Amazon's $43B ad business, explained

Jeff Bezos long shunned ads. However, Amazon's juicy first-party data has enabled it to compete with Alphabet and Meta in the new digital advertising landscape.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about Amazon’s massive $43B ad business. This is an update to a post I wrote 18 months ago, when this e-mail list was much smaller.

Other stuff this week:

The history of Ketchup (hint: fish sauce)

What happened to 2-sport stars?

And them fire tweets (including Justin Bieber)

One of the wildest running themes for Big Tech is the size of their side hustles:

Apple’s Wearables business (AirPods, Watch etc.) sold $41B in 2022, which is in the ballpark of sales for companies like Volvo ($49B) and Nike ($51B).

Alphabet’s YouTube generates revenue ($29B in 2022) comparable to Netflix ($32B).

It is obviously hard to treat these businesses as standalone (to wit: you can’t pair Apple Watch with an Android phone) and there are broader regulatory concerns. With those caveats, though, you know what might be the biggest Big Tech side hustle?

Amazon advertising.

In Q1 2022, the e-commerce firm officially separated its ad business in company filings (for years, ads had been classified under “other revenue”). The punchline: Amazon’s ad platform is currently on an annual revenue run rate of ~$43B, which is more than the combined revenue of Bing, Snap, Twitter/X, Pinterest and TikTok.

The success of its ad business is a complete reversal for Amazon. In 2009, Bezos famously said “ads are the price you pay for an unremarkable product or service”.

Let's discuss how the pivot went down:

The state of ads on Amazon

Amazon’s original position on ads

The man running Amazon ads

Why Amazon embraced ads

What ads mean for the future of Amazon

The state of ads on Amazon

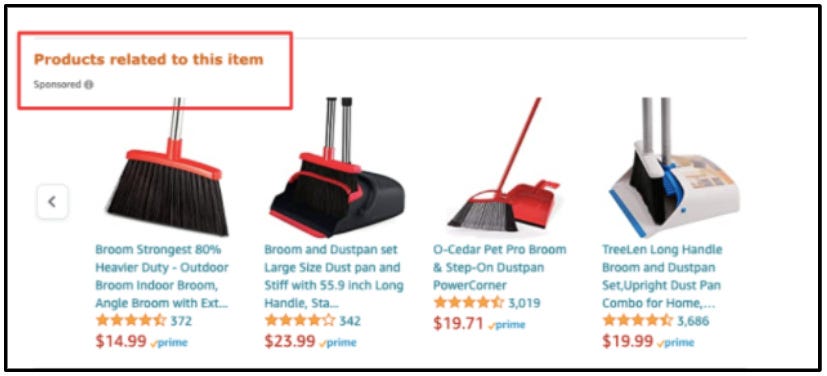

In February 2021, Marketplace Pulse published an article titled “Everything on Amazon is an Ad.” A quick scroll through Amazon confirms the headline:

Search results: On the left is a search for “toothpaste”, with the first 4 results returning sponsored products (depending on the product, the first 3-7 search results can be ads).

Product page: On the right is a product page for speakers. Everything shaded in blue is ad inventory.

The feeling that “everything is an ad” is reflected in Amazon’s earnings, with the ads business currently on an annual run rate of $43B (a significant jump from $1B that Amazon reported as “other revenue” in 2015).

As mentioned in the previous section, Amazon’s ad business is larger than combined sales for Bing, Snap, Twitter/X, Pinterest and TikTok (I used 2022 sales figures — instead of annual run rate — to simplify calculations).

Amazon’s ads have grown so much that — in 2018 — it surpassed Microsoft to become the 3rd biggest digital advertiser. Now, Amazon’s $43B in annual digital ad revenue only trails Alphabet/Google ($200B+) and Meta/Facebook ($110B+).

Amazon’s original position on ads

In 2003, three Amazon researchers published a cornerstone paper for the company: “Amazon.com Recommendations: Item-to-Item Collaborative Filtering.”

For Amazon users, the ultimate e-commerce experience was to be built on a recommendation engine, rather than ads.

Per the paper (bold mine):

At Amazon.com, we use recommendation algorithms to personalize the online store for each customer. The store radically changes based on customer interests, showing programming titles to a software engineer and baby toys to a new mother. The click-through and conversion rates — two important measures of Web-based and email advertising effectiveness — vastly exceed those of untargeted content such as banner advertisements and top-seller lists.

