Magnus Carlsen, David Deutsch and the "Fun Criterion"

PLUS: Ferrari’s Wild Economics, Timothée Chalamet, Cost of Being On YouTube.

Thanks for subscribing to SatPost.

Today, we are talking about chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen and how his career relates to David Deutsch’s “fun criterion”.

Also this week:

Ferrari’s Wild Economics

China’s DeepSeek Moment for Films

…and them fire posts (including autocorrect gone wrong)

Norwegian chess legend Magnus Carlsen recently went on the Joe Rogan podcast and the chat is well worth the 2-hour listen.

Carlsen shares a lot about the mindset that made him one of the greatest chess players ever (who provides so many highlights that people make short videos of his checkmate moves that regularly get 10m+ views).

A running theme in the podcast is how Carlsen prioritizes fun and enjoyment while playing chess. He doesn’t treat it like a job at all. In fact, some in the chess community think Carlsen’s training routine is “lazy” compared to best practices:

“The thing is that chess has always been a bit of a hobby for me…once it starts to feel like work, then it's harder for me.”

“I had a chess coach when I was little. I went to sessions once a week, which I loved. Then, he started giving me homework and I told him quickly I don't like homework. But I would still spend a lot of time reading books [and] playing online. Things that I still do but I would do them for fun and that was [the] difference between me and the other kids…they would go to chess practice, they would maybe even do their homework but they weren't living and breathing the game in the way that I was. I think about it all the time.”

“I'm thinking about the game while I'm sitting on this chair [doing this podcast]. I'm still analyzing a game that I played today. It never goes completely out of my mind.”

“I don't necessarily study. I don't deliberately practice all the time. [But] I still process the information.”

“I've always sort of gone my own way [and not followed strict Soviet training methods], tried to have as much fun. Everything has to be about enjoyment.”

“My main motivation for playing chess is that I love to play. I don’t have concrete goals of what I wanted to do, things I want to achieve.”

Rogan commented that Carlsen’s approach shows the difference between obsession and discipline. To be sure, obsession and discipline aren’t mutually exclusive. But Carlsen’s story is about how obsession — and the fun and enjoyment that comes from it — can lead to better results than a more discipline-driven method.

One more interesting nugget from the Rogan interview is that Carlsen’s obsessions was catalyzed because his sister kept beating him in chess:

[I initially] didn't find chess that fun. A couple of years later, my older sister — who is a year and a half older than me — did a lot of chess with my dad. I started sitting in on them a bit and I started liking it. And I really, really wanted to beat my sister as well at generally everything.

The podcast kicked off an interesting conversation on X with user @FallibleMusings posting a clip of Carlsen and adding this note:

Magnus Carlsen gives a great explanation of the extraordinary power of what David Deutsch has coined the “fun criterion”…and the perils of its negation.

Now, before digging into the “fun criterion”, here is some quick background on Deutsch: he is a British physicist and pioneer in quantum computation. He has also written a number of widely-read books in the tech and science communities (“The Fabric of Reality”, “The Beginning of Infinity”) which dive into the topic of epistemology, the field of study about the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge (or the “theory of knowledge” as popularized by philosopher Karl Popper).

Epistemology is an important concept here because Deutsch isn’t thinking of “fun” the way most people see the word. Quick game: if I asked you do some word association with “fun”, what comes to mind? Hanging out with friends? Partying? Watching TV? Dropping molly before a rave at Hakkasan? Playing pick-up hoops? Absolutely destroying the competition on the Rainbow Road course in Mario Kart 64?

These examples are certainly “fun” but they are also fleeting. Too much of any of these activities will turn pleasure or enjoyment into disgust.

Deutsch’s “fun criterion” frames “fun” as more of an emergent property that provides information for decision-making, problem-solving, the creative process and knowledge attainment.

Don’t worry, I will unpack this idea more. But just be warned that the concept is way above my pay grade and even Deutsch admits that we don’t have the language and terms to fully explain the “fun criterion”. It’s a powerful idea, though, and worth exploring.

The analysis is based on two podcasts that Deutsch has done his co-host Lulie Tannett (here and here).

Let’s begin with two statements:

The human experience is complicated: We try to navigate the world with beliefs, emotions and ideas of how the world works. All of these elements interact with each other and often in contradicting ways.

Three ways to express ideas or knowledge:

Explicit ideas can be expressed with ordinary language.

In-explicit ideas can’t be expressed in language but we are aware of their existence.

Unconscious ideas are types of thinking and knowledge creation that are necessary but we don’t even realize that they are happening.

With that context, Deutsch uses the example of a tennis match to explain the difference between the three types of ideas. He doesn’t fully flesh out the comparison but I get the point:

An explicit idea may be when you start a serve and think to yourself “I’m going to put this ball in the back corner of the court” before hitting the ball.

An in-explicit idea may be when your opponent hits the ball back towards you and it looks like it is going out, so you let it pass. However, you don’t actually verbalize “oh, this ball is going to go out” in your mind before taking action. You just let the ball pass you based on instinct and later rationalize the move.

