bit of attention towards. So all these kinds of things — any version of this — it's the best thing that you can do to perceptually extend your life.

One tip: don’t try to change your daily commuting routine by driving to work in reverse. My personal experience this morning suggests you will get pulled over by the cops.

Anyway, other techniques to extend the experience of time include having “signposts” on your calendar, which are activities that you look forward to doing. Remember, having the same monotonous daily routine bleed into the next same daily monotonous routine is how the experience of time feels short in retrospect. Having different activities to break up a “more of the same” schedule — especially for parents of young children (where routine is routine) — is important.

Geographies with multiple seasons (winter, summer, spring, fall) also extend the perception of time in retrospect. A locale that has a single season for the entire year is more likely to make months blend together. The changing of the seasons acts as temporal signposts.

I know that a lot of SatPost readers spend their professional lives in front a screen.

A day full of Zoom meetings, replying to e-mails and pretending to laugh at your co-workers Slack jokes is a sure way to lay down thin memories. Everyday bleeding into the next.

The biggest life change I’ve done in recent years to counter the digital life is spend at least 90 minutes every day outdoors. It is usually a long walk or jog. While my amygdala is mostly chill, way more parts of the brain are engaged just to keep my body upright and visually locating my next footsteps. It is important to engage all of the senses as much as possible to form dense memories.

This is not just a subjective perception issue, either.

There is also a physics-based rationale.

Let me explain. Duke Professor Adrian Bejan published a paper titled “Why the Days Seem Shorter as We Get Older” and his thesis is that time moves faster as we age because our sensory organs degrade as we age and receive less (or worse) stimuli.

The paper’s abstract reads:

…measurable ‘clock time’ is not the same as the time perceived by the human mind. The ‘mind time’ is a sequence of images, i.e. reflections of nature that are fed by stimuli from sensory organs. The rate at which changes in mental images are perceived decreases with age, because of several physical features that change with age: saccades frequency, body size, pathways degradation, etc.

It is fairly easy to square Bejan’s paper with Eagleman’s take on memory. If our eyesight, hearing, touch and general cognitive abilities degrade as we age, the memories we form will be less dense … and our perception of time will move faster.

Bejan applies this theory of degraded stimuli to the modern media environment:

“Today, many young people experience time distortion because they spend too much time on social media. This has serious consequences, ranging from sleep deprivation to mood changes and mental disorder. This is why an understanding of the physics basis of how humans perceive the passing of time is essential.”

In other words: we all need to touch — see, smell and feel — more grass, no matter the age. Young people do have “more shots on goal” as the saying goes but getting off the phone or computer screen is important.

Which leads us to Disneyland.

***

The experience of my recent Disneyland trip

I know Disneyland currently has a lot of on-the-ground issues, even apart from all the political stuff in recent years. The parks are crowded, expensive and increasingly gamified with the launch of the Genie+ App.1

But the place is great for laying down dense memories.

To be sure, there are many other novel and new IRL activities that can accomplish this goal: concerts, CrossFit, Six Flags, Tough Mudder, puzzle rooms, bowling, an NBA playoff game, picnics in the park, getting sauced at an Octoberfest Beer Garden or TayTay’s Eras Tour.

The key is not to overdo any of the activities — like say go to Disneyland 100x in a year (which is what some annual pass holders do) — because the memories get less dense as the experience becomes more routine.

With all that said, I’m here to give credit to Disneyland and its team of Imagineers a (a glorious portmanteau of “Imagination” and “Engineer”) for crafting a theme park that maximizes the prospective and retrospective memories.