In recent years, Amazon’s organic recommendations…

"Customers who bought this also bought this"

"Customers who viewed this also viewed this"

…have been replaced with ads:

"Sponsored products related to"

"Brands related to this category"

One of the few remaining organic recommendations is the trusty old "frequently bought together" feature.

Sometimes the recommendations make sense…

…and other times, less so:

The man running Amazon ads

On August 22nd, 1994, Jeff Bezos posted the first job listing for Amazon (which was originally called Cadabra; as in abracadabra). The header reads “Well-capitalized Seattle start-up seeks Unix developers”.

Befitting someone that also considered the name “Relentless” for his startup (the relentless.com URL still redirects to Amazon), Bezos is hilariously blunt about the type of colleague he wants:

“You must have experience designing…complex systems…and should be able to do so in about 1/3rd the time that most competent people think is possible”

“Expect talented, motivated, intense and interesting co-workers”

The person running Amazon’s ad business — Paul Kotas — was extremely aware of Bezos’ exacting standards even before Amazon: the two worked together at hedge fund D.E. Shaw in the early 1990s.

Bezos recruited Kotas to Amazon in 1997. Initially, Kotas declined but joined 2 years later after a phone call that probably went something like this:

Bezos: Paul, you gotta come to Amazon.

Kotas: I dunno man. Things were pretty intense the last time we worked together.

Bezos: C’mon. We’re changing the world.

Kotas: Can you be slightly less relentless?

Bezos: No, but I can give you a ludicrous amount of $AMZN stock.1

Kotas: OK, I’m in.

The Information has some great details about the 63-year old Kotas, who is one of the most powerful people in all of digital advertising but flies under-the-radar:

Low key: When he meets with ad execs, Kotas tells his team to identify him as someone who works in “product” (his real title is Senior Vice President and he is part of Amazon’s senior leadership team aka “s-team”). Part of his stealthy approach is to “avoid drawing unnecessary attention” to Amazon’s ad efforts.

Technical background: He’s an “engineer by training” and has ~30 patents under his name. He’s very analytical and “wants arguments backed by data” (kind of like Bezos).

While Bezos hated ads, Amazon has such valuable digital real estate that — in 2005 — he tapped Kotas to explore ways to monetize it.

Per The Information, the first ads were plain vanilla display ads on the product pages. But there was a big problem: competing retailers bid for the ad spots and when users clicked on them, they were taken off the Amazon website.

That first ad project was soon shut down. The next Amazon foray into ads would take a few years and came amidst a rapidly changing tech landscape.

Why Amazon embraced ads

You know the saying “when it rains, it pours”?

That basically describes Jeff Bezos’ angel investing portfolio. In 1998, he cut one of the most baller angel checks ever: Bezos gave two Stanford PhD dudes $250k for their startup.

Those dudes were Sergey Brin and Larry Page.

Here’s how the deal came together per Business Insider (citing Brad Stone’s The Everything Store):

“…the investment story starts with Amazon's 1998 acquisition of Indian delivery service Junglee, which eventually tanked. But the acquisition brought Ram Shriram to the Amazon team, which proved to be a fortuitous meeting for Bezos.

Shriram had been discretely advising two Stanford PhD students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who were trying to invent a new way of searching the internet. In February of 1998, Shriram became one of the first early investors of Google, with a $250k investment.

Six months later, Bezos and his wife were vacationing in the Bay Area when he reached out to Shriram with a request to meet the guys behind Google. Shriram invited the Bezos,' along with Page and Brin, to his house for breakfast with a demonstration of how the search engine would operate. Bezos immediately told Shriram he wanted to invest.

It took some convincing on Shriram's part, since the early funding cycle had closed, but Bezos' status as a CEO with a then $1.6 billion net worth swayed Google's founders to let him in.”

Bezos later said of the deal: “There was no business plan. They had a vision. It was a customer-focused point of view. I just fell in love with Larry and Sergey.”

When Google went public six years later in 2004, Bezos had 3.3m shares of $GOOGL worth ~$285m. He’s since unloaded the stake, which would otherwise be worth ~$10B today. In 2005, he launched his family office — Bezos Expeditions — and has written early checks to Twitter, Uber and Airbnb among others.2

Anyways, I bring this up because Google is the reason that Amazon ultimately went all-in on the ads business.