Unconscious ideas are the countless cognitive and physical decisions your body makes without you even realizing. Think about the last time you played tennis or any sport. Can you explain in words what every single muscle fiber or sensory organ was doing at all times? Of course not. But we do know these processes are happening (and praying that we don’t somehow roll our ankles on a random pebble).

According to Deutsch, an important takeaway is that explicit ideas always have large in-explicit and unconscious components. Hitting a tennis ball is never just about the explicit idea of “hey, I’m going to hit this tennis ball”. It is everything happening underneath the surface of what we can actually verbalize and think of in real-time.

Also, what your conscious mind tells you may contradict what your unconscious muscle-memory wants you to do (eg. listen to an interview with any top-tier athlete and it’s clear that many of their actions are drilled into them from 1000s of hours of practice and the actions are instinctive rather than conscious; they hate “overthinking it”).

“A common criterion [for decision-making],” says Deutsch, “is to try to disregard everything but your explicit [ideas].”

In other words: people are over-indexing on explicit ideas — things they can verbalize, write down or rationalize — relative to in-explicit ideas or unconscious ideas.

This is where “fun” comes into play. It’s a feeling that helps to resolve potential contradictions between explicit, in-explicit and unconscious ideas. You may not be able to put words on why or how but that feeling is telling you something. It can be a factor to inform your decision-making or the spark of creativity to help solve a problem.

In Deutsch’s view, “fun” is an emergent property that a person experiences from doing an activity. It is a type of information or knowledge. The lack of “fun” can also be as informative as the presence of “fun”.

“If something you are doing or proposed to do isn't fun,” says Deutsch. “Then there's something unsolved. There is something that has to be answered.”

That answer can better help put our actions into alignment with what we actually want to achieve.

But why should we listen to our in-explicit or unconscious ideas? The great American writer Cormac McCarthy has one potential answer and it has to do with evolution. In a mind-bending essay for Nautilus in 2017 (“The Kekulé Problem”), McCarthy makes the argument that the unconscious mind is much more developed and innate to humans than language (which is comparable to Deutsch “explicit ideas” concept).

The earliest form of language (graphics in South African caves) is maybe 100,000 years old. Meanwhile, homo sapiens are part of the hominid species and that lineage goes back 2 millions years. The unconscious mind — which McCarthy pithily describes as “a machine for operating an animal” — has been there since the beginning:

One hundred thousand years is pretty much an eyeblink [in history]. But two million years is not. This is, rather loosely, the length of time in which our unconscious has been organizing and directing our lives. And without language you will note. At least for all but that recent blink. How does it tell us where and when to scratch? We don’t know. We just know that it’s good at it. But the fact that the unconscious prefers avoiding verbal instructions pretty much altogether—even where they would appear to be quite useful—suggests rather strongly that it doesn’t much like language and even that it doesn’t trust it. And why is that? How about for the good and sufficient reason that it has been getting along quite well without it for a couple of million years?

McCarthy then talks about the development of language:

The invention of language was understood at once to be incredibly useful. Again, it seems to have spread through the species almost instantaneously. The immediate problem would seem to have been that there were more things to name than sounds to name them with. Language appears to have originated in southwestern Africa and it may even be that the clicks in the Khoisan languages—to include Sandawe and Hadza—are an atavistic remnant of addressing this need for a greater variety of sounds. The vocal problems were eventually handled evolutionarily—and apparently in fairly short order—by turning our throat over largely to the manufacture of speech. Not without cost, as it turns out. The larynx has moved down in the throat in such a way as to make us as a species highly vulnerable to choking on our food—a not uncommon cause of death. It’s also left us as the only mammal incapable of swallowing and vocalizing at the same time.

The sort of isolation that gave us tall and short and light and dark and other variations in our species was no protection against the advance of language. It crossed mountains and oceans as if they weren’t there. Did it meet some need? No. The other five thousand plus mammals among us do fine without it. But useful? Oh yes.

Evolutionarily, we didn’t need language to survive. This isn’t to say that it served no purpose. It seems pretty necessary to co-ordinate large groups and build knowledge to sustain large populations. But purely for individual survival: did we ever need it? Thousands of other mammals have persisted without it.

Conversely, the unconscious mind was clearly needed from the get-go. It has helped the homo species survive and adapt for millions of years. How does it work? We don’t fully know but McCarthy points to dreams as one pathway for the unconscious mind to operate.

OK, so I’m way over my skis right now but let me tie McCarthy’s article to Deutsch’s “fun criterion”. If the emergence of “fun” is due to our explicit ideas interacting with our in-explicit and unconscious processes, we should be much more attuned to those feelings. “Fun” is information to help us solve problems or make decisions. The emergent feeling of “fun” is telling us that our different sense-making processes are aligned. The existence of this feeling means a person doesn’t have to rely as much on “discipline” or external coercion to keep going down a chosen path because there’s less tension between the explicit, in-explicit and unconscious. This situation also means that one can pursue such an activity for a long time and obsess over it to yield the benefits of compounding. It’s the difference of Carlsen thinking of chess all the time vs. another successful player just studying the game in pre-defined blocks of time.