I did a deep dive on the topic last summer after taking my son to Disneyland for the first time (“The Psychology of Disneyland”). There are many aspects of the park’s design that engage all the senses to help lay dense memories:

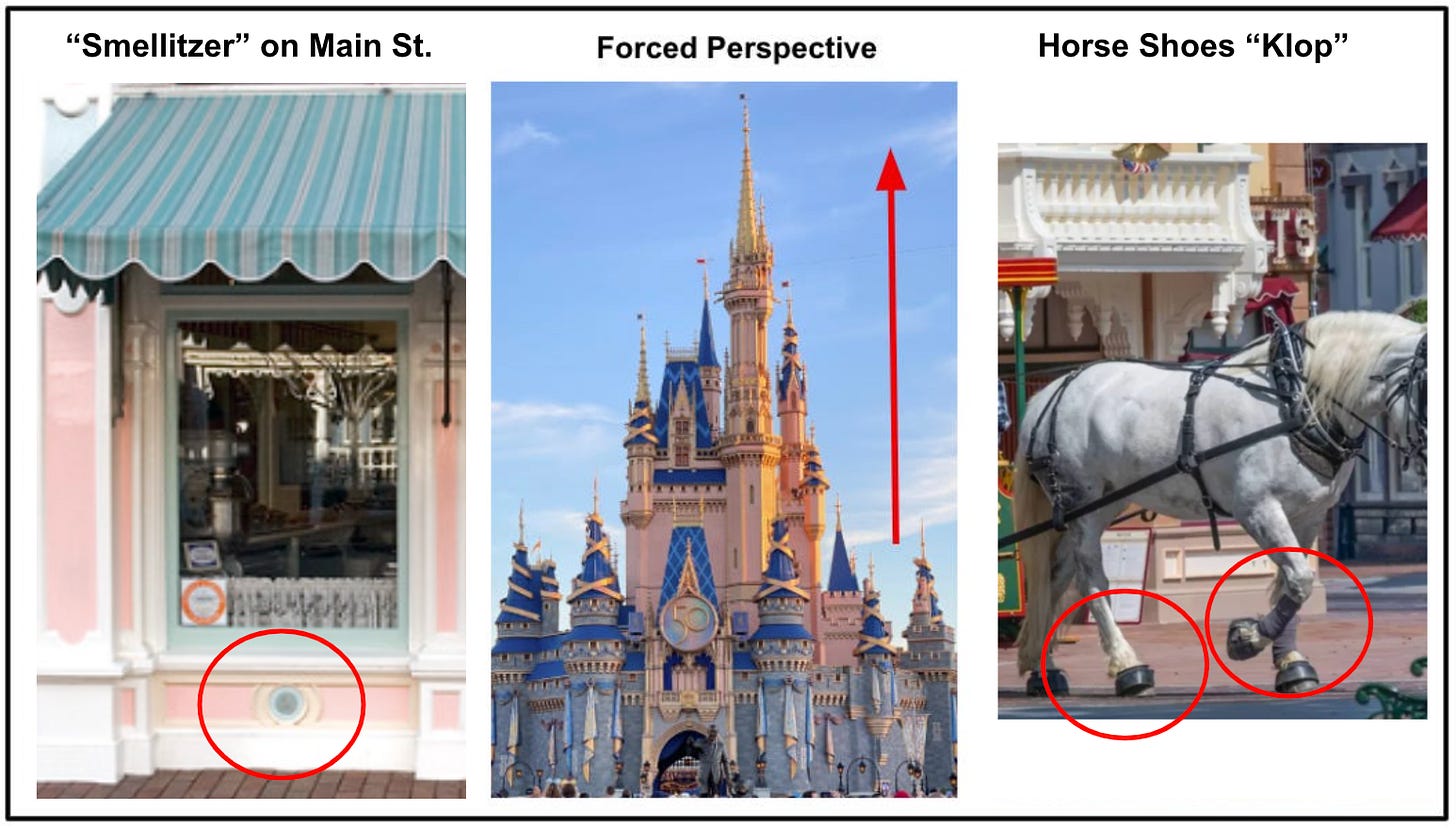

Smell: To utilize the power of smell — which is the sense most-connected to memory formation — a Disney Imagineer literally invented a machine called the Smellitzer to emit lab-created scents which pair with the surrounding attractions. Main Street smells like vanilla. The Pirates of the Caribbean ride smells like salty sea air. Pooh’s Adventure smells like

poohoney. Haunted Mansion smells like burnt wood. The drink carts smell like me overpaying for a $10 bottle of water.Touch: There are various ways to transition between scenes in a film (jump cut, blank screen etc.). At a Disney park, you can literally feel the ground change (eg. gravel to smooth cement) as you walk between different worlds.