In the early 2000s, Amazon was becoming too dependent on Google search slots to drive traffic. Per The Information, the company even created an internal “Google Reliance metric” to track this dependence, which — if over-reliant — could become existential.

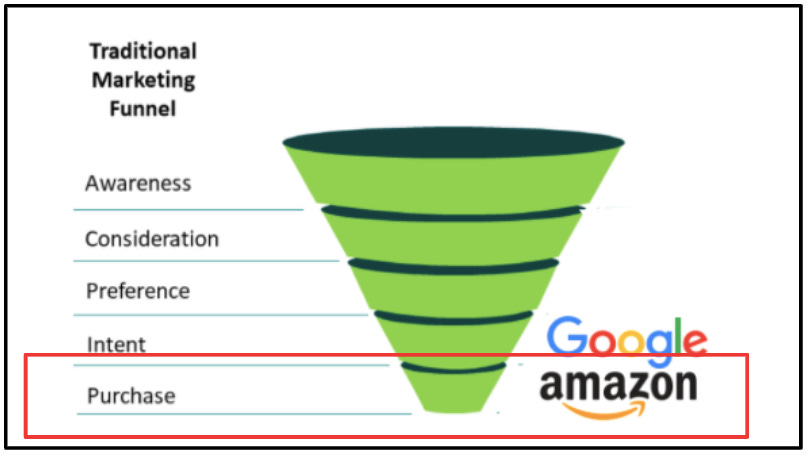

Google, of course, occupies a lucrative part of the customer’s buying journey in the traditional marketing funnel. It sells ads at the point that someone shows intent for a purchase.

However, Amazon owns the last action of the transaction funnel: the purchase itself.

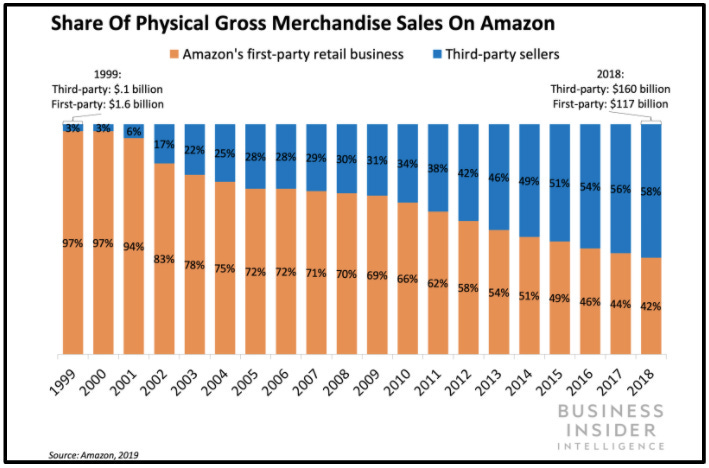

Amazon’s first-party transaction data is particularly valuable for 3rd-party merchants, which have grown from 3% of Amazon sales (2000) to 60% of its $300B+ retail sales (2022).

Separately, more than 63% of all online product searches now start on Amazon and the platform’s 3rd-party merchants are willing to use Amazon’s targeting to put their products in front of customers.

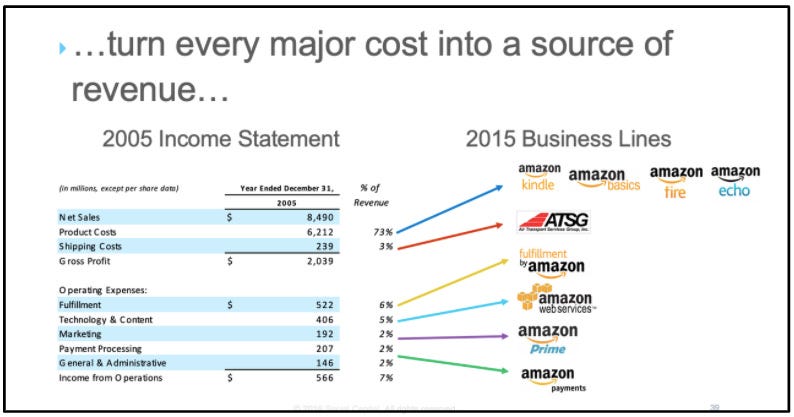

As highlighted by Social Capital in a viral presentation slide, Amazon has a history of methodically turning various expense lines into money makers:

Product costs —> Amazon Kindle, Amazon Basics

Fulfilment costs —> Fulfilment by Amazon

Technology costs —> Amazon Web Services

Marketing costs —> Amazon Prime

Payment costs —> Amazon Payments

Amazon advertising kind of falls into the same bucket because it converts a previous expense (buying Google search ad slots) into a revenue opportunity (selling ad slots on Amazon product searches).