Deutsch’s “fun” seems related to idea of flow, the feeling of being dialled in on a single task. Being in the zone when time flies. The feeling of flow is also information. It isn’t the only information you consider, though. A person can be in flow writing a novel, running a marathon, coding up a storm or playing slots for 10 hours. However, the feeling after each of these activities won’t all be the same. You’ll probably be happy with the first three examples of flow but deeply regret the double-digit hour gambling sessions.

As with “fun”, flow is information to help you decide if this is the right activity. Drinking may be enjoyable in the moment but feel awful the next morning. The decision to do it next time needs to take all of that into account.

At this point, you’re probably thinking one of 4 things:

“Wow, Trung just spent 500 words to say ‘trust your gut!’”

“Holy cow, Trung discovered that fun and enjoyment help people do good work and are important for hobbies.”

“Trung just discovered the difference between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation.”

“Bro, sounds like Ikigai to me.”

The reason I know you’re thinking this is because those were some of the comments in the @FallibleMusing post that I highlighted earlier.

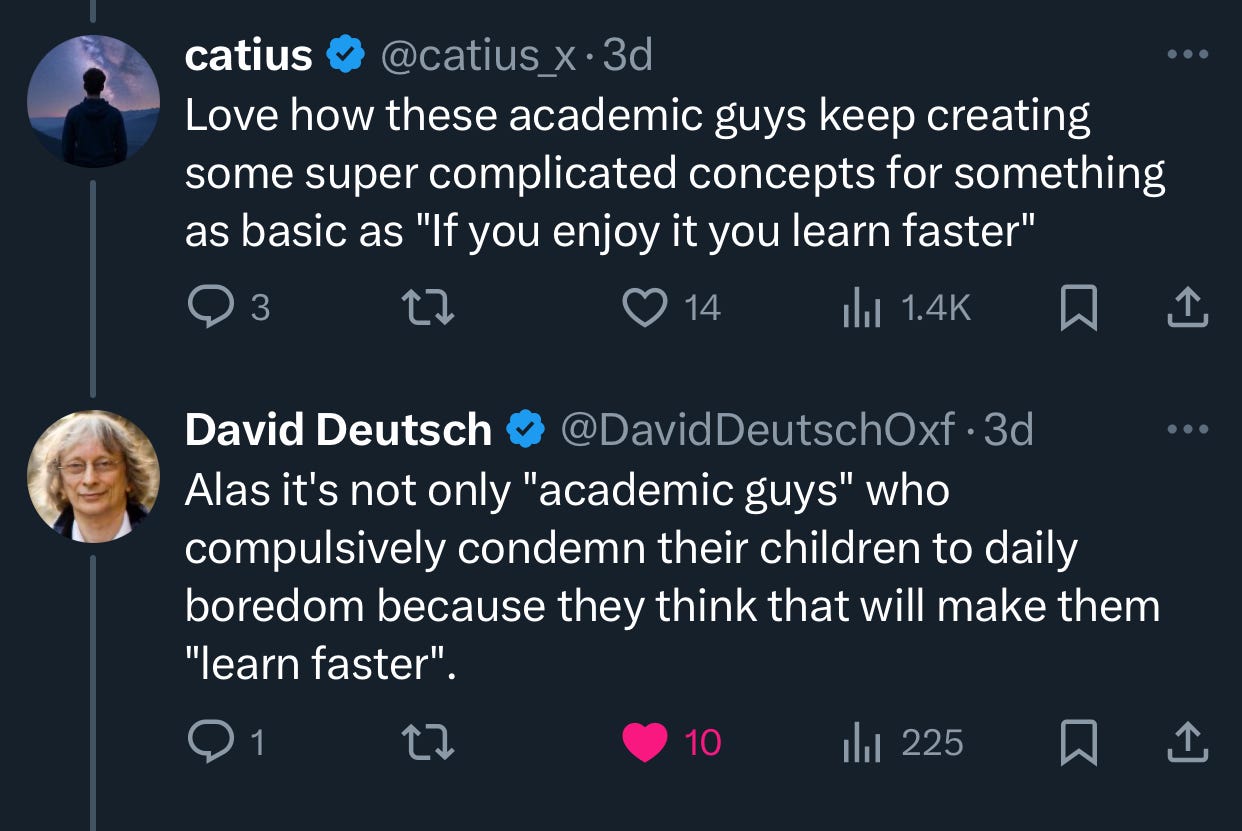

Deutsch himself replied to one troll:

I’m with Deutsch here. The knee-jerk reaction to the “fun criterion” seems to be that it’s an obvious idea. But even with this simple framing, there are a lot (a lot) of people that don’t live their lives with “fun” as a type of information to help make decisions.

I know because I’m one of those people. I spent a decade in the corporate world (tech, finance) rationalizing a job that didn’t create any “fun”. I’m not talking about the “follow your passion” BS. I literally just mean I spent over 10 years not even including the feeling of “fun” into my professional forays.

Rather, these were my main concerns: What is the salary? Will this look good on my CV? Will this raise my status amongst my friends? Will this make my parents happy? What are the most sought after roles (aka Mimetics 101)? What are the hours? Is there work-life balance? Does society value this role? How far is the commute? Do they have La Croix Lemon bubbly water?