Visual Communication: A film technique that Walt Disney really leaned on to build the park was set building. To quickly communicate a story or achieve a desired action, every building structure in Disneyland is built to a specific proportion (eg. 5/8ths of the real size):

Forced Perspective: Imagineers use this technique to make buildings appear larger and taller than they actually are. From a distance, Cinderella's Castle looks larger than life because the bricks at the top are smaller than those at the bottom.

The grass really is greener: Disney World's sidewalks have a reddish hue, which helps make the color of the grass "pop". This is because red and green are complementary colors (i.e. opposite ends of the color wheel), and the contrast makes both the sidewalk and grass appear brighter.

Accentuated Sounds: The horses wear special horseshoes with a polyurethane coating, which makes a louder "clopping" sound when they walk down Main Street.

Before and After Marketing: While a Disneyland trip might only be a weekend, the experience lasts way longer. Disney hypes of anticipation of the trip by sending guests reminders on the lead-up to their arrival. And there are professional photographers all over the park to snap photos for long-lasting memories (PhotoPass lets you view the photos for free online … and just screen shot them if you don’t want to pay for high-res)

I was blown away by the Star Wars world on my trip last year. One goal of our trip this year was to catch the off-season crowds and do the rides without huge lines. The park delivered.

However, the most memorable experience was at California Adventureland, the theme park neighbouring Disneyland that was built in the early 2000s (Walt Disney launched the OG Disneyland in 1955).

The origin story for California Adventureland is interesting from a business perspective. In the late 1990s, Disneyland was facing an attendance problem. It was attracting too many single day visitors. Out-of-town tourists came to Disneyland as one stop on a larger California tour. So, Disney created Adventureland with a variety of famous California sites, such as San Francisco Harbour, 1920s Los Angeles, old Hollywood, and Grizzly Peak.

California Adventureland is a way for visitors to California to lay down dense-ish memories of the state’s main landmarks without having to leave the park.

However, the original launch was a dud as the rides were lacking. In 2012 — 5 years after acquiring Pixar — Disney added Cars Land (based on the Cars franchise) to California Adventureland. Inside Cars Land, Disney built the world’s most expensive theme park ride: Radiator Spring Racers, a roller-coaster type experience built on an electric racing grid that cost $200m.

The park upgrade has been a major success, and California Adventureland has added more rides featuring other Pixar and Marvel characters in recent years. One year before the launch of Cars Land, California Adventureland had 6 million visitors. This increased 33% YoY to 8 million in 2012, and in 2019 — prior to COVID — it reached 10 million visitors.

Radiator Springs Racers is benign by extreme-ride standards (here is a first-person POV on YouTube). However, it still reaches a top speed 64km / hour on sidewinding roads. As you can see in the photo below, my eyes were closed during the ride’s climax and I look like a massive mark but at least the amygdala was engaged (my son bossed it and was completely unfazed).

Looking back, it was a short and amazing trip.

Disney has mastered nostalgia. New parents remember their trips to the park as a child, when they asked their parents to go to Disneyland after consuming content from the rest of the Disney empire (film, TV, songs etc.). Those memories catalyze the new parents to let their kids watch Disney stuff and then those children ask to go to Disneyland.

The nostalgia flywheel is no joke.

But who is Disneyland really for? If novelty is key for forming dense memories as we age, then going to Disneyland actually seems more impactful for adults.

While my son enjoyed this trip to Disneyland, I need trips like it to slow down (the perception of) time.

***

If you want more on Disney’s recent theme park shortcomings, take a look at this 4-hour breakdown of Disney’s Star Wars Hotel from YouTuber Jenny Nicholson. The video is long but so insightful that it went viral and now has ~8 million views. Nicholson comes at it from a fandom perspective but nails the main reasons that Disney’s over-corporatization is hurting the IP. One point that Nicholson calls out is how Disney has given these long names to its attractions — it could be for SEO or branding purposes.