What ads mean for the future of Amazon

Amazon ads might already be the company’s most profitable business line.

Using Google's 68% margin for its core search ad business as a comparison, tech analyst Benedict Evans writes:

"Given [Amazon Ads] margin structure and incremental cost base, it's highly likely to be generating similar absolute profits to [the Amazon Web Services cloud business]."

Napkin math based on Q2 2023 earnings checks out: AWS revenue hit $22B (at a 30% margin, that is $6.6B of operating profit) while Amazon ads hit $10.7B (at 68% margin, that is $7.3B of operating profit).

Clearly, Amazon 3rd-party sellers are wiling to pay for sponsored placements to stand out (just like brands buying eye-level shelf space in grocery stores). And Amazon sells a number of sponsored ad products: search, brand, display, posts and videos.

While Amazon says that ads are “optional”, getting buried on page 5 of Amazon search results is bad for business. The average cost per click (CPC) on Amazon ads is climbing. And it's not uncommon for merchants (there are ~5m on Amazon) to spend up to 50% of a product on listing fees and ads.

While the core e-commerce platform gets more saturated with ads, Amazon is aggressively creating more ad inventory with its video products. Per The Economist, Amazon’s video ads business could be worth $5B within two years:

Prime Video has 150m+ users and — like Disney+ and Netflix — will roll out an ad-tier (**UPDATE: December 27th, 2023: Amazon announced that it will run ads in Prime Video as of January 29th, 2024 and it will introduce a new ad-free tier for $2.99 extra a month).

Its free-streaming service Freevee has 40m users while live-streaming site Twitch has 35m daily visitors

FireTV dongles are in over 100m households

The Seattle-based company is also making a huge play for traditional TV advertising budgets — around $90B a year — by buying up sports media rights. It has a $10B deal with the NFL (over 10 years), is in talks to build out ESPN’s streaming product and will bid on upcoming NBA rights (YouTubeTV and Apple TV+ will throw in bid, too). All of this potential ad inventory is ready-made for the Amazon’s incredibly valuable first-party purchase data.

Costco founder Jim Sinegal once spoke with MIT students about customer obsession. He explained that any savings he negotiated with suppliers were largely passed onto customers.

In one instance, there was such high demand for Calvin Klein jeans that Costco easily could have made extra margin on the pants. But Costco passed on the savings. “Do you know how tempting it was [to raise price]?,” Sinegal said to the students. “But once you do it, it's like taking heroin. You can't stop."

Amazon’s journey into ads is like taking heroin for the business. The margin is so high and the opportunity is so big that the company can’t stop now that its started (even if ads warp the platform’s incentives).

This digital ad pivot is the most successful version of what is becoming a norm due to seismic shifts in the digital ad landscape. In an article titled “Everything is an Ad Network”, mobile tech analyst Eric Seufert explains why it’s attractive for owners of first-party data to build an ads business:

Platform privacy policy decisions such as Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) or Google’s proclamation that it will abandon third-party cookies at some point in the future, in addition to privacy regulation such as GDPR and state-level privacy laws in the US such as CCPA, VCDPA, and ColoPA, are upending many of the fundamental precepts on which digital advertising is predicated. Putting a finer point on it: digital advertising is losing its unfettered, unconsented access to user data and behavioral data emissions. As this foundation of limitless access to user data is challenged and potentially eradicated, the ground beneath the digital advertising ecosystem shifts, and new operating models emerge to capture the attendant inchoate opportunity. One of those new operating models is that everything becomes an ad network. […]

It’s understandable that any company with sufficient size and scale of data would want to build an ad network. Ad networks are highly profitable, generally running on very thick gross margins and mostly monetizing content and product surface area that already exists. So as the norms for data collection and aggregation change, favoring first-party contexts, the companies that can package together their first-party customer data to attract advertising revenue will do just that.