For sure, all of these are important questions. But, alas, I had zero consideration of the “fun criterion”. Unsurprisingly, I found the corporate office job completely soul-sucking and hated every second of it. I hate spreadsheets. I don’t want to model finances. I don’t want to pivot the tables. Also, do you know how dumb I look in Brooks Brothers dress pants? Despite these feelings, I kept doing these type of roles. Looking back, it was valuable to try different careers but persisting in them when I didn’t enjoy them at all was negating the “fun criterion”.

In parallel to this corporate life, I spent more than a decade trying to break into Hollywood. I co-wrote and sold a comedy film script to Fox but never turned it into a real gig. If you take took the option fee I was paid and divided it by the number of hours I put into the project, the hourly wage would be in the range of $0.87 to $1.69. Still, the emergent fun and enjoyment from the experience was telling me something. I obviously wanted to write and share ideas and make people laugh (eg. the film's logline is "Harold & Kumar meets The Fugitive, set in Southeast Asia" and a dildo-shaped knife featured prominently in the first draft of the script). However, the corporate world wasn’t the correct path. I have now designed a life to read and write and publish whatever I want but could have landed on this path years earlier if I had factored in the “fun criterion”.

Following the “fun” will be different for everyone.

Te first step is just to be aware of its existence.

Back to Carlsen. He is obviously extreme extreme outlier. Very few chess enthusiasts will ever be able to make a career out of this hobby the way Carlsen has done.

Still, Carlsen’s path to the top of the game is an instructive example of the “fun criterion” at work. He didn’t follow the prescribed path for chess grandmasters including the homework assigned by his first chess teacher or the Soviet training method.

Carlsen embraced the “fun”, “play” and “enjoyment” in his chess journey. This approach almost certainly led to creative chess moves that helped him beat opponents (random side note: to keep his mind fresh, he often watches 30 minutes of NBA highlights before a chess match).

A quote from Swiss psychologist Carl Jung helps to explain why this mindset works: “The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with the objects it loves.”

There’s a really insightful Reddit comment that further explains Jung’s quote and has parallels to Deutsch’s “fun criterion”:

Play is both investment in an outcome and being open to the possibility of different outcomes. These outcomes can't be so bad as to jeopardise one's survival, otherwise they are no longer play but matters of 'real life,' but it's clear that there's an element of game theory and probability at work.

In short, the creative mind 'plays' with its object - that is, opens it up to different possibilities as an exploratory venture. This can't be the realm of intellect, which is about categorising what is already known. Unlike intellectual exercise, play requires a priori investment, an element of faith before the fact, a commitment before the result can be proven. This act of faith in an environment that is otherwise uncertain allows for the manifestation of unexpected outcomes, i.e. creativity.

Notably this is an unconscious and emergent property of acting with commitment in an otherwise variable and indeterminate system. It is dependent on faith without the fact, which is an unconscious act and therefore not intellectual or rational.

If a random Redditor doesn’t do it for you, then how about a random physicist with a tremendous moustache named Albert Einstein: “Play is the highest form of research.”

Remember, Carlsen says chess is “a bit of a hobby” because “once it starts to feel like work, then it's harder”.

While maybe not disciplined in a traditional manner, Carlsen found enjoyment in being obsessed with the game and achieved some stunning results (although, I should add that "winning" as a goal may not always align with "fun"; someone could play chess moves in a "fun" way that might not necessarily be the most game optimal decision).

How about the reverse of Carlsen? Getting to the top of a profession with strict discipline and negating the “fun criterion”. Conveniently for this article, there’s actually a famous tennis example: Andre Agassi. The American tennis champion started playing at 3. This wasn’t a voluntary decision, though. His father — who competed for Iran in the Olympics for boxing and was a tennis coach — decided he would turn Andre into a tennis prodigy.

In his autobiography Open, Andre explained his childhood training regimen:

My father says that if I hit 2,500 balls each day, I’ll hit 17,500 balls each week, and at the end of one year I’ll have hit nearly one million balls. He believes in math. Numbers, he says, don’t lie. A child who hits one million balls each year will be unbeatable.

The elder Agassi built a special machine called “The Dragon” to shoot the balls at Andre, who never actually chose to play the sport. It did work. Agassi turned pro at 16 and won 8 Grand Slam tournaments during a career that lasted 20 years.

However, after retiring, Agassi said that he hated tennis with “a dark and secret passion.” He said his father’s training bordered on child abuse. The mental anguish was reflected in Agassi’s career with on-court outbursts and a substance abuse problem.

It is certainly possible to achieve in a field without consideration of “fun”. But all things equal, doing work or pursuing a hobby with the consideration of “fun” seems much more optimal (mentally, physically and spiritually).

Another tennis legend (probably the GOAT) Novak Djokovic had to find joy in the game before going on his epic run in the 2010s…as explained by Billy Oppenheimer:

Days after a quarterfinals loss in the 2010 French Open, Novak Djokovic told his coach, Marián Vajda, that he had decided to quit playing tennis. He was No. 3 in the world, a grand slam winner, and a favorite to win Wimbledon. After Djokovic said he was quitting, Vajda asked, “Why did you start playing this sport?” Vajda immediately sensed what the problem was: Djokovic was focusing too much on rankings, records, titles, and external expectations. As a result, Djokovic said, “I was mentally at one very messed up place.”