Case in point: the Cars ride I went on is called “Radiator Springs Racers”. Literally, no one calls it that. It’s the “Cars Ride” but for promotional purposes, Disney insists on calling it “Radiator Spring Racers”. Similarly, the Millennium Falcon ride is called “Smuggler’s Run” instead of just “Millennium Falcon”. Guaranteed some McKinsey dunce hat billed $250k for 2-days of work and told Disney to go with the longer name because it does well on Google Search.

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email.

If you press this blue button below, you can save hours of work with AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (the new GPT-4o, Claude Opus 200K) and speech-to-text transcription tools (Scribe, Whisper).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app). Use code BEARLY1 for a FREE month of the Pro Plan.

Links and Memes

Apple’s AI Reveal: At its highly-anticipated WWDC event on Monday, Apple announced its AI product suite. It is called Apple Intelligence (which Apple calls “AI for the rest of us”). Rebranding “AI” as Apple Intelligence is cringe but will probably end up working. These features include voice transcription as well as generative text and images.

To protect its brand, Apple is being conservative with what the tools can actually do. The generative text are re-writes and summaries with other text creation outsourced to OpenAI. The image feature only does animations because Apple doesn’t want people making deepfakes.

Here is a link round-up:

Joanna Stern has a good 5-minute wrap video of Apple Intelligence. The company is running its own small local model on the iPhone with privacy in mind. Anything that can’t be done on the phone is sent to a “Private Cloud” that Apple custom built. These features were demo’d seamlessly for an upgraded Siri, which was launched over a decade ago and has been a consistent source of underwhelming performance. Apple Intelligence will only work for iPhone 15s and beyond (and the features will roll out over the next year). Any queries that are unrelated to information drawn off the phone — personal stuff like contacts, calendars, notes, email etc. — is outsourced to ChatGPT.

Cybersecurity expert Matthew Green has a very interesting breakdown of how Apple’s “Private Cloud Compute” works.

Ben Thompson believes Apple is “right on time” even though people have been roasting the company for taking so long — 20 months since the launch of ChatGPT — to announce AI features. But this is classic Apple. The iPhone maker doesn’t want to be first, it wants to be best. It allows its competitors to flub around before finding the best way to integrate AI across its 1B+ installed devices. The privacy/security angle is a huge play for Apple and Apple Intelligence will be the first real exposure to generative AI for many people.

AAPL stock was down on the day of WWDC but then the market digested the news and Apple has ripped more than 10% since. It added $300B+ to its market cap and overtook Microsoft to become the world’s largest company again. Just massive bags.

Some takeaways:

Will Apple Intelligence drive an iPhone super sales cycle? In recent years, the only real reason to upgrade an iPhone was for a better camera. Now, if people want the Apple Intelligence features — which require top-of-line chips — they will have to pony up for an iPhone 15 Pro or better (iPads and Macs need an M chip to run the AI tools). The iPhone upgrade cycle used to be 1-2 years but the phone has gotten so good, that is is now 3-4 years. I’m still happily using an iPhone 11 and had zero interest in upgrading until now.

Apple is betting on a non-AGI future: The question to consider for Apple and AI: “is the hardware a commodity or is the AI model the commodity?”. Apple is obviously incentivized to make AI the commodity and keep its iPhone as the hub of our digital lives. Apple isn’t paying OpenAI for ChatGPT. OpenAI gets Apple’s distribution. Meanwhile, Apple plans to have integrations with other LLM providers such as Anthropic and Google (which makes the AI models look like the commodity). If actual AGI arrives — as in intelligence that is superior to humans across most intellectual dimensions (like knowing never to go on a SCAD bungee device) — there will be a better way for humans to interact with AI than with a smartphone (think Neurallink or the earpiece from Her). Otherwise, Apple’s insane distribution and ability to integrate software with premium hardware devices are well-placed to keep winning.