This logic has resulted in a number of retailers and e-commerce platforms embracing ads: Walmart ($2.7B ad sales in 2022), Instacart ($740m in 2022, and a 1/3rd of total revenue), Uber (projected $1B ad sales in 2023).

Other companies with valuable first-party transaction data that have entered the digital advertising game include Shopify, CVS, Target, Walgreens, Lowe's, and DoorDash.

These are all minnows compared to Amazon, though.

Based on current growth trajectories, Amazon ads will keep gaining on Alphabet and Meta (in the latest quarterly earnings periods, Amazon ads grew by 22% compared to 11% for Meta and 3% for Alphabet’s core ad product).

To be sure, Amazon’s ad growth in 2022 ($38B, up +23% YoY) does not match that of Google ($38B in 2011, up +31% YoY) or Facebook ($41B in 2017, up +46% YoY) at similar revenue milestones. However, it is the most credible threat to turn the digital ad duopoly into a tri-opoly (I think that’s a word).

Either way, Amazon ads will keep growing and will continue to have downstream effects on the user experience. Juozas Kaziukėnas from Marketplace Pulse writes that “advertising has distorted Amazon’s customer-obsession" and “clouds the retailer’s ability to innovate on discovery, personalization, and any form of interactive shopping. At a certain point, every decision to improve the experience competes with lost revenue from advertising it would replace.”

That’s pretty depressing. Thankfully, I can drown my sorrows by purchasing some sponsored pressure cookers and toilet seat washlets.

Today’s SatPost is brought to you by Bearly.AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI. And I really like putting blue buttons in this email. If you press this blue button below, you can try AI-powered tools for reading (instant summaries), writing (ChatGPT) and text-to-image art (literally type some text and get a wild image).

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app).

Links and Memes

Here are baller links for you this week:

The history of ketchup: It descends from fish sauce (yes, fish sauce and shoutout Vietnam). The word “ketchup” is a play on the Hokkien word kôechiap, which means “brine of pickled fish”. I explain the full history here (also, check out this wild 5-minute video on the industrial production of Thai fish sauce).

“Only the Passionate Survive”: Nick Maggiulli wrote a great piece about the perils of optimizing his finance blog (Of Dollars and Data) for search. The move increased organic traffic but he hated the content (because it was geared around SEO instead of what he cared about). The approach was leading to burnout, so Nick stopped doing it and is back to writing on topics that he is passionate about.

The mystery of Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders: These athletes were 2-sport stars in the 1990s (both played in the NFL and MLB). Tom Haberstroh and Joe Posnanski explore theories as to why there are no modern-day equivalents of these athletes. A likely explanation: there’s too much money in sports now that if you're good enough to make a professional league, you should play the sport that will pay you the most. Also, these teams paying you a ton don’t want you risking injury in another sport (example: Kansas City Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes isn’t even allowed to play pick-up basketball per his contract).

The Growing Power of IMAX: Matt Belloni at The Town interviews the CEO of IMAX. Despite having less than 1% of all screens, IMAX is responsible for >20% of box office receipts (because blockbusters usually play IMAX). As theatre-goers seek only the best in-person experiences, IMAX is turning into a gatekeeper for Hollywood by deciding which films get the IMAX treatment (Tom Cruise was recently pissed that Oppenheimer got more IMAX screen than the latest Mission Impossible).

Warren Buffett turned 93: The Oracle of Omaha is famous for spending all day reading and only making a few decisions a year. Frederik Gieschen has a great piece about how the fetishization of Buffett’s reading habit hides the fact that he was also a master networker from a young age (“I’m sure Buffett spends a lot of time reading. But always remember that his wealth was built on the balance of compounding wisdom and relationships. In fact, the two reinforced each other. Go and do likewise.”)

…and them fire X posts / tweets:

Ah, so that’s the history of Amazon Prime Day.

And Kotas definitely got a lot of stock. The current CEO of Amazon (Andy Jassy) made a base salary of $160k — which was the max for a corporate employee — when he ran Amazon Web Services (but obviously had a shit ton of stock). Amazon recently bumped the max base salary to $350k.

Good stuff!

One really interesting aspect of Amazon Ads is that a lot of them may come out of "slotting fee" marketing budgets, which may be different than the traditional advertising budgets (say for TV and print).

It's the money that would otherwise be paid at other retailers for better visibility or an endcap placement or a special display unit.