As Djokovic thought about Vajda’s question, he thought about how many of his earliest childhood memories include his “most beloved toy”—a mini tennis racket and a soft foam ball. He started playing tennis, answering Vajda’s question, “because I just really loved holding that racket in my hand.” “Do you still love holding a racket in your hand?” Vajda asked. Djokovic thought about it for a few seconds, got excited, and said: “I do. I still love holding a racket in my hand. Whether it’s a grand slam final on center court or just playing around on a public court, I like playing for the sake of playing.” Vajda nodded, “Well that’s your source.

That’s what you need to tap into. Put aside rankings and what you want to achieve and what you think others are expecting of you.” Vajda then suggested that Djokovic take a few weeks off. Djokovic agreed that he would. But when he woke up the next morning, Djokovic was dying to hit tennis balls. He went to the courts to play for the sake of playing. “And I never looked back ever since that moment.” The following season, Djokovic enjoyed one of the greatest seasons in sports history. He won 43 straight matches. He won three Grand Slams, including his first Wimbledon title. And he finished the year as the number one player in the world. “I started to play freely,” he says of that season. “I became the kid that I was when I started playing.” Years later, he’d say, “I can carry on playing at this level because I like hitting the tennis ball.”

Look, I know a lot of this still must feel nebulous and wishy-washy. Don’t blame Deutsch. I’m not doing his work justice. To wrap up, the best I can offer are quotes from notable individuals that share similarities to the “fun criterion”:

Steve Jobs: "Have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become."

Richard Bach: "The more I want to get something done, the less I call it work."

Naval Ravikant: “What feels like play to you, but looks like work to others?” (PS. Check out Naval’s three-person podcast episode with Tim Ferriss and David Deutsch).

Warren Buffett: “I truly do feel like tap dancing to work every day.”

Derek Sivers: “If you’re not feeling ‘Hell yeah, that would be awesome!’ about something, say no.”

Oprah Winfrey: "Passion is energy. Feel the power that comes from focusing on what excites you.”

My son: Literally every single one of his new obsessions blows me away. Dinosaurs. Race cars. Penguins. Donut makers. Tae-kwon do. His “fun” criterion radar is very very strong right now (and I feel strongly that one of my jobs as a parent is to make sure he keeps it that way; Deutsch has another saying that seems relevant, "take children seriously").

Claude Shannon: “I was motivated more by curiosity. I was never motivated by the desire for money, financial gain. I wasn’t trying to do something big so that I could get a bigger salary.”

Jony Ive: “My intuition is an incredibly dominant part of how I look at the world and how I think. Even when I think rationally, I pay attention to how I feel.”

Ray Bradbury: “Don’t think. Thinking is the enemy of creativity. It's self-conscious, and anything self-conscious is lousy. You can’t try to do things. You simply must do things."

Richard Feynman: “If you're not having fun, you're not learning. There's a pleasure in finding things out.”

Hopefully, one of those quotes helped to unlock Deutsch’s idea and will help you find a way to follow your fun (…or just watch Carlsen following his fun while beating 10 people at chess at the same time while blindfolded).

Ferrari’s Wild Economics

The luxury industry has hugely benefitted from the rise of the Chinese consumer.

Case in point: China now accounts for ~1/5th of all LVMH sales.

A random and extremely niche side effect of this trend is that me (Trung Phan, Vietnamese guy) can walk into any luxury store in the world with flip flops, hoodie, basketball shorts and a backwards turquoise Vancouver Grizzlies hat and get A+ service.

Employees at Hermes, Tiffany’s or Rolex dealers have no idea whether or not I’m a Chinese billionaire (spoiler alert: I’m neither the adjective nor the noun) so they give the white-glove treatment for at least 8 minutes before getting suspicious.

However, there is one brand that always quickly sniffs out my ruse: Ferrari. The luxury carmaker gate-keeps its vehicles so well that I definitely need a referral from a Ferrari owner to be taken seriously. And no self-respecting Ferrari owner — even some of my friends — would be foolish enough to sully their name by referring Trung Phan (Vietnamese guy, who sometimes is mistaken for a Chinese billionaire at Dior in Paris).

Anyway, that is a long pre-amble for an interesting article I read via The Wall Street Journal titled “The Wild Economics Behind Ferrari’s Domination of the Luxury Car Market”.

I had no idea but the legendary Italian brand is now Europe’s top carmaker. Well, actually, it’s not an automaker according to the company’s CEO Benedetto Vigna, “[Ferrari] is not an automotive company…it is a luxury company that is also doing cars.”

Here are some other interesting facts about this “luxury company that is also doing cars":

Since its IPO in 2015, Ferrari's market cap has increased ~10x to $90B+.

In 2024, it only sold 13,752 vehicles for $6.7B (average of ~$490k a car).

The luxury positioning is why Ferrari has a 28% operating margin while Volkswagen has an operating margin of 4% (VW sold 9 million vehicles in 2024 and its market cap is less than half of Ferrari: ~$40B).