Finally, enjoy these Apple posts:

Finally, this video from Dan is A+:

***

Is the New York Times Bestseller List politically biased? The general consensus is that NYT has a liberal bias. If I were to tell you that the NYT's Bestseller Book List disadvantages conservative authors, that probably wouldn’t be too surprising.

Well, The Economist actually ran a study on NYT’s weekly best-selling books and found data to support the intuition: “…on average, books by conservative publishers are 7% less likely to make it onto New York Times weekly bestseller lists than books by other publishers with similar sales figures.”

Here are three potential explanations, per The Economist:

Ideology: This is the obvious rationale. NYT staffers don’t want to promote “views that are unacceptable to the Gray Lady’s staff”.

Bulk Buying: The NYT list down ranks “bulk buying”, which are “purchases that the paper determines are made by institutions or groups rather than individual readers”. This seems to be a known technique to boost the sales of conservative books (however, The Economist did find that — all things equal — conservative books were punished more for bulk buying than other books).

Online vs. In-Store Sales: “Rather than weighting all sales equally, some publishing veterans believe that the paper may place greater weights on sales at independent brick-and-mortar bookstores than online retailers. Independent bookstores, which select titles to order and display, may not stock or give prominence to books by conservatives; online everything is available, and right-wing books fly off virtual shelves.”

This bias mostly dings smaller conservative authors. Stars such as Bill O’Reilly and Glen Beck are still able to top NYT’s list because their numbers are so overwhelming that they can’t be denied. NYT didn’t dispute or confirm analysis but (shocker) told The Economist it doesn’t take an author’s political view into consideration.

As the “paper of record”, NYT should just be calling balls and strikes when it comes to these types of lists. Just show us who the top-selling names are so we can understand the country’s vibes. Sales figures are game-able but still a standardized metric. NYT has just gone full rogue editorial, which is why I now base all my book-buying decisions on whatever has the funniest 1-star review on Amazon.

***

Will Smith is back! Two years after “The Slap” incident at the Oscars, the 55-year old superstar actor had Boy Boys 4: Ride or Die open over the weekend with a strong box office haul of $100m+.

The Town podcast used this performance as a jumping off point for the “Butts-in-Seats Star Ranking”, which ranks which actors and actresses are the biggest global draws right now:

90s Movie Stars: Will Smith blew up in the late-1990s and early-2000s, which was the last true golden age for minting Hollywood stars. It was pre-internet and pre-streaming fragmentation, when actors could reach global audiences regularly for must-see films in theatre. Studios will tap Smith and — to a larger degree — Tom Cruise if they can deliver, despite their off-screen controversies. Less controversial stars from this era that still have serious pull include Leonardo DiCaprio, Denzel Washington and Matt Damon.

The Biggest Fish in the Pond probably isn’t an actor right now. It’s director Christopher Nolan, especially after he took a 3-hour biopic about Robert Oppenheimer to commercial ($976m) and critical (7 Oscar wins). Quentin Tarantino — who says he will only do one more film — is also in the bucket for must-see directors.

Action films travel well globally…because you don’t need to fully understand the plot and high-octane special FX are universal. Guys like Jason Statham and The Rock benefit from this dynamic.

The big question moving forward is if Hollywood can mint any new global stars. Who are the top right now of the next generation? Zendaya? Timothée Chalamet? Tom Holland? Coming off of Barbie, Margot Robbie has a ton of industry capital and could make a run in the decade to come. However, it’s basically impossible for any of them to reach the worldwide stardom of a Cruise, DiCaprio, Smith or ‘Zel from the 90s.

***

Some other baller links:

“How to Build an AI Data Center” (Construction Physics)

“Why Are Arena Tours Selling So Poorly?” (Stereogum)

A Wild Video of How Hot Dog Eating Legend Joey Chestnut Trains (X/Twitter)

…and here them fire posts:

This article definitely slowed down time. By the time I got to the end, I had to scroll back up to see if I was still on the article about slowing down time.

Or, it could just be my aging amygdala.

Great post Trung!