German carmaker Porsche IPO'd in 2022 and tried a similar luxury playbook but is down 1/3rd since then, to a market cap of $55B; it sells way too many cars relative to Ferrari (310,718 in 2024) and is having difficulty transitioning to EVs.

As with any luxury brand (the CEO compares itself to Hermes) Ferrari tightly controls supply based on this saying from founder Enzo Ferrari: "Ferrari will always deliver one car less than the market demands.”

Ferrari restricts who can buy its vehicles with waiting lists and prioritizes existing owners (owners refer new owners — spoiler alert: not me — to get on the buying ladder).

The top models such as LaFerrari (F80 and Enzo beforehand) are now reserved for customers that own multiple vehicles, bought one in the past 3 years and are active in the Ferrari community ("the algorithm has grown more sophisticated...to include the events customers attend, whether they take part in Ferrari’s racing program, whether they have had heritage models restored in its classic-car workshop, and many other variables".)

This luxury set-up means many Ferrari cars keep increasing in value (a well-preserved LaFerrari can sell for $3.8m on secondary markets). On that note, if you see the hat below at a used-Ferrari car auction, come say “hi”.

PS. Check out my article on Hermes and how it “creates desire” by “selling time”.

This issue is brought to you by Bearly AI

Why are you seeing this ad?

Because I’m trying to learn the ways of Hermes and sell “desire” but haven’t fully figured how to do that yet.

In the meanwhile, I co-founded an AI-powered research app called Bearly AI that can save you and your team hours of work. We just added two new powerful models from Anthropic (Sonnet 3.7) and OpenAI (GPT 4.5) for coding, reading and writing. You can try those along with image, text and audio models from DeepSeek, Grok, Whisper, Gemini, Stable Diffusion and more.

It’s all available in one keyboard shortcut (and an iPhone app). Use code BEARLY1 for a FREE month of the Pro Plan.

China’s DeepSeek Film Moment?

A few weeks ago, we talked about the Chinese AI startup DeepSeek and how its efficiency breakthroughs shook up the entire tech industry.

DeepSeek was the latest in a decade of Chinese companies breaking through in global markets across various consumer industries: TikTok (social media), BYD (electric cars), Huawei (phones), Shein and Temu (e-commerce), Mixue (tea shop) etc.

Last year, a Chinese game developer made the first triple-A smash hit global game (Black Myth: Wukong).

One cultural export that has really eluded China is film. The country has released domestic blockbusters but nothing has really broken though internationally.

That may have changed with Ne Zha 2, a sequel to 2019’s “Ne Zha” that tells the story (inspired by a 16th century Chinese novel) of a boy with god-like powers who saves his village.

It’s on pace to gross $2B and is already the highest grossing animated film ever. That figure tops previous leaders including Inside Out 2 ($1.7B), Frozen 2 ($1.5B) and The Super Mario Bros. Movie ($1.4B).

It took 5 years to make and co-ordinated 4,000 people across 130+ animation studios in China. While the original film Ne Zha made $740m (mostly in China) on a budget of ~$20m. The success bumped the sequel’s budget to $80m and it’s blown past expectations and set numerous box office records:

Highest grossest China film ($1.5B+)

Highest grossest non-English film ever

Highest take in a single country (beating Star Wars: The Force Awakens gross of $965m in America in 2015)

Too lazy to inflation adjust (don’t yell at me) but Ne Zha 2 will join the exclusive 2 Billy Box Office Club: Avatar ($2.9B), Avengers: End Game ($2.8B), Avatar: The Way of Water ($2.3B), Titanic ($2.2B), Star Wars: The Force Awakens ($2.1B) and Avengers: Infinity War ($2.0B).

The film’s 45-year old director Yang Yu (who goes by “Jiao Zi”, which translates to dumpling) has an awesome backstory. He studied to be a pharmacist in university but when he graduated in 2005, didn’t want to enter the field. Jiao Zi was obsessed with animation and taught himself how to do the trade, per SCMP.

But without a job, he lived at home and on his mom’s monthly pension of <$200 for 4 years…until he made a 16-minute short film in 2009 that garnered attention.

A lot of this backstory is reflected in the Ne Zha series.

The majority of Ne Zha 2’s box office is in China but $15m in America isn’t bad and China’s animation industry — which has been the workhorse for Korean and Japanese animated films — has proven that it can take Chinese IP abroad. The country has a very rich tradition to draw from and I wouldn’t be surprised if we look back at China’s film industry in 20-30 years and note Ne Zha 2 as a gamechanger.

Links and Memes

Timothée Chalamet (aka the hottest actor in the game) was in the news last week for giving a very baller acceptance speech for a Best Actor award he received for his role as Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown. Amazingly, Chalamet just came out and said he worked hard AF in the role and wants to be great:

“I know we're in a subjective business, but the truth is, I'm really in pursuit of greatness. I know people don't usually talk like that, but I want to be one of the greats."

He cited actors (Daniel Day-Lewis) and athletes (Michael Jordan) as inspirations.

Fantastic. He’s dialled in. No apologies.

Love his backstory: Chalamet saw Heath Ledger in The Dark Knight in 2008 and — at the age of 13 — decided he wanted to be an actor. Asked his parents to transfer him to a arts-focussed high school then caught his first film break when Christopher Nolan plucked him from auditions to play Matthew McConaughey’s son in Interstellar (2014). How wild is that? The guy that made the film that inspired you to do the thing ends up picking you up to help your career along.

Now, he’s been on the grind for 15 years+ and is definitely the IT young actor. Good for him. Get it bruh!

As a quick aside, I consumed so much Bob Dylan content in the past few months because of Chalamet’s new film. Haven’t even seen it but happy I went down the rabbit hole because I discovered this tribute that Dylan wrote to Johnny Cash for Rolling Stone magazine in 2003.

“I was asked to give a statement on Johnny’s passing and thought about writing a piece instead called “Cash Is King,” because that is the way I really feel. In plain terms, Johnny was and is the North Star; you could guide your ship by him — the greatest of the greats then and now. I first met him in ’62 or ’63 and saw him a lot in those years. Not so much recently, but in some kind of way he was with me more than people I see every day.

There wasn’t much music media in the early Sixties, and Sing Out! was the magazine covering all things folk in character. The editors had published a letter chastising me for the direction my music was going. Johnny wrote the magazine back an open letter telling the editors to shut up and let me sing, that I knew what I was doing. This was before I had ever met him, and the letter meant the world to me. I’ve kept the magazine to this day.

Of course, I knew of him before he ever heard of me. In ’55 or ’56, “I Walk the Line” played all summer on the radio, and it was different than anything else you had ever heard. The record sounded like a voice from the middle of the earth. It was so powerful and moving. It was profound, and so was the tone of it, every line; deep and rich, awesome and mysterious all at once. “I Walk the Line” had a monumental presence and a certain type of majesty that was humbling. Even a simple line like “I find it very, very easy to be true” can take your measure. We can remember that and see how far we fall short of it.

Johnny wrote thousands of lines like that. Truly he is what the land and country is all about, the heart and soul of it personified and what it means to be here; and he said it all in plain English. I think we can have recollections of him, but we can’t define him any more than we can define a fountain of truth, light and beauty. If we want to know what it means to be mortal, we need look no further than the Man in Black. Blessed with a profound imagination, he used the gift to express all the various lost causes of the human soul. This is a miraculous and humbling thing. Listen to him, and he always brings you to your senses. He rises high above all, and he’ll never die or be forgotten, even by persons not born yet — especially those persons — and that is forever.”

***

Some other links for your weekend consumption:

Two AI agents were chatting and realized they were AI agents and decided to communicate in a different soundwave because it was more efficient. Just wild and things are about to get weird. (X/Georgi Gerganov)

The True Costs of Being on YouTube…You may know Chef Carla Lalli Music from the Bon Appétit test kitchen. She spent the past 4 years going solo on YouTube but found the platform economics unworkable. She was spending $14k a month on the cooking videos but only getting $4k a month in ad revenue. A major issue is that she was paying a whole production team but getting the same views as solo creators that only use their smartphone. To make high-production costs work on YouTube, you really have to have scale and her videos were averaging under 50,000 views. (Food Processing)

A wild startup pitch…Optifye — a startup that monitors factory workers — released a pretty absurd demo video. I mean, every industry has some form of workplace monitoring but this pitch was giving “late 1990s Vietnamese Nike sweatshop” vibes. (X/Litquidity)

Francis Ford Coppola…the legendary director’s Megalopolis was nominated for a Razzie for worst film of 2024…and he took it in stride with a great post including this line about making the film “at a time when so few have the courage to go against the prevailing trends of contemporary moviemaking!” (Instagram/Francis Ford Coppola)

RIP Gene Hackman…the also legendary actor — who starred in Coppola’s 1974 film The Conversation (and other classics including The French Connection, Unforgiven, The Royal Tenenbaum) — was found dead at 95 along with his wife Betsy Arakawa in what looks like an accident in their home. Tribute from Hollywood and three things I’ll flag are: 1) great Hackman story from Kevin Costner; 2) my favourite scene in Unforgiven; 3) and the amazing confrontation with Denzel in Crimson Tide.

Deep Research…the AI tool from OpenAI that can pump out McKinsey-calibre reports on any topic in minutes is quite powerful. However, Benedict Evans writes that while impressive, it is still only 80-90% correct and the way generative AI works means that it may not ever get to 100% and that greatly diminishes the tool’s value. (Benedict Evans)

A very good subreddit…called “r/thatsabooklight, where people point out the mundane origins of movie props”. (X/Visakan Veerasamy)

Dating apps..are going to get completely cooked by AI chatbots. (X/BachelorJoker)

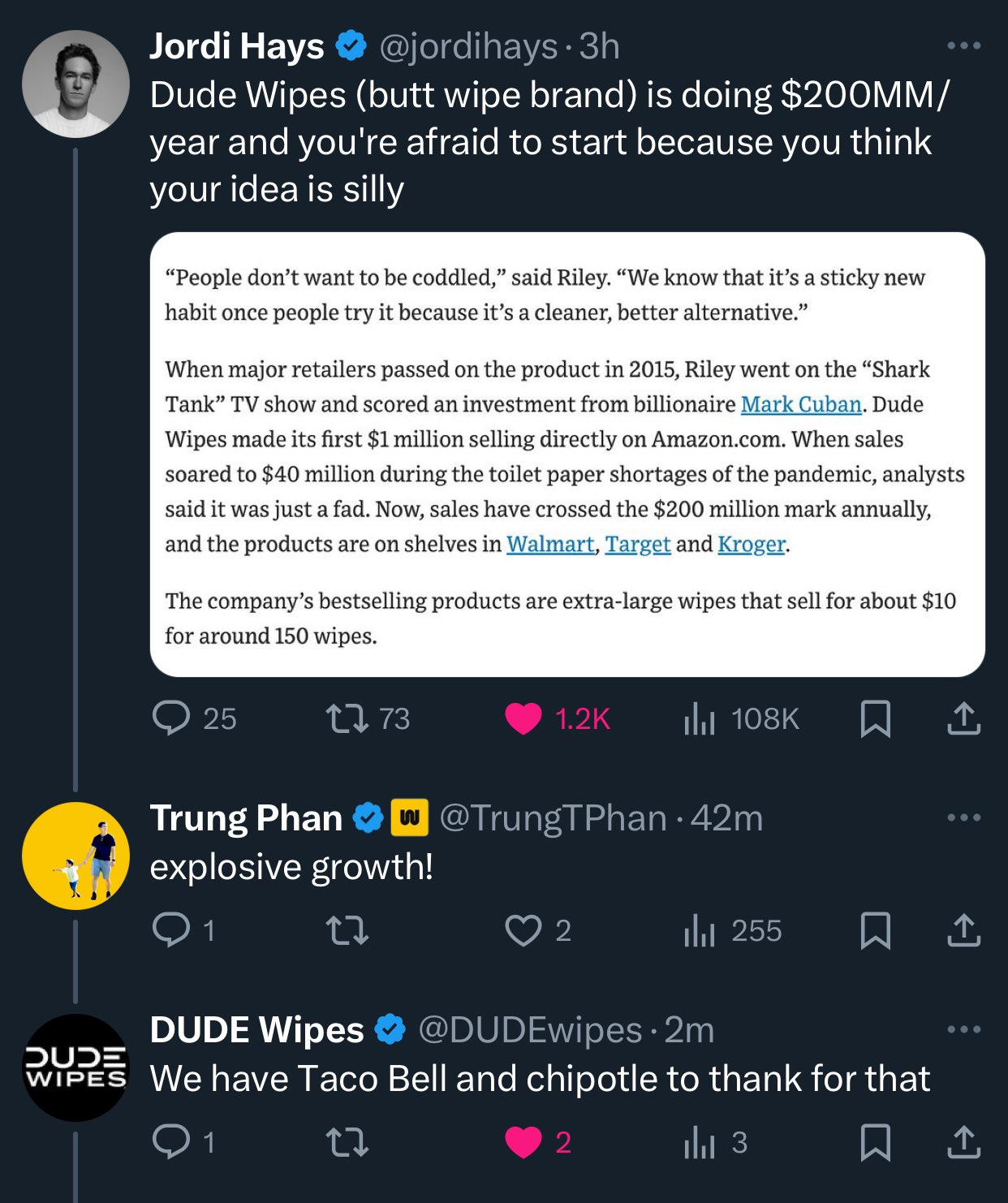

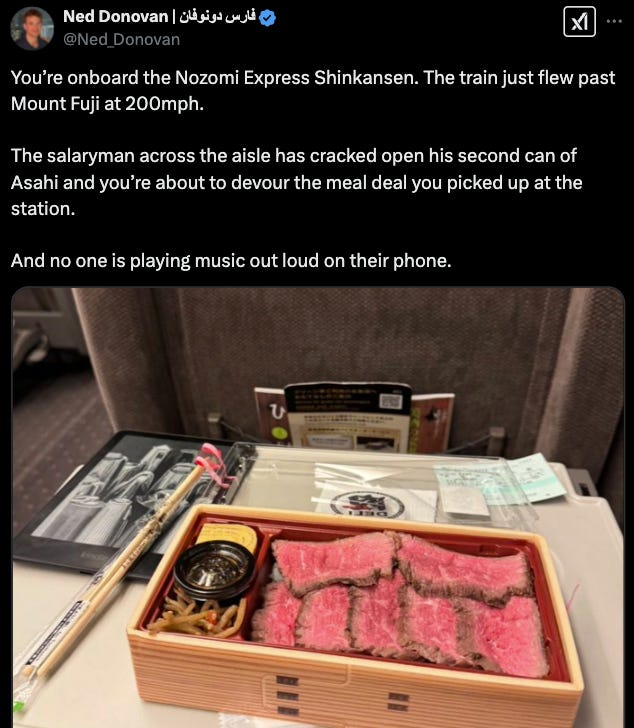

…and them fire posts (including a reminder that everytime you see an Apple Intelligence gaffe, just remember that iPhone autocorrect has been one of the most dismal applications of AI in the past decade):

Excellent. Really. Thank-you.

Cheers,

ME

Pursuing your fun, passion, whatever you call it, is great until it starts hurting others, see F-Elon and Bezos (perpetuating misinformation through the